By the 9th century, in an inextricable organic connection with the design of buildings, a system of their internal decorative decoration was taking shape. One of the major figures of the Byzantine church, Patriarch Photius, devoted one of his homilies (conversations) to a description of the mosaics that decorated the palace church of Nea Basilia, dedicated to the Mother of God (mid-9th century). In this church, in the dome, Christ the Pantocrator (almighty) was depicted, surrounded by angels, in in the apse there was the Mother of God Oranta, then on the vaults were the apostles, martyrs, prophets, etc.

The strict system of arrangement of images in architecture gradually acquired canonical forms and to a certain extent reflected the earthly feudal hierarchy.

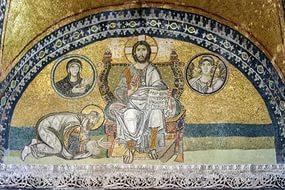

Mosaics of the Church of St. Sofia. The culture of Byzantium emerged from antiquity and continued to maintain connections with it. This is especially noticeable in the art of the Constantinople school in the first decades after the restoration of icon veneration. The mosaics of the Church of St., discovered in the 30s of our century. Sofia gives an idea of the development of metropolitan art ranging from the mid-9th century to the mid-12th century. The earliest (located in the altar) images of the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin and Child preserve Hellenistic traditions, reminiscent of Nicene mosaics.

Despite the earthly nature of these images, they are distinguished by deep spirituality. Here the free manner of contrasting juxtaposition of multi-colored smalt cubes is still preserved, but later the mosaics are laid out in more regular rows with gradual transitions of cubes that are similar in tone.

Above the main door leading from the narthex to the temple is the Emperor Leo the Wise, prostrate before the throne of Christ. The scene recalls the ceremonies of the Byzantine court, described in detail in the work of the Byzantine emperor Constantine Porphyrogenitus. The face of Emperor Leo is portrait. Heavy folds of rich clothes follow the position of the figure, but in the laying of cubes there is a noticeable strengthening of the linear principle.

Similar scenes of offering subsequently became widespread in the art of Byzantium and related countries.

In the southern gallery of the temple, a whole series of imperial portraits from the 11th and 12th centuries has been cleared away. There is a lot of convention in them with great attention to the transfer of various details of lush multi-colored clothes. However, in later parts of the mosaics of St. Sofia's faces do not lose volumetric modeling, her figures retain the correct proportions. The faces of the Mother of God and John the Baptist in the composition of the deesis (deesis in Greek - scene of prayer) of the mid-12th century are full of deep spirituality.

The noble aristocracy of the face of Christ in the same composition is far from the severe severity of the Pantocrator (Pantocrator) of the provincial monuments of the same time; all these faces are conveyed with soft plasticity. Miniature 9-10 centuries.

The noble aristocracy of the face of Christ in the same composition is far from the severe severity of the Pantocrator (Pantocrator) of the provincial monuments of the same time; all these faces are conveyed with soft plasticity. Miniature 9-10 centuries.

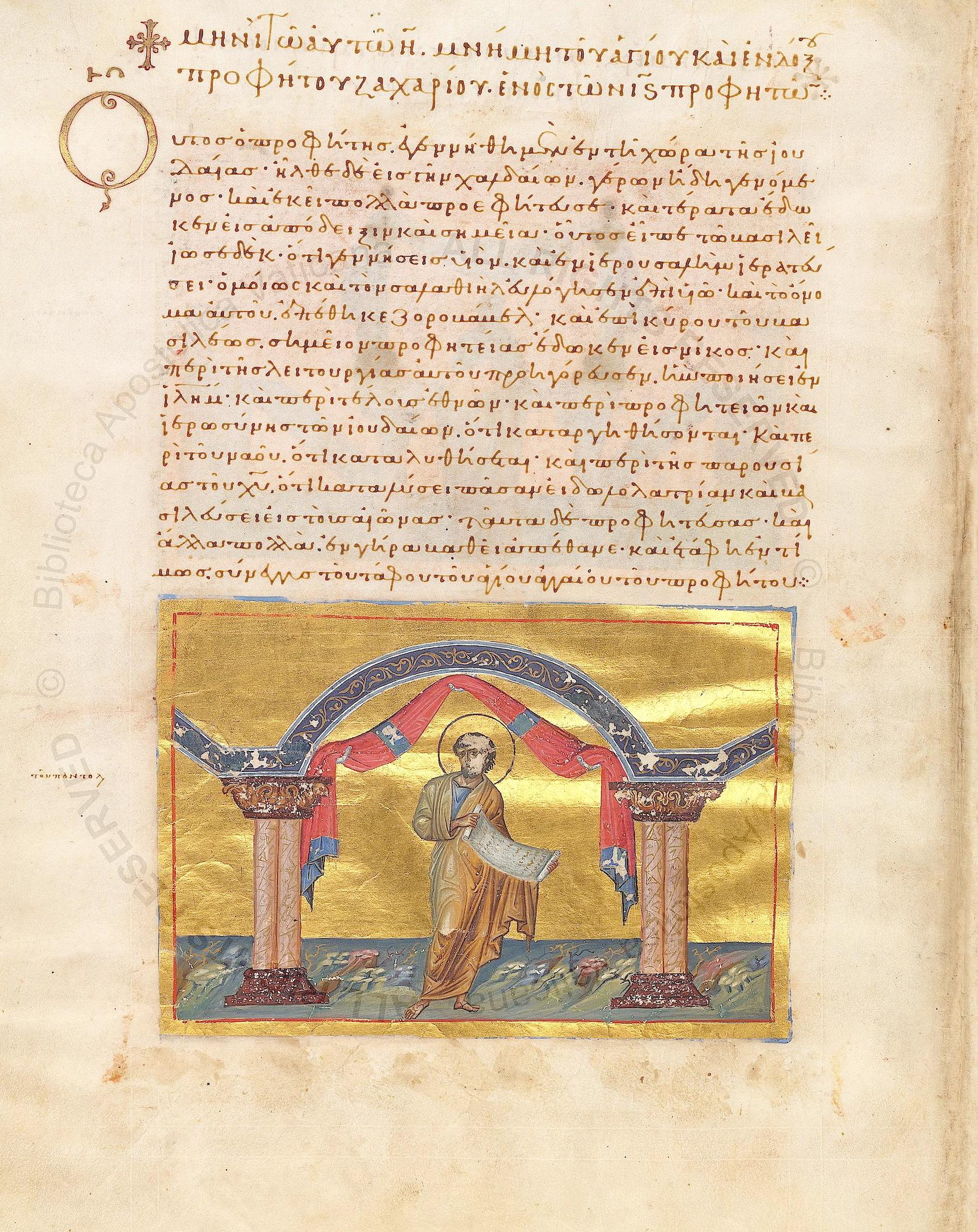

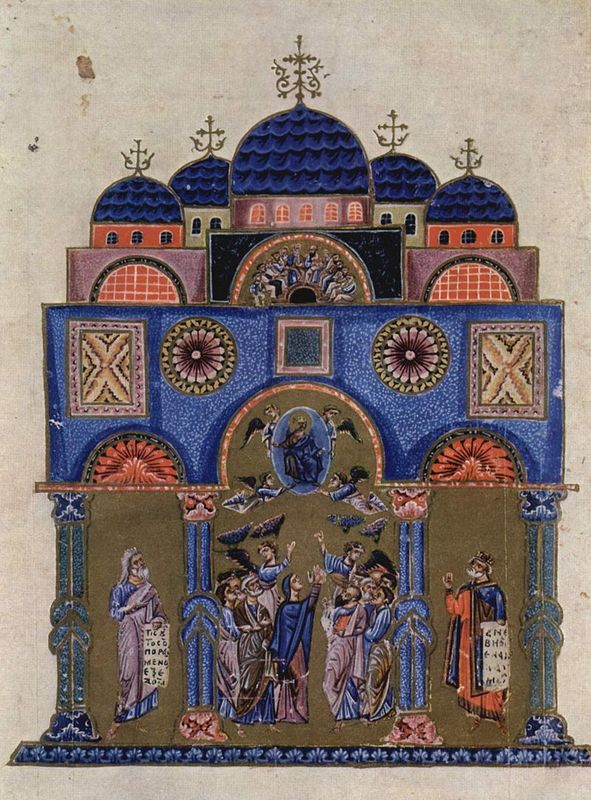

The peculiar classicism of the Constantinople school of the 10th century was also expressed in the field of book miniatures. A number of manuscripts imitating or copying old models date back to this time. Among them, handwritten books of a religious nature predominate, but there are also manuscripts of secular content, such as “Topography” by Kosma Indikoplov. The manuscript of Gregory of Nazianzus (No. 510) and especially the psalter (No. 139) from the Paris National Library are very famous. The miniatures of the Paris Psalter differ sharply from those that decorate the Khludovskaya Psalter: they are not written in the margins of the manuscript, but occupy entire pages of the codex and are enclosed in ornamental frames. Much space is given to the landscape, given in perspective, as well as the architectural background. Allegorical images are often used, personifying rivers, mountains, etc. Night, for example, is depicted as a woman with an overturned torch and a veil spread over her head, Melody sits next to King David, represented as a young shepherd playing the lyre. Monumental painting of the 11th-12th centuries.

