What is the general specificity of the epic of the mature Middle Ages in comparison with early medieval epic poetry?

The epic of the mature Middle Ages, in contrast to the epic of the early Middle Ages, is usually called heroic knightly epic. The epic of the mature Middle Ages was already taking shape when feudal relations were formed, when chivalry was being constructed, when a complex hierarchy of lords and vassals took shape. New character images are associated with this. With all the abundance of characters in the epic of the mature Middle Ages, they are all knights, not just warrior-heroes, but certainly knights, and noble ones, people belonging to a privileged class.

So, Roland is one of the nephews of Charlemagne and one of the 12 peers of France. Siegfried - Prince of the Netherlands. Sid, however, is a lowly knight in the poem (but historically this was not the case) - this is a democratization of the image of Sid. She is bound as a result of the Reconquista. Large sections of the population took part in it, and this is what is associated with the democratization of epic consciousness in Spain. But Sid is still a knight. And Roland, and Siegfried, and Sid - folk heroes, they are universal in their thoughts, feelings, actions and goals. The authors endow the heroes with a high rank in order to depict complete freedom of action.

The epic of the early Middle Ages is imbued with pagan ideas, and the epic of the mature Middle Ages takes shape when Christianity is introduced throughout the world and shapes the entire culture. Therefore, Christian motifs in the epic are used to glorify characters. The knights have the gift of tears, which came here from early Christian literature, the heroes shed tears. Charlemagne sheds tears over Ganelon's insidious plan.

In “The Song of Roland,” Christian motifs are used especially widely; Roland is portrayed as a vassal not only of the king, but also of the Lord God, to whom he extends the glove before his death. This gesture is very important for the affirmation of the immortal Roland principle.

There are also differences between the heroic epic and the earlier epic, reflecting the specifics of the changed consciousness. Historical reality begins to come first, and not hide behind myth and fairy tale. Knights do not fight with mythological monsters and giants, they fight with real historical opponents - the Moors, the Huns. They operate in a real historical and geographical context, and they have real historical and political goals: They serve Charlemagne, they serve Alphonse the Sixth. The division of the world into friends and foes, characteristic of the epic consciousness, is preserved, but it is projected onto a completely real historical basis. Moreover, in the epic the image of the struggle with an external enemy is combined with the image of internal conflicts - feudal strife, for example. At the center of the conflict is very often a clash between norms of behavior associated with real court practice and ideal folk ethical norms. The character's worth is assessed from the latter's point of view.

There are also genre differences. The early medieval epic is characterized by a small genre - the genre of a small epic song, the genre of a short prose narrative. At the same time, there are few characters, the composition is simple. In the epic of the mature Middle Ages, the poems are large, there are many characters, and the plot organization is complex.

Specifics of the image of personality in the epic of the mature Middle Ages. Previously, characters were characterized by psychological undevelopment; the emphasis was placed not on the image, but on the situation. But in the mature Middle Ages this is no longer the case: the idea of personality and its self-worth is more developed, and therefore the images of heroes and the relationships between them are depicted more fully by means of art.

Let's take, for example, the main characters of three poems: Roland, Siegfried, Sid. Their characteristics achieve noticeable individualization. They, of course, express people’s ideas about heroes, but each one is individual. Surrounded by a fairy-tale aura, Siegfried, brave Roland, practical Sid. Or, for example, Roland and Olivier: they are opposites. “Olivier is wise, and Count Roland is fearless.” The narrator contrasts Olivier's wisdom and sanity with Roland's insane courage. This had never happened before in poetry: one hero differed from a hero only in the degree of expression of certain heroic qualities.

There is great character development in terms of developing the motif of tragic guilt, which plays a large role in all three songs. In "Song of My Sid" this motif is weakened compared to the other two songs. The motive of Sid's tragic guilt is expressed in the episode when Sid, intoxicated by the victory over the Moors, exclaims that everyone is bowed to him, he is overwhelmed with pride. The motive is not very pronounced.

Now a few words about the storytellers. It must be said that even in the mature Middle Ages, the storyteller combined the functions of both performer and creator. But his position changed: he became a traveling singer, that is, a singer of the whole people. He also went to knight's castles, and to monasteries. Most often, storytellers performed epics during fairs in the city square. In connection with the performance of the heroic epic orally, in chant, some of its poetic features are associated. The storytellers accompanied their story with an accompaniment to musical instruments- harps, violas.

At that time, the verse was not yet fully formed, the stanza was unclear. The narrator in one breath pronounces what is called a tirade in prose, and then was called a lessa. The number of lines in it varied. As the epic progresses, it comes to a certain stanza - for example, the four-line stanzas in the "Song of the Nibelungs".

In languages of Romance origin, the connecting link that united lines into one stanza was consonance of vowels - that is, assonance, and in languages of Germanic origin such a role was played by consonance of consonants, that is, alliteration. In all cases, a tendency to order the poetic lines developed. But the verse still remained archaic, which was expressed in the presence of a “stumbling” line, especially present in the “Song of the Nibelungs.”

There were other features as well. For example, the word "Aoi" at the end of almost every loess in The Song of Roland. Some believe that this is an interjection, while others believe that it is a truncated form of the word “Montjoie,” the victory cry of Charlemagne. The third assumption is that “aoi” is a remnant of the motive to which it was customary to sing the song. The melody was indicated using letters, but there were no notes.

"The Song of Roland"

This is the pinnacle of the development of medieval heroic poetry. The French epic is rightly considered the most developed and well preserved. It has come down to us in the form of large poems, the number of which is approaching a hundred, they are called “Songs of Deeds.” According to tradition dating back to the 13th century, songs are divided into three directions - royal and two baronial. The Song of Roland belongs to the royal cycle. The oldest edition was formed at the end of the 11th - beginning of the 12th century; it came to us in the list of 1