During the 11th-12th centuries it intensifies spiritualistic character of art. The figures lose their physicality; they are placed outside the real environment, on a golden background. The architectural landscape or landscape acquires a conventional character. Elements of picturesqueness that existed previously are replaced by linear images. The coloring also becomes more conventional. Constantinople craftsmen worked not only on the territory of the capital itself. This is evidenced by the 11th century mosaics in the Church of the Assumption (now destroyed) in Nicaea and the church in Daphne (near Athens). Mosaics of the church in Daphne. In Daphne one can observe the organic unity of the structure of the building and its decorative design, which is characteristic of Byzantine art of the mature period. The mosaics are clearly visible, as they are located in the upper parts of the building; the lower part of the wall is decorated with marble slabs. Each scene is fitted with great skill into the space allocated for it. Among Daphne's mosaics, the most remarkable are the cycles of mosaics with scenes from the life of Christ and the Mother of God. The interpretation of figures, poses, gestures, and drapery of clothes indicate that the masters used ancient prototypes, but a creative use, subordinate to the content that the artists put into the scenes they depicted. The deep thoughtfulness of the entire composition, brevity in conveying the plot, restraint of gestures and care in the selection of details help to focus the viewer’s attention on the internal characteristics of the individuals involved. The restraint of interpretation does not prevent the variety of compositional solutions and characterization of characters. Refined drawing skills are combined in these mosaics with a wealth of color shades and great pictorial culture. All this gives Daphne’s mosaics a special charm and beauty characteristic of all works of true art.

Mosaics of the Daphnia Monastery

Mosaics from the Church of Luke in Phocis.

A completely different line of development of art is reflected in the mosaics of the Church of Luke in Phocis, dating back almost to the same time. They continue to a certain extent the folk tradition that marked the mosaics of the Church of St. Sofia in Thessaloniki. Rough figures of shortened proportions, graphically rendered strictly frontal faces with large, wide-open eyes, frozen poses, broken folds of clothing - all this gives a provincial look to this interesting monument.

Many individual images indicate a developed cult of saints: special veneration of local saints, as well as holy warriors, is characteristic of the ideology of feudal society.

Miniature 11-12 centuries.

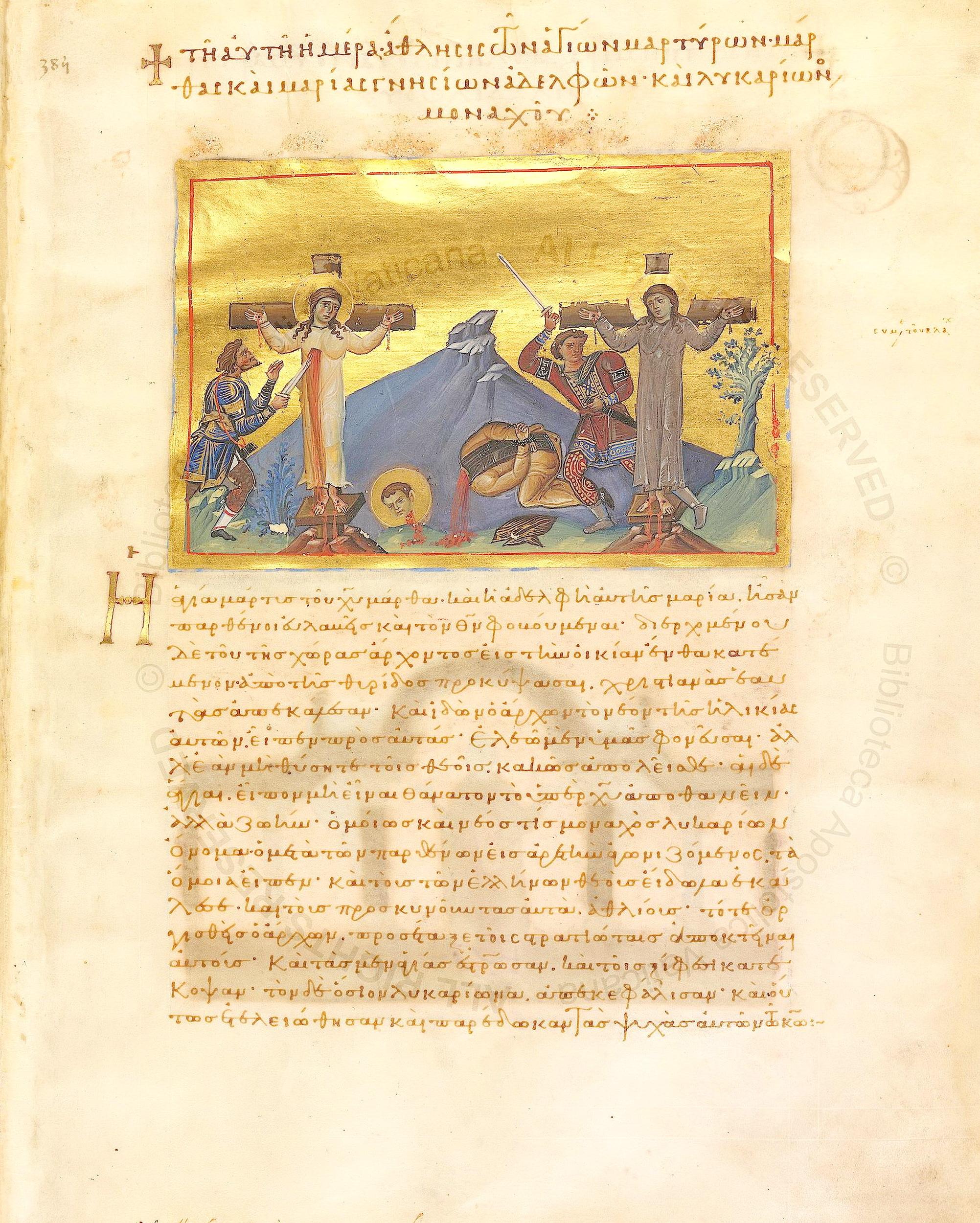

Book miniatures belonging to the same period are stylistically close to monumental paintings. The famous Menology (monthly words) of Basil II (Vatican Library), which appeared at the beginning of the 11th century, is far from classicism. The miniatures decorating it occupy part of the page and are organically connected with the beautifully written text and capital letters. Light, seemingly ethereal figures of saints stand out against a golden background. Architectural forms are generalized and given on a much smaller scale than the figures; the landscape is conventional and takes up minimal space. The miniatures shimmer with bright, pure tones - blue, red, green on a gold background.

The decoration of Byzantine books developed in this direction during the 11th - early 12th centuries: ornamental headpieces and initials, amazing in their subtlety of execution, include floral and geometric patterns, figurines of birds and animals, and sometimes people.

A particularly common type of handwritten book is the Gospel. As a rule, it begins with a picture of the evangelist; the text is often accompanied by illustrations of the main, so-called “holiday” gospel scenes. Some of the most precious codices also contain portrait images of investors or customers, most often emperors or members of their families.

Iconography 10-12 centuries.

Along with monumental, mosaic and fresco painting, a unique type of easel painting—the icon—developed in Byzantine art of the 10th-12th centuries. The role of the icon apparently increased significantly in the post-iconoclastic period (9th century). However, the number of monuments from this time that have reached us is very limited.

The technique of painting icons with wax paints, the so-called “encaustic”, gradually disappeared at this time. Egg tempera dominates. The initial contour of the image was applied to the gesso, which was then filled with the main - local tone, on top of which highlights, browning, etc. were made.

Monumental art had a significant impact on the icon. Architectural elements (arches, columns) are often found in the icon. The commonality with monumental painting can also be traced in the principles of composition. The human figure dominates the icon. The landscape and architectural background are conveyed conditionally; the number of actors is very limited. The composition is built around a figure that is central in its significance, usually distinguished by its dimensions.

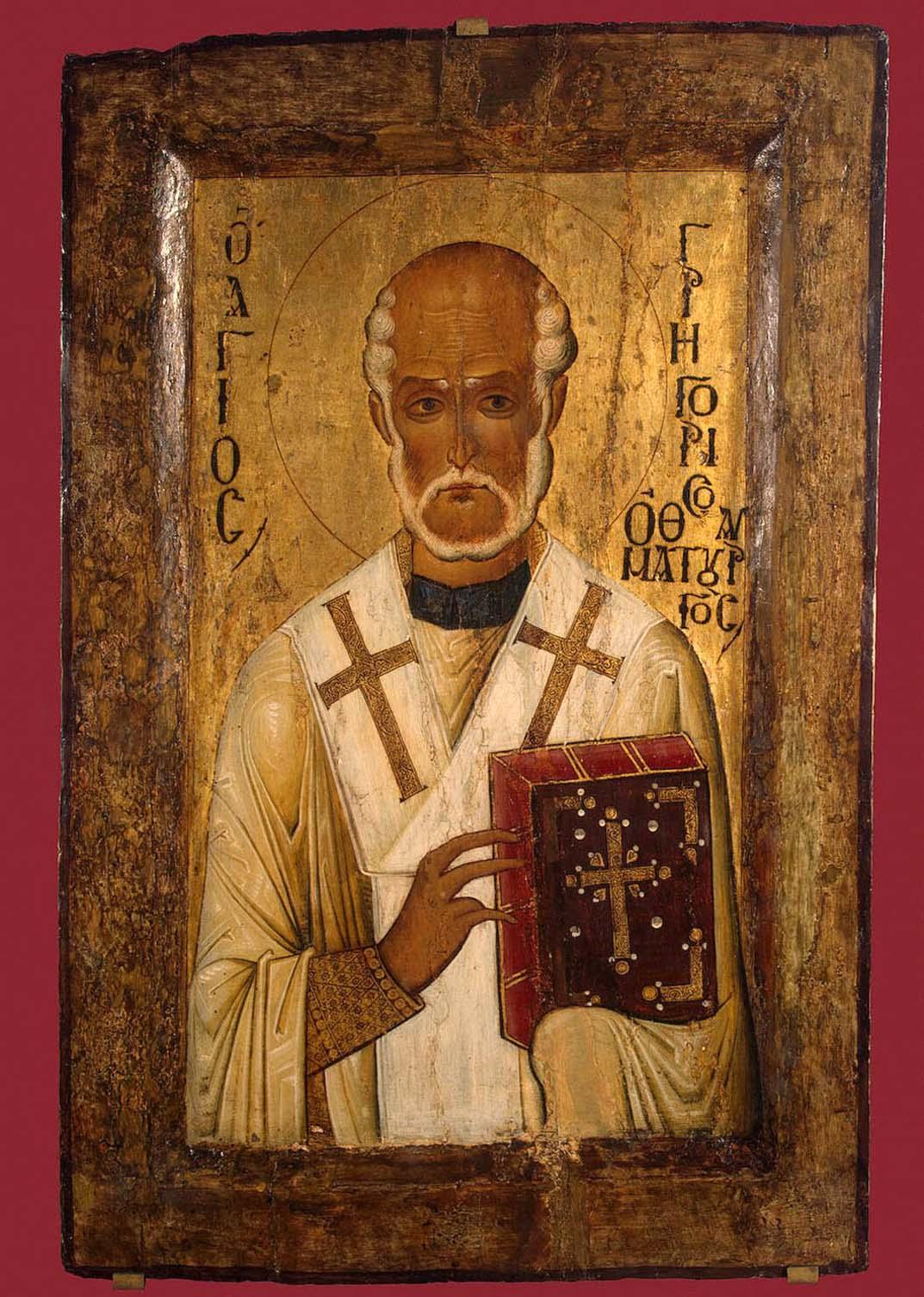

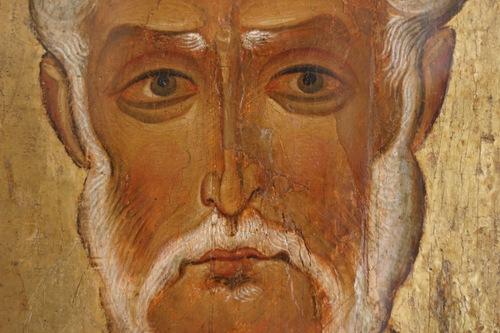

One of the most outstanding examples of icon painting is the icon of Gregory the Wonderworker from the Hermitage collection (12th century).

At first glance, it gives the impression of a monumental mosaic image, standing out against a shimmering golden background. Deep spirituality, delicate pattern of folds of clothes, restrained color scheme, general high quality of workmanship give grounds for its rapprochement with the largest work of this type of art - the icon of Our Lady of Vladimir in the Tretyakov Gallery.

This icon was cleared in 1918. Under many later layers, restorers uncovered the faces of the Mother of God and Christ, which belonged to the hand of a Byzantine master of the first half of the 12th century. The somewhat sad, deeply soulful expression on the Mother of God’s face still produces an irresistible impression. The face is given in dark olive tones, in places enlivened by pinkish-brown colors. Carmine red strokes mark the lips and corners of the eyes. The baby's serious gaze is turned to the mother; his face is painted in a lighter color scheme, contrasting next to his mother’s face. For all the spiritualistic nature of this image, the Vladimir Mother of God is deeply human and emotional. It served as a model for many later reproductions and imitations.

This icon was cleared in 1918. Under many later layers, restorers uncovered the faces of the Mother of God and Christ, which belonged to the hand of a Byzantine master of the first half of the 12th century. The somewhat sad, deeply soulful expression on the Mother of God’s face still produces an irresistible impression. The face is given in dark olive tones, in places enlivened by pinkish-brown colors. Carmine red strokes mark the lips and corners of the eyes. The baby's serious gaze is turned to the mother; his face is painted in a lighter color scheme, contrasting next to his mother’s face. For all the spiritualistic nature of this image, the Vladimir Mother of God is deeply human and emotional. It served as a model for many later reproductions and imitations.

Byzantium is a state that arose as a result of the transfer by the Roman Emperor Constantine in 330 of the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to the city of Byzantium, located on the territory of Asia Minor. Therefore, the rulers and inhabitants of Byzantium considered themselves heirs of Roman culture and called themselves Romans. Soon this city was renamed in honor of Constantine to Constantinople ( modern Istanbul- capital of Turkey). The period of development of Byzantine culture ends in the year of the fall of Byzantium under the onslaught of the Turks, in 1453. Byzantium is a huge state association, and the influence of Byzantine art is observed in ancient Rus', and in the Slavic countries of the Balkans, in the territory of the Orthodox Caucasus and Transcaucasia. In the visual arts, much was taken from the principles of antiquity, namely anthropomorphic images of God and saints. Otherwise, in terms of the interpretation of form and the nature of the lines, this art is absolutely different from ancient art. The decisive factors in the formation of trends in the artistic culture of Byzantium are religious ideas, Christian dogma, and in works of art there is not an artistic image, but a theological idea. This determines the priority of church architecture over secular architecture and the fact that even in products of decorative and applied art Christian themes prevail. . The main thing in architecture were churches, in fine arts - mosaics, frescoes, icons, book miniatures (illustrations of books such as the Bible and the Gospel). The ideologists of Byzantine Christianity believed that God and saints cannot be depicted in the way that was customary in antiquity, that is, by correctly conveying shapes and volumes. There are two reasons explaining this position: 1. Saints should not resemble pagan statues (the fight against pagan ideas). 2. Saints should not resemble people themselves, since the image of God is “incomprehensible” and “incomprehensible.” That is, the image of God is not an image of his shell, but an image of his spirit. This is precisely what explains the lack of correct proportions, volumes, and rigidity of lines. An important feature of Byzantine culture is traditionalism, the preservation of almost the same principles for more than a millennium. Periodization:

1. Early Byzantine period (4th century - ca. 730).

2. The period of iconoclasm (destruction of images and saints; 8-9 centuries).

3. Middle Byzantine period (this includes the time of the Macedonian dynasty and the Kimnin dynasty; 9th century - 1204).

4. Late Byzantine period (Palaeologian dynasty; 13-15 centuries).

In Byzantine fine art, the main ones are mosaics, frescoes and icons. It is in them that the essence of God and the saints is reflected and biblical and gospel stories are revealed through Christian subjects. Mosaics were made from smalt, frescoes were made with tempera paints on plaster, icons were made with encaustic paints (wax paints), and later with tempera paints on board. Stylistics of mosaic, fresco, relief and book images: lack of space in the visual field; flatness; conditional light-shadow modeling; rigidity of lines and design as a whole; maximum proximity of the saint’s figure to the foreground; solemnity and severity in the figurative structure; using blue and gold as the main colors as symbolic colors of Christian wisdom. The main iconographic types of images of saints: Christ the Pantocrator (“Almighty”, depicted mainly in the dome of the church); Deesis (in the center is Christ, to the right of him in a bowed position and with a prayer gesture is the Mother of God, to the left is in a bowed pose and with a prayer gesture John the Baptist (Baptist), usually in the altar part of the temple; Our Lady of Oranta (“praying”) was depicted most often in the altar apse; scenes such as Baptism, Crucifixion, Annunciation, etc.

Some examples of images from smalt mosaic: “Emperor Justinian with his retinue” and"Empress Theodora with her retinue" in the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna; "Procession of the Martyrs" from the church of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna (all examples from the 6th century); angel from the composition “Heavenly Powers” in the Church of the Assumption in Nicaea (between the 7th and 11th centuries); "The Virgin and Child" from St. Sophia in Constantinople (9th century); "Christ Pantocrator" from the monastery of Hosios Loukas in Phokis (Greece) (11th century).

Some examples of fresco images: “The Descent from the Cross” from the Church of St. Panteleimon in Nerezi (Macedonia, 12th century); an angel from the scene of “The Myrrh-Bearing Women” in the Mileshevo monastery (Serbia, 13th century);"Descent into Hell" from the Chora Monastery in Constantinople (14th century).

Some examples of icon painting: “St. Chariton and Theodosius" (encaustic, 6th century) "Deesis with saints in the fields" (tempera, 11th century); "Christ Pantocrator" (tempera, 14th century).

Some examples of book miniatures: “Our Lady” (approx. 1000 g., gold-colored miniature from the monastery of St. Catherine in Sinai); “The Nativity of Christ and the Evangelist Mark” (from the Tetraevangelium, 12th century).

There is virtually no round sculpture in Byzantine art. This is explained by the tough position of the churchmen, who considered it unacceptable to depict saints in volume (see above). There are relief compositions made of marble or more often Ivory, made in bas-relief and depicting emperors with saints or saints. Examples: diptych with scenes of circus martial arts (ivory, 5th-6th centuries, a rare example of depicting a social scene, which is not typical for later times); Our Lady Hodegetria (“guidebook”, ivory, 10th-11th centuries).

In 330, on May 11, Emperor Constantine I the Great inaugurated Constantinople, founded on the banks of the Bosphorus on the site of the former Greek colony of Vimntia. He and his followers decorated the “New Rome” with many religious and secular buildings, but in the first centuries of its existence Constantinople did not yet play a leading role in the development of Christian art. It was born and developed in Rome (until the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476) and in the large Hellenistic centers of the East - Antioch, Ephesus, Alexandria, as well as in Palestine and the Holy Places.

With the strengthening of the Eastern Roman Empire under the Justinian dynasty, and especially during the reign of Justinian himself (527-565), Constantinople became a major artistic center where the ideas and art forms of the empire and Christian iconography were developed. And although in Constantinople itself not a single example of monumental painting from this period has survived, it is quite easy to imagine the nature of this art from fragments located in other cities of the empire - Thessalonica, Mount Sinai, Ravenna, as well as from silver dishes marked with a portrait stamp Emperor.

Byzantine aesthetics

Byzantine art is known to us as religious art. The imperial palaces and houses of noble nobles were destroyed; only a few very good ideas about their decoration give general descriptions. But with the exception of purely ornamental motifs, secular art itself was influenced by religious art, which is especially noticeable in painting designed to symbolize imperial power. Fully preserving the themes. sanctified by ancient tradition, “from the end of the 6th century and especially on the eve of the iconoclastic crisis, the subordination of symbolic Christian iconography to traditional Roman models began (A. Bocharinni). In terms of form and aesthetics, this art is based on the same rules as religious art.

Some basic features of Byzantine aesthetics can be identified. One of them is the gap between image and reality. The human figure is “dematerialized”, its weight and volume seem to be muted and movement is limited. Significant and solemn characters are usually depicted from the front, their whole life concentrated in an intense gaze directed at the viewer. Everything that comes disappears; compositions are built in two dimensions that have nothing to do with the material world. Theories concerning the nature and function of the religious image, the sensory intermediary between the believer and the “supersensible,” greatly contributed to the development of this artistic language, but even ancient authors, for example, Plotinus, developed similar ideas that many things that are looked at “ spiritual eyes” can reveal the invisible.

Moreover, the tendency towards “abstraction” also appeared in the art of early antiquity, especially in the eastern provinces. In Byzantium, the heir to the Greco-Roman traditions, where the cult of antiquity always flourished, the “abstract” character never reached the level at which it existed in Eastern works. The classical canon continued to be observed. The characters, draped in antique clothes, retain, even when depicted from the front, some features of classical poses. The ancient heritage includes light and harmonious compositions, as well as the arrangement of figures along the central axis. Some themes are even inspired by ancient compositions, such as “Christ the Good Shepherd” sitting surrounded by sheep, or “David” playing the lyre and surrounded by animals - associated with the image of Orpheus bewitching the animals. This continuity with respect to the ancient tradition is another characteristic feature of Byzantine art.

Below we will see that the various Byzantine “renaissances” were distinguished by the strong influence of ancient images. However, unlike the West, Byzantium never lost ties with antiquity. The creative activity of Constantinople in its continuity was associated with constant conquests and was more or less intense depending on the different historical periods. However, art workshops have always existed, even during the iconoclastic period, when secular themes predominated. This can explain the technical superiority of the works performed by Constantinople masters. The taste for color and expensive materials is observed everywhere, whether we are talking about mosaics on a gold foil, enamel, gold and silver items, miniatures or icons also painted on a gold background.

The splendor and splendor of the churches could amaze at first glance, but this splendor was a tribute to divinity, the abode of which was to be equal, if not superior in wealth, to the palace of the emperor, vicar of Christ. Thus, Byzantine art was religious art, the formation of which was dominated by the influence of dogma and liturgy. Most of all, it is manifested in the programs of religious buildings.

Iconographic programs. IV-VIII centuries.

In a letter written around the end of the 4th century... St. Nile, in response to a request addressed to him by Eparch Olympiodor, advised the latter to depict a cross in the apse of the church he had just founded and place scenes from the Old and New Testaments on both sides of the nave, “so that illiterate people who cannot read the Holy Scriptures would recognize it with their eyes.” . This educational function of the image was also recommended by the great scholastics, who considered sight to be more important than hearing, since it allows us to better understand the meaning of the Gospel events. During the same period, another decorative system was developed. It develops in "martyriums" (buildings built on the relics of a martyr) and, especially, in monuments erected in the Holy Places of Palestine and perpetuating significant events in sacred history. The Old Testament scenes were supplemented by episodes from the life of Christ (childhood, miracles and Passion), which corresponded to various aspects of theophanic themes.

If in the West the elongated plan of the basilica predetermined the development of narrative cycles (for example, scenes from the Old Testament in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome or scenes from the New Testament in the Church of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna), then in the East, preference was given to the program arising from decoration of the martyriums, including scenes from the Old Testament and episodes from the life of Christ, considered in the aspect of theophany (however, at that time it had not yet been developed unified system). Thus, in c. in Perushnitsa (Bulgaria) biblical and gospel scenes alternated, and in the Basilica of St. Dmitry in Thessaloniki, the idea of piety was expressed in a mosaic in the form of ex-voto. IX-XI centuries Square in plan and topped with a dome, the church was likened to a microcosm; its structure resembled the structure of the Universe. The type of decoration, known to us mainly from descriptions of the 9th-10th centuries, focused attention on this symbolism of the Christian world, according to which the church is the earthly heaven where the Heavenly Father dwells. From the dome, that is, from heaven, Christ, as it were, “observes the Earth and reflects on its structure and governance.” On this Earth, the prophets, apostles, martyrs and church fathers depicted under the dome symbolize the church “anticipated by the patriarchs, announced by the prophets, founded by the apostles, perfected by the martyrs and adorned by the fathers of the church.”

But christian world, predicted by the prophets, can only be established on the basis of the Incarnation, the instrument of which is the Mother of God depicted in the apse. This type of decor, which is rather abstract in nature, is gradually giving way to another, which has become widespread. The images of Christ Pantocrator and the Mother of God are still depicted in the dome and apse, and various categories of sacred characters are preserved, but the idea of salvation is now expressed in gospel scenes associated with the Incarnation, Passion and Resurrection of Christ. In liturgical documents there are lists of the “Great Feasts” of the Savior and the Mother of God, which vary in different lists; these differences are especially sensitive in monumental art, since the number of images in the church depended on the space available in it. From the 11th century the minimal program included the main events from the life of Christ and the Dormition of the Mother of God. The Communion of the Apostles was preferred to the Last Supper.

Behind the altar, where the priest prepared the Eucharistic sacrifice, Christ was depicted giving bread and wine to the apostles. In basilica churches, especially in Cappadocia, for a long time they adhered to ancient techniques: the theophany was depicted in the apse, and on the walls a narrative cycle unfolded in which scenes. corresponding to church holidays were not highlighted. XII-XV centuries Mosaics were preserved in the upper parts of the temples, but from the 12th century. it increasingly gives way to fresco, which begins to occupy the entire surface of the walls and vaults. This led to the development of iconographic programs. So. author of the late 11th century. wrote: “Those who bear the title of priest know and recognize what happens in the liturgy - the depiction of the passion, burial and resurrection of Christ. But they forget that the liturgy also recalls minor episodes of the appearance of Christ, salvation, the virgin birth, baptism, the calling of the apostles...”

For other ecclesiasts, the liturgy is also connected with all episodes of the Gospel story. The same ideas inspire artists who develop iconographic cycles. In addition to the main event, secondary episodes are depicted, supplementing them with miracles and parables and giving an important place to the apocryphal life of the Mother of God. In addition, scenes from the life of the church's patron saint and other saints are presented, as well as a liturgical calendar and menologies. depicted on the walls of the narthex along with special images for each day of the year. The influence of the liturgy affects other innovations as well. If earlier the holy bishops were depicted from the front and in full growth inside the semicircle of the apse, now they perform sacred acts, turning to the altar on which the Child Christ is presented. The communion of the apostles is complemented by a solemn procession, during which gifts are presented to the altar; this image is conceived under the sign of the Eternity of the Divine Liturgy, which is served by Christ with the angels.

The influence of the liturgy, as well as the increasingly flourishing cult of Our Lady, encourages artists to illustrate hymns dedicated to her. Each of the 24 stanzas of the “Akathist” glorifying Mary is illustrated. The compositions, inspired by the Christmas surplices, depict the whole world bringing its gifts to the Mother of God and the Child. Believers are also depicted around the icon of the Mother of God, singing hymns in her honor. The biblical scenes introduced into the composition are also associated with the image of the Mother of God, since the episodes with Jacob's ladder, Moses and the Burning Bush and others are considered as images or prototypes of Mary and the Incarnation. The connection between the decoration of the church and the history of the Church was expressed by the depiction of the Ecumenical Councils. An image of the Last Judgment was often placed on the walls of the narthex. The entire encyclopedic program developed in this way throughout the 13th-14th centuries. and was closely connected with church dogma and liturgy. Stylistic development. Early period (IV-VIII centuries): wall painting and mosaics. In general, the early period of development of Byzantine painting was a transitional period - from the art of late antiquity to Byzantine art. In c. St. George in Thessaloniki, the portraits of martyrs still obey the classical ideal of beauty, and the architectural backgrounds are based on ancient images of ancient theaters. In the Basilica of St. Dmitry in Thessaloniki, figures presented in two dimensions, in motionless poses, with schematic folds of clothing indicate a style increasingly moving away from the artistic language of antiquity. However, these gradual transformations are not the general rule. Other works are characterized by hesitation, backtracking, or both.

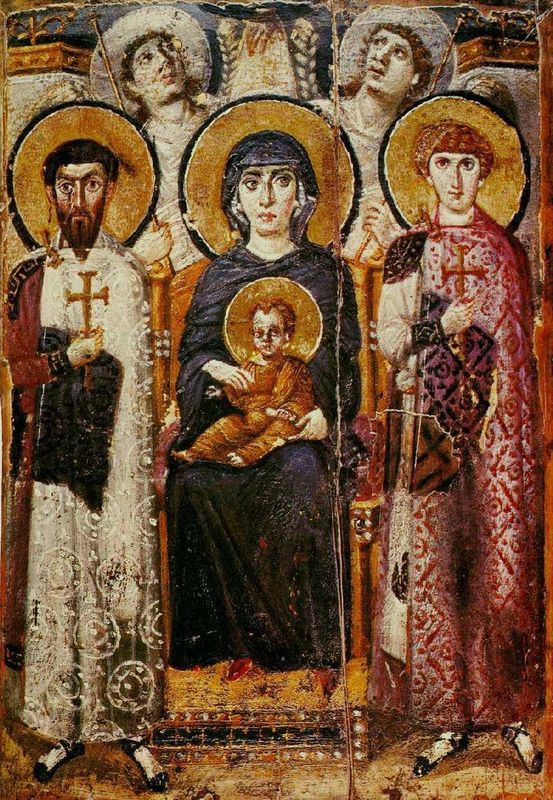

Many silver dishes with chased images are marked with hallmarks from the reign of Emperor Heraclius I (610-641). Some are decorated with mythological subjects, others with scenes from the life of David, but all of them bear the stamp of the ancient style in the interpretation of volumes and in the poses of the characters. On the contrary, on a silver paten dating from the reign of Justin II (565-578, Constantinople, museum), the “Communion of the Apostles” is performed in a linear style without any trace of ancient tradition. However, the stylistic differences are not related to the depicted plot, since on another paten (Washington, Dombarton Oak Museum), also created during the reign of Justin II, the “Communion of the Apostles” is interpreted in plastic, close to anti-inflammatory dishes depicting mythological and biblical subjects. Other works, such as large icons of “St. Peter". “The Virgin and Child Enthroned Surrounded by Angels and Two Saints” testify to the coexistence of two trends in the Constantinople workshops: on the one hand, the use of artistic techniques of the Greco-Roman era and attention to the plasticity of the human figure, and on the other hand, linear style and search "spirituality".

Iconoclastic period (726-843)

The flourishing of religious art was interrupted for a century by a crisis that shook the entire empire. Religious and, partly. For political reasons, the Byzantine emperors tried to put an end to the ever-increasing cult of pictorial images of saints. In 726, Emperor Leo III ordered the removal of the illustrious face of Christ from the Bronze Gate of Constantinople, and in 730 he also issued a decree prohibiting the depiction of saints, scenes from the life of Christ, the Mother of God and saints, and in addition, authorized the destruction of existing images. Mosaics and frescoes were destroyed or covered with lime, icons were broken, and miniatures were torn out of manuscripts.

With a short break (787-815), the iconoclastic period continued until 843, when the decision taken at the Ecumenical Council to restore the images was announced at a solemn ceremony and presented as a triumph of icon veneration. This event is still honored by the Greek Church today. The iconoclast emperors were not at all opponents of art; secular subjects were not cursed during their reign. According to historians, religious scenes in churches were replaced by “trees, various birds and animals, in an ivy pattern, where cranes, crows and peacocks were intertwined.” Constantine V (741-775) replaced the images of the six ecumenical councils with the image of his beloved charioteer. Rivaling the splendor of the residences of the Baghdad caliphs, Theophilus (829-842) decorated the walls of the pavilions built around his palace with various ornaments consisting of animals and birds, trophies and shields, as well as images of statues. Portraits of emperors and members of their families also continued to exist.

Macedonian Renaissance (IX-XI centuries)

The Byzantine Empire reached its greatest prosperity during the period from the accession of Basil I (867) to the death of Basil II (1025). The imperial armies pushed the Arabs back into Asia Minor and conquered Sicily, Syria and Palestine. In Europe they put an end to the power of the Bulgarian kings and occupied Macedonia and Southern Italy. The baptism of the Slavic population of the Balkans through the mediation of Byzantine missionaries and the baptism of Rus' expand the geography of influence of Byzantine culture. The university is being restored in Constantinople, the communication of people brought up on the works of Greek antiquity gives rise to what contemporaries will call the second Hellenism. Parallel to this intellectual revival was an artistic revival. This concept should mean a powerful rise in artistic activity simultaneously with the renewal of the ancient tradition. The first works created in Constantinople after the triumph of icon veneration are known only from descriptions (the face of Christ restored on the Bronze Gate, before 847, the decoration of one of the churches in the palace, c. 864, the decoration of the palace state hall, Chrysotriclinion. 856-866).

But since 867, the date of the discovery of the majestic image of the Mother of God in the apse of Sophia of Constantinople, numerous mosaics and paintings appear in Constantinople and Thessaloniki. Nikeya, Ohrid, Daphne. Besides. Many of the rock churches of Cappadocia are remarkable examples of provincial art and the penetration of metropolitan influence into it. The taste and meaning of color is revealed in all its splendor in sparkling mosaics that seem to radiate light. Byzantine artists do not strive to reproduce the exact shades of objects or elements of the landscape; they care more about color harmony and skillfully combine compositions and individual figures with the architecture of the church itself: standing figures are located in the drum of the dome and arches, half-figures in lunettes, busts fit into medallions on the formworks of the vaults and at the top of the arches. Behind the apparent simplicity of the compositions lies the exact science of the arrangement of figures, the balancing of masses, the relationship between filled and empty spaces. A sense of classical beauty reigns in the works. directly associated with Constantinople, but the search for ideal beauty goes hand in hand with the spiritualization of expression. A deep sense of restraint gives all images great dignity, emotions are expressed by a slight movement of the eyebrows or a barely indicated gesture. Random details are completely excluded. Placed in a surreal world, against a golden background, the figures are depicted in calm poses, harmonious compositions seem to be outside of time and space, like those clear truths of which they are a visible image.

Age of Komnenos (1081-1204)

After the political decline of the heirs of Basil II and the loss of Asia Minor, conquered by the Seljuk Turks, the feudal family of Comneni comes to power, which restores the former power of the empire. These emperors patronized scientists, scholars and artists; during their reign, Constantinople again experienced the flourishing of culture. Writers close to the imperial court were in love with classical culture, but in religious works mysticism began to come to the fore. It was said above that this influence is most manifest in iconographic programs. Hymns of Simeon the New Theologian, the great mystic of the late 10th and early 11th centuries. full of tenderness for the Savior and emphasize the humility of the suffering Christ. These works help to understand the image of the compassionate Christ, which replaced the stern figure of Pantocrator and the tender and mournful expression of the Mother of God (for example, in the icon “Our Lady of Vladimir”, which came from Byzantium to Ancient Rus') and, especially, acute emotions in the scenes of the Passion.

There is a huge difference between the strict and restrained classical style of monuments of the 10th-11th centuries. and frescoes in the c. St. Panteleimon in Nerezi (1164), which mark important stage in the development of Byzantine painting. Art trends of the 12th century. manifest themselves in a more pronounced desire for reality, in the desire to individualize traditional types, in the interpretation of episodes where feelings of grief and tenderness are expressed with great force. The figures become more ascetic and lose their monumentality, the restless folds of clothing convey movement, and the graphic depiction enhances the expressiveness of the faces. By the end of the 12th century. these tendencies lead to a kind of mannerism, exaggerated dynamism, which often has no direct connection with the depicted episode.

Palaiologan era (1261-1453)

After the return of independence to Constantinople, occupied by the Crusaders in 1204-1261, the Byzantine Empire decreased territorially. She was threatened from all sides, and from within she was torn apart by civil strife. However, she experienced her final heyday. The study of classical antiquity, scientific and philosophical writings, in particular, the works of philologists foreshadowed and prepared the humanism of the Italian Renaissance, were again honored. Luxurious churches were erected and decorated everywhere. The mosaic, which had disappeared, regained popularity and was widely used in the church. Kakhriye Jami in Constantinople. Artists of this period abandoned the mannerism of the late 12th century: they replaced the linear style with relief images, which, using patches of color, show shapes and often appeal to earlier works of Byzantine painting. performed in the ancient tradition.

Imitation of antiquity, majestic characters, siennas, deployed in a natural frame and enlivened by a lyrical impulse, were most brilliantly reflected in the 13th century. in painting c. St. Trinity in Sopochany, and in the 14th century. (with fairly obvious stylistic differences) - in mosaics and frescoes c. Kakhrie jami. Artists of the Palaiologan era adopted and developed trends that appeared in the 12th century. The compositions are enriched, the number of minor characters and accessories increases. A dynamic crowd is positioned in the center of a landscape or architecture depicted in such a way as to convey some impression of space. Picturesque details, sometimes borrowed from Everyday life, enliven religious scenes, at the same time the episodes of the Passion are given a pathetic character. Art of the 14th century more often seeks to touch the viewer with an expression of tenderness than to excite him with the depiction of suffering. The powerful art of the 13th century, which expressed an interest in reality and imitation of nature, suggested further evolution in this direction, but gradually it gave way to art, still marked by deep spirituality, but in which the search for elegance and decorativeism was already dominant. It can be assumed that this retreat was caused by the victory of the mystical sect of hesychasts over the rationalists, among whom was the monk Varlaam (c. 1290-1348).

For hesychasts, faith is a vision of the heart that exceeds the capabilities of the mind; with the help of contemplation, a person can comprehend the invisible. This concept of the irrational reality of divine things alienated artists from the search for material reality and delayed the innovative movement of the 13th century.

Post-Byzantine period

The capture of Constantinople by the Turks in 1453 put an end to artistic experiments in the capital and others major cities. Creative activity was now concentrated in monasteries on Mount Athos, in Meteora (Thessaly), on the island of Crete, which escaped Turkish rule, as well as in some cities, for example, in Kastoria. The art of this period relied to some extent on the conquests of previous eras and sought to preserve the resulting heritage. Contact with the West sometimes introduced new themes to this art, but had no significant influence on either its style or spirit.

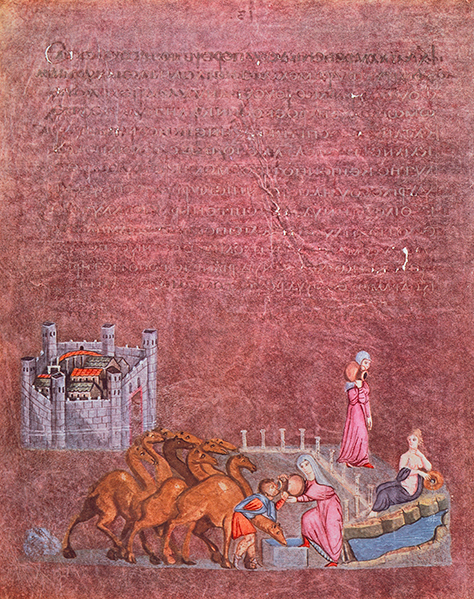

Miniature. Miniature painting was an important part of Byzantine art. In a certain sense, the miniaporists were more faithful to ancient models than the frescoists and mosaicists. Just as scribes meticulously copied the text, artists reproduced the illustrations just as accurately. The miniaturist nevertheless enjoyed greater freedom, since he was less subject to the dictates of dogma and liturgy. Thus, in the art of miniatures we see, on the one hand, works closer to the ancient tradition than in monumental painting; on the other hand, miniatures cannot be found in analogues in the decoration of churches. The many surviving illuminated manuscripts provide insight into the various stages of the development of Byzantine painting. Miniatures of the 6th century. In the VI century. Three magnificent manuscripts were created, partially preserved, written on purple parchment in gold and silver letters: the book of Genesis (Vienna Genesis, Vienna, National Library, cod. theol. gr. 31) and two Gospels (Rossano. Italy, cathedral, and Paris. National Library).

In the book of Genesis, illustrations are contained on 24 sheets, they were executed by different artists: genre scenes written in the Hellenistic manner complement the text, providing it with pictorial details, landscapes and allegorical figures, miniatures are located at the bottom of the page, most often without a frame. The pictorial style of the two “Gospels” is completely different: here all minor details are expelled from strict compositions, reduced to the figures of the main characters necessary for reading the plot. The majestic nature of the image, the solemn characters are in full agreement with the deep meaning of religious scenes. in many of which open expression prevails (for example, “Prayer of the Cup”), in other scenes the artist was inspired by images of imperial art.

Miniatures of the 9th-11th centuries. Numerous psalters of this time with illustrations in the margins represent the most original section of Byzantine art. The vignettes, executed in a lively, realistic style, form a kind of visual commentary on episodes from the life of the people of Israel; they are related to the psalms and gospel scenes which they anticipate. This group of miniatures is adjacent to others, testifying, referring to historical events era - to the polemics of the times of iconoclasm (thus, the iconoclast emperors depicted here are compared with the executioners of Christ). Other psalters were decorated in the 10th century. large full-page compositions, real paintings written in the ancient manner: the most famous of them is the “Parisian Psalter” (“Greek Psalter”. Paris, National Library, gr. 139). Sometimes it was considered a work of the 7th century. due to the archaic nature of full-page miniatures. In fact, it is one of the main monuments of the Macedonian Renaissance of the 10th century.

The miniatures of the “Paris Psalter” are unequal. but many of them (for example, “David Playing the Lyre,” inspired by the allegory of Melody, or “The Prayer of Isaiah,” surrounded by allegorical figures of Night and Morning) testify to the highest skill of the miniaturists of that era. In the David and Goliath miniature, the figure of David is supported by the figure of a winged girl, symbolizing power, while behind the figure of Goliath we see the distraught and fleeing figure of Boast. In terms of the nature of the compositions, the depiction of landscapes, the relief of draperies, the majestic posture of the characters, the ideal beauty of the faces - these miniatures are much closer to ancient examples than monumental painting. On a parchment scroll from the Vatican Library ("Joshua Scroll"), scenes from the life of Joshua follow each other in the form of a long frieze; the drawing of these miniatures, animated by allegories, is another remarkable example of antique art. Connections with ancient images become more obvious when we talk about the works of ancient authors or images of evangelists and prophets.

Byzantine miniaturists made excellent use of the aesthetics and techniques of ancient painting, but the quality of the miniatures is very uneven; They also differ in style. Thus, in the miniatures of the manuscript “The Words of Gregory of Nazianzus” (Paris, National Library, gr. 510), created around 880-883 for Basil I and Empress Eudoxia, some leaves are executed in the best ancient traditions (“Vision of Ezekiel” - the beautiful face of the prophet . Mshishnyury XI-XII centuries. At the end of the X - beginning of the XI century. The miniaturists instilled in Byzantine aesthetics the antique manner in which they worked. Excellent examples of these changes are the Menology and the Psalter, performed for Basil II (976-1025). Eight artists worked on the “Menologies” (Vatican Library. gr. 613), each of whom signed his name. The buildings and landscape here resemble a backdrop and do not create a sense of real space; forms are refined, dynamism is softened. Differences from artists of the 10th century. especially noticeable when comparing scenes from the life of Davila from the “Psalter of Basil II” (Venice, Marciana Library, gr. 17) with the miniatures of the “Parisian Psalter”. Allegories disappear, and characters located on the same plane lose their majesty. But these the miniatures, like other imperial orders, were executed with very great skill.The collection “The Words of John Chrysostom” (Paris, National Library, Coislin 79), created by order of Emperor Nikephoros III Botaniates (1078-1081), is decorated with many portraits of emperors and empresses In the miniature depicting the emperor standing between John Chrysostom and the Archangel Gabriel, the expression of the ascetic ideal on the face of the saint contrasts with the firmness of the classical canon of the figure of the archangel.

Another miniature of the same manuscript shows the emperor surrounded by senior courtiers and standing in a motionless pose, presiding over the ceremonial. Here preference is given to decorative effect and luxurious clothing, but the half-figures of angels behind the throne still retain some softness of poses and volume, despite the tendency towards linearity. Linearity and abstraction are more characteristic of other works of the 11th century. In the “Psalter”, written in the Studite monastery in Constantinople in 1066 (London, British Museum, 19.352), and in the “Gospel”, probably executed in the same workshop (Paris, National Library, gr. 74), fragile figures have no more weight or volume, but their silhouettes remain elegant and drawn with a confident line. Only the faces are depicted in relief.

The network of fine gold lines covering the clothing imitates the art of enamel and emphasizes the iridescence of color. The Gospel story is illustrated down to the smallest detail. The same features of the narrative composition are characteristic of the “Gospel” of the early 12th century. (Florence, Laurentian Library, Plut. VI-23). But here there is a completely different iconography of the scenes, but also a different style: the characters seem more stable, the draperies are more prominent, the poses are more varied. IN general outline, the miniature of the Komnenos era is marked by a return to classical models, but does not imitate them, as in the 10th century. Ornament also begins to occupy a significant place, adding a unique charm to these works. One of the best examples of this group is the "Gospel" from the Palatine Library in Parma (Palat. 5). The main part of the manuscripts known to us dates back to the 11th-12th centuries. The Octateca (the first eight books of the Old Testament) have narrative illustrations as detailed as the Gospel miniatures from Paris and Florence (in the latter manuscript the miniatures are arranged as ribbons in the text). The “Psalters” are illustrated with miniatures in the margins or on a whole page. Among the works of the church fathers, preference is given to the “Words” of Gregory Nazianzus. Miniatures were also created for the “Christian Topography” by Cosmas Indicoplov, an author of the 6th century, and the mystical work “The Holy Ladder” by John Klimak, another author of the 6th century. During the Komnenos era, a series of miniatures for the “Oath of Our Lady” was created, attributed to the monk Jacob from the monastery of Kakkinobaplos, depicting episodes from the life of Mary. The crisis of miniature art (XIV-XV centuries). The art of miniatures no longer seems to play the same role as in previous centuries. The interest of humanists in ancient authors is manifested in the manuscripts of the medical works of Hippocrates, the Idylls and the short poems of Theocritus and Dosiades, the miniatures for which are inspired by ancient examples. From this era also came the “Gospel” in Greek and Latin, illustrated with many miniatures (Paris, National Library, gr. 54). Expansion of Byzantine art.

Throughout the thousand-year existence of the Byzantine Empire, its art shone in the countries it conquered or adjacent to it and extended far beyond its borders. His influence was especially strong in Northern Italy (Ravenna, Castelseprio), Rome, and later in Southern Italy and Sicily. Masters. those who came from Constantinople introduced their iconographic repertoire and their techniques into these regions, they trained local artists who continued to work in the same tradition, sometimes interpreting it depending on their talent and taste. From the beginning of the Palaiologan era and, especially, in the works of the 13th century. began to better understand the "Greek manner" and the role of this art at the beginning of the Italian Renaissance. Byzantine objects were distinguished by their extraordinary sophistication, thanks to which Byzantine influence spread throughout Western Europe. To decorate his church, Didier, the abbot of the Monte Casseno monastery not only invited Constantinople mosaicists, but also in 1066 ordered a bronze gate decorated with gold, silver and blackened figures. The wealthy Amalfi merchant did the same before him: this gate served as a model for Italian sculptors. In the Latin principalities of the Levant. founded by the Crusaders, Byzantine influence manifested itself in manuscripts illustrated in Jerusalem or in Saint-Jand'Acre. In the East, Christianity became the main vehicle of the artistic influence of Byzantium. The Slavs - Bulgarians, Serbs, Yugoslavs and Russians belonged to the Byzantine school, and their art flowed directly from art of Byzantium. The same thing happened in Orthodox Georgia, and to a lesser extent, in Armenia. After the 14th century, Byzantine influence penetrated into Romania. Byzantine painting itself often turned to other forms of art. In decorative art, motifs created by by the Sassanid Persians and perpetuated by the Muslims; after the 12th century, closer ties were established with the Latins, especially in sculpture. On the whole, however, Byzantium was a great initiator, it gave more than it received.

The history of Byzantine painting can hardly be written at this time. Our ideas about this art and its thousand-year life are naturally based on the information we have about it. But this information is very incomplete and completely random. They are so incomplete and so random that we do not even know to what extent they are incomplete and to what extent they are random. The only reliable evidence of art is provided by its monuments. The monuments of Byzantine painting known to us so far, neither in the sense of their distribution by era, nor in the sense of their territorial grouping, nor, finally, in the sense of the hierarchy of their artistic qualities, do not correspond to any order. All these are the remnants of the destroyed thousand-year-old world, its scattered traces, spared by time and historical fate with all the whimsical selection and juxtaposition with which they mark their path destructive forces time and

life.

It is not surprising that the history of Byzantine painting has until now always been rather a theory of Byzantine painting, changing depending on the conclusions for which the presence of its famous monuments gave rise. This presence itself changed depending on new discoveries that followed the spread of historians’ attention to new territories in science, to new provinces of Byzantine art. Over the past thirty years, the extent of such territories has increased many times and the number of known monuments has increased many times. In direct connection with this, the theory of Byzantine art entered a period of very lively and generally fruitful discussions. It has become a testing ground for many very brilliant, if sometimes ephemeral, constructions. And there is no reason to say that this period is over. The availability of monuments of Byzantine art increases every year, our knowledge expands and deepens every year. As long as this is so, the theory of Byzantine art will remain alive and will retain that somewhat violent desire for truth, which has made it so attractive to researchers for thirty years now.

How different the position of the modern historian of Byzantine painting is from the historian of bygone times can be seen from the fact that N.P. Kondakov in the 70s of the last century undertook his wonderful work “The History of Byzantine Art from Miniatures of Manuscripts.” Now this kind of research would be understandable as auxiliary work, only indirectly useful for illuminating well-known monuments of monumental and easel painting. During the time of N.P. Kondakov, the number of monuments of this kind available to his attention was so limited that he, of necessity, had to guess the thousand-year life of Byzantine painting only by its reflection in another art, which lived, perhaps sometimes in parallel, but still its own life - in the art of miniatures . Follow N.P. In this regard, it would now be almost as strange for Kondakov as studying the history of Italian Trecento and Quattrocento painting solely according to the data of Italian miniatures of this era.

A very noticeable step in terms of broadening the horizons of researchers of Byzantine art was made at the turn of two centuries, thanks to a new formulation of the question of its origin. Labor D.V. Ainalova about the Hellenistic foundations of Byzantine art and Strzygowski’s book “Orient oder Rom”, which was sensational in its time, opened up broad perspectives for the Byzantine question, outside of which, of course, its correct consideration could not be undertaken. One after another, many areas came under observation where Eastern Christianity directly replaced the Hellenistic East - North Africa, Palestine, Syria, Asia Minor, Mesopotamia and Armenia. Strzygowski, who made a number of scientific expeditions, especially showed a rare entrepreneurial spirit in the sense of discovering and developing more and more new “fields” of historical and artistic research.

On the other hand, in the first quarter of this century, a lot was done to clarify the final era of Byzantine art, which remained completely unknown to the Byzantinists of the time when N.P. Kondakov undertook the experiment of his “History”. This era is marked in the history of Byzantium by its cultural mission among the Slavic and other neighboring peoples, which it introduced to Eastern Christianity. It is not surprising that numerous and very important monuments of the Byzantium of the Komnenov and the Byzantium of the Palaiologos were discovered in Macedonia, Bulgaria, Serbia, Russia and Georgia. If we add here the significantly in-depth and expanded study of medieval Italy over the past twenty-five years, invariably associated with Byzantium, as well as an assessment of the diverse and multi-temporal influences of Byzantium on Western art in general, then the abundance of new historical and artistic material that has accumulated will become clear to us. The presence of currently known monuments of Byzantine art, in particular Byzantine painting, is so significant that this circumstance for the first time ensured the appearance of such works summing up all previous private works, such as the books of Diehl, Millet, Dalton and Wuiff.

And yet, as mentioned above, the history of Byzantine art, and especially the history of Byzantine painting, is not written in the monuments that have reached us. The most calm and cautious researcher cannot limit himself here to just a simple commentary on the irrefutable logic of the historical evidence itself. This logic does not exist, and he must create it himself so that random, scattered and sometimes contradictory materials can become the basis of his synthetic judgment. In an effort to remain as close to the truth as possible, he builds a historical system covering all currently known monuments. But he must always be prepared for the fact that new discoveries will not fit into the constructed system. He must always be ready to reconstruct the historical order created by his conclusions on the basis of the monuments known to him. These changes are taking place and will continue to take place before our eyes. In such conditions, the history of Byzantine painting is hardly achievable for us, and each new work in this area does not yet go further than a new theory...

With all our significantly expanded and deepened knowledge over the last quarter of a century in the field of expansion of Byzantine art in the West and East, North and South, we still know only a completely insignificant portion of the arts that once adorned the very capital of Byzantium, the main focus of all its amazing centuries-old culture - Constantinople, so expressively called Constantinople by the ancient Slavs. This is particularly applicable to the art of painting. As B. Bernson very correctly noted in one of his articles, our judgments about Byzantine painting are similar to those judgments that could be made about European painting of the 19th century by a person who had never seen Paris and did not know Delacroix, Courbet, Manet, or impressionists, nor Cezanne, being forced to form an idea about them only on the basis of their German, Italian or Russian followers, imitators and simply contemporaries. Without knowing the painting of Constantinople from the 6th to the 13th centuries, we should not hope to completely replace this knowledge with acquaintance with the works of Byzantine masters in Italy or Russia.

Meanwhile, we know, and even then only in a far from complete form, a list of those lost to us pictorial or mosaic cycles of Constantinople, which undoubtedly had a decisive significance for the entire history of Byzantine art. For now, we can only point out some of the most important gaps in our knowledge, starting with the fact that even the mosaics of the walls of Hagia Sophia are inaccessible to us, which we must judge from sketches and descriptions made almost a hundred years ago by random people in the event of repair work on a site that had been torn away from Christianity. Great Temple. Hesenberg's descriptive work will not replace, of course, what acquaintance with the original mosaics of the 6th century in another famous Constantinople church - the Holy Apostles - would give us. And all our judgments about the brilliant "flourishing" of the arts under the emperors of the Macedonian dynasty remain largely only literary speculation, since we do not know the great temple of Nea, built by Basil 1 (881) and which was the central monument of the various arts of this period. "L"or, l"argent, les mosaiques, les marbres admirables, emplissaient les voutes et les parois de la nef... Le sol de l"eglise etait pave des magnifiques mosaiques de marbre, representant des animaux etranges, des plantes, mille sujets divers, a l"imitation des plus beaux tapis orientaux. Cinq coupoles profondes, etincelant des feux des mosaiques a fond d"or, dominaient cet ensemble d"une richesse incroyable..." (G. Schlumberger. Nicephore Phocas). But what can we say about the favorite church of Roman III (1028-1034), Peribleptos, the decoration of which became the main task of his reign, about the temple of Michael IV (1034-1042), the Holy Unmercenaries, where Psellos saw how “the whole building sparkled with golden mosaics and this holy place was decorated with the art of painters who depicted, wherever possible, images , seemed alive,” what can we say about the temple-tomb of Komnenov Pantocrator, about dozens, about hundreds of other Constantinople churches, monasteries, destroyed, wiped off the face of the earth or inaccessible to us, hiding, perhaps even now from the indifference of the world, the traces of the great past under the pitiful plaster of a Turkish mosque. The fate of these remnants of one of the most durable, immobile, traditional and conservative cultures of humanity, which is still in captivity of a people to whom all its immovable values are absolutely alien - even the very idea of \u200b\u200bconnection with our past, the idea of our continuity is alien. .

What the monuments of the churches of Constantinople could be for us if they were known to us at least in a hundredth part of their former completeness is evidenced by the enormous importance that they acquire every time in the history of Byzantium new find, bringing us closer to understanding the metropolitan level of Byzantine arts. Mosaic fragments of Thessaloniki churches amaze researchers with a mastery of execution unknown in other examples; The mosaics of the provincial, ultimately, monastery of Daphne in Attica, close to Constantinople, are brought to the very forefront of Byzantine monuments due to their relative proximity to the capital, although this may not have been their previous place in the hierarchy of metropolitan Constantinople art of the 11th-12th centuries. The mosaics that somehow miraculously survived in one of the Constantinople churches of Noga (Kahrie-Jami) barely become accessible to researchers when they instantly overturn all previous ideas about Byzantine painting of the last period.

And that's not all. The churches of Macedonia, Italy, and Russia can give us some idea of the churches of Constantinople. But there is nothing that could guide us in assessing those countless works of art that decorated the palaces of the Byzantine emperors and Byzantine nobles. Let us imagine our knowledge of Italian art of the 14th and 15th centuries to be limited only to what is found in churches. Let us assume that nothing of the paintings on the walls of the palazzo and castelle, nothing of what these walls contained, has reached us. The ratio of “secular” and “ecclesiastical” painting was, of course, somewhat different in Byzantium: in the East, perhaps, “ecclesiastical” art absorbed a relatively large share of artistic energy. And, however, “secular” Byzantine painting existed - brief instructions from historians testify to its numerous, grandiose wall cycles. Justinian's palace was decorated with mosaics depicting the emperor's triumph over the Goths and Vandals. Pictures of battles and portraits of the imperial family were depicted in the mosaics of the Cainurgion, the luxurious palace of Basil the Macedonian. Secular painting, apparently, became especially widespread in the era of the Komnenos. The Blachernae palace of Manuel Komnenos was painted with frescoes and decorated with mosaics depicting scenes from history and modern times. On the walls of the residence of Andronikos Komnenos his entire biography was written - the whole story of his hunting, wandering life, full of all sorts of adventures. The Byzantine nobility imitated the example of the emperor in their palaces of Constantinople, in their villas on the banks of the Propontis. Diehl cites a very characteristic passage from a chronicler telling about the nephew of Emperor Manuel, who, wanting to decorate his house with paintings, "n"y representa ni les episodes de la mythologie grecque, ni les exploits de l"empereur comme c"est l"habitude de gens haut places, ni ce que lui-meme avait accompli a la guerre ou a la chasse"... This passage gives a very valuable hint at the established and generally accepted secular character of the paintings of the Byzantine palace of the 12th century. Moreover, a huge, perhaps irreparable gap is the complete absence of Byzantine secular paintings in the historical material that we now have and on the basis of which we are trying to build the history of Byzantine art. We must consider the disappearance of the palaces of Constantinople from the face of the earth not only as a significant quantitative loss. Along with them, an entire branch of Byzantine painting disappeared, living its own special, large and full life. She is unknown to us. Consequently, its relationship with the only painting of the “church” that is currently accessible to our study is also unknown, its influence on this painting is unknown, regarding which we can now only guess that in some eras they were decisive,

It is to be hoped that fundamental changes in the cultural situation of the state, which still owns the shores of the Bosphorus, will facilitate the work of historians of Byzantine art in that area, which remains and will remain, of course, the most important. In recent years, among those involved in Byzantine artistic history, the balance of research attention has been clearly upset in the sense of the predominance of interest in the original period, in the period of origin, which has taken historians too far to the East from the capital of the Empire - to Syria, to Mesopotamia, to Armenia. In even more recent years, thanks to the works of mainly French historians, this balance was somewhat restored by a new assessment of the last period of Byzantium. The attention of researchers attracted by the 14th century revealed the significance of the paintings of Mystras, Athos, and Serbian and Russian churches of this period. Then followed the most interesting discoveries of frescoes and icons of the 12th century in Russia, and we are now witnessing the deepening of interest in Byzantine XIV century resurrects the Byzantine XIII and XII centuries, just as the Byzantium of the Palaiologos finds an explanation for itself in the Byzantium of the Komnenov. And at the same time, the circle of historical searches is narrowing around Constantinople. Bulgaria and Macedonia come to the forefront of our attention, which is quite natural, due to their proximity to the capital. The work of the Bulgarian scientist A. Grabar on the churches of Boyana and Tarnova (XIII century) and the work of the Russian scientist N. Okunev in the Nerez monastery (1164) and in a number of other churches on the territory of the present Yugoslav kingdom are a great contribution to the history of Byzantium.

When will they be published? latest works Bulgarian, Russian and Serbian scientists now working in the countries of the Balkan Peninsula, our understanding of the era of the last Komnenos and the first Palaiologos will undoubtedly be very different from that which was available to historians who knew of all this brilliant period only the mosaics of the Chorus (Kahrie-Jami) . But, unfortunately, it is very unlikely that in the territory of young Slavic states, who actively took up historical work only after the war, monuments of painting from an older period will also be revealed along the way - that quarter of a millennium (900-1150), which marked precisely the era of the greatest political power of the Empire. Associated most of all with the heyday of the capital of the Empire, this era could only be illuminated by new artistic discoveries within the walls of Constantinople itself and in its immediate surroundings on the European and Asian shores. There is no doubt that these discoveries are only a matter of time. Anticipating their possibility, we cannot help but foresee, however, that even in the best case they will still appear scattered, united in the attention of the researcher only by the whim of time and the arbitrariness of historical fate. With all the vicissitudes of this fate that the shores of the Bosphorus experienced, one cannot count on the scientist’s diligence and happiness to resurrect there

any complete picture of the thousand-year life of Byzantine art. The Christian East introduces us only to the most ancient periods of this art; the Slavic countries, on the contrary, reveal only later eras; the area of Constantinople remains inaccessible for serious study. Under such conditions, the study of Byzantine monuments and Byzantine influences in Italy acquires a special and very important role.

Italy is still the only country where all eras of Byzantium are represented by works of Byzantine masters or completely clear influences of Byzantine art. Only in Italy will we find an almost continuous series of monuments of painting, going from the time of its origin to the last period in its development - from the 4th century to the 14th. Only here can we see the overall picture of her thousand-year life - even if it is far from a complete picture and not equally instructive in all parts, and yet integral, which we will not see in any other country.

It would seem completely idle to argue about what percentage of Byzantine mosaics and paintings in Italy were performed by Byzantine masters and what percentage were done by Italians who worked in the system of Byzantine art or were entirely under its influence. When a similar question was posed regarding mosaics and frescoes of the 11th, 12th and even 14th centuries in Russia, it could presumably be resolved there in the sense of the predominance of visiting masters over Russians on the basis of the cultural youth of medieval Russia. In Italy this basis disappears, and the general Hellenistic subsoil here speaks rather in favor of the strength of the local artistic traditions of style and quality. Not only all those mosaics and frescoes that we define as “bizanti-neggianti,” but even many purely Byzantine monuments in Ravenna, Rome, and Venice were, in all likelihood, executed by masters of Italian origin. And this still does not change the essence of the matter at all, since the Italian masters in such cases worked without going beyond the boundaries of the Byzantine art system in any significant way. Their frescoes or mosaics remained Byzantine painting.

In Italy, Byzantine art had to overcome the traditions of local Roman-Hellenistic art during the period of its origin. In the era of the deep Middle Ages, Byzantinism was interpreted here not without the influx of fresh “barbarian” forces that the West provided and which the East, conquered by Islam, could no longer provide. Later, in the 11th and 12th centuries, Italy uniquely combined the work of Byzantine masters with the work of the creators of Romanesque art. In the second half of the 13th century, a new tide of Byzantine influences turned out to be most fruitful for the birth of Italian art, which showed its genius precisely in the fact that, born at the moment of the meeting of Byzantium and Gothic, it became neither a Byzantine branch nor Gothic, but immediately gave a special, national life the mighty trunk of the Italian Renaissance. In all such cases, on the soil of Italy, Byzantine art collided, intertwined, and struggled with the form and spirit of other artistic systems. Such a phenomenon could not, of course, take place either in the Slavic countries, deprived of an ancient cultural tradition, or in the countries of the East, which did not know the influx of fresh forces of Western “barbarian” life. In Russia and Serbia, in Georgia and Armenia, in Syria and Cappadocia, Byzantine art, which arrived there at different periods, immediately took possession of the situation and dominated there exclusively. And even in those cases when, as apparently happened with the architecture of Armenia, it encountered local national forms, it introduced them into its system, depriving them of local national significance, and already in an “imperial” order, passing them through Constantinople, distributed them everywhere and often returned them as an “imperial” gift to the very provinces from which it borrowed them.

Only in Italy do we see Byzantine art in sharp comparison and contrast with other arts, and if this sometimes disrupts the harmony of individual impressions and leads to such intricate complexes as the mosaics of San Marco, about which there are no two identical opinions in countless reviews of historians, then are felt nowhere with such clarity as in Italy, character traits Byzantine art in contrast to the features of its neighboring arts. Only in Italy, without going beyond Ravenna, can one see excellent examples of the replacement of Roman-Hellenistic painting with Byzantine painting. Only in Italy are Romanesque paintings of the Benedictines adjacent to Byzantine on the walls of Sant'Angelo in Formis. Only in Italy can one observe the first painters of the Renaissance - Cavallini, Duccio, Giotto, very close to the mysterious neo-Hellenistic outbreak that illuminated the decline of Byzantium.

And despite this, which becomes more and more obvious to us every year, bringing new discoveries, the predominant

the significance of Byzantium itself in the history of Byzantine creativity, despite this great vitality of Constantinople art, even at the end of the Empire, which was transferred by the sailors of Pisa, Genoa, Venice to the soil of Italy and here was able to make an impression on the nascent national art no less strong than the French Gothic of the era its heyday - despite all this, one can still find to this day intentions to deny the unity called “Byzantine art” - to deny even the right for works of art medieval Christian East to be called "Byzantine". Strange as it may seem, historians of Byzantine art have to first prove that Byzantine art existed at all...

This reflects, on the one hand, the difficult situation in which Byzantine art placed historians with its unprecedented expansionism. Having spread to geographically distant territories of the West and East, North and South, overcoming the deepest differences in natural conditions, creating a common artistic language for the most diverse nationalities, tribes and even races, this art could not, of course, help but vary depending on the conditions of the place , time, life and character. It could not help but reflect, to some extent, the vital or spiritual traits of the people who were wholly or at least partially captured by Byzantine civilization. But at the time when Byzantium perished, these peoples remained alive. Some of them formed nations that created independent cultures. Turning to your ancient history, these nations saw Byzantium there, but preferred to include its creation in their national legend. This is how denials of Byzantine artistic “hegemony” arose among historians of Russian, Bulgarian, Armenian, Serbian and even Georgian, even Romanian art. As for Italy, which, of course, least of all needed confirmation of its artistic independence in this way, here too there was a desire to reduce the role of Byzantium to zero or, worse, to some kind of negative minimum. Even capital investments are not partly free from this trend. modern works Venturi and Van Marle, not to mention individual articles and monographs, where even the Ravenna mosaics almost completely deny their belonging to Byzantine art. Fortunately, the famous new general work Toesca restores the damaged historical perspective in this sense.

Another circumstance that contributed to the violation of “historical justice” not in favor of Byzantium was the predominant attention that over the next decades was given to the period of origin of Byzantine art. In this area, much has been achieved compared to the ideas that lived in the 19th century. It can be considered, for example, that it has been conclusively proven that the main role in the origin of Byzantine art it belongs to the Hellenistic East, which in turn preserved and passed on to Byzantium many traditions of the Ancient East. It can be considered proven that during the period of its origin, Byzantine art was formed in Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch more than in Constantinople, and that its elements arose earlier in Syria, Palestine, Asia Minor and Italy, earlier than in the southeastern extremity Balkan Peninsula. The capital of Byzantium was not the cradle of Byzantine art. In this case, is it correct to give the name of Byzantium to the arts that first came to life almost always far from the Byzantine capital, and is it not more fair, as Dalton did in his last book, to give them the more general name of the arts of the “Christian East”? Historians who were primarily concerned with the origins of Byzantine art had an understandable desire to extend the methods and conclusions of their research to later periods of Byzantine history. If Constantinople of the 4th and 5th centuries was only a receiver, where various artistic forms created in separate parts of the vast Empire flocked, then could not this phenomenon continue and be repeated in subsequent centuries? Thus, Strzygowski was inclined to explain the entire development of Byzantine architecture in the 6th-9th centuries by a simple transfer to Constantinople of forms created in Asia Minor and especially in Armenia. Byzantine artistic history, viewed from this angle, seemed to be in a state of “permanent origin.” The fascination with the creative role of the East was sometimes so great that many phenomena that were much more natural and easier to explain as phenomena of life and growth in Byzantine art were interpreted by a completely fantastic appeal to Eastern models almost a thousand years ago. This is how the famous “Syrian” theory of Strzygowski arose for the explanation of the “Serbian” Psalter, which does not need such an artificial explanation at all now that we know the 14th century better and find a completely legitimate place for the miniatures of this manuscript next to the numerous icons and frescoes of this era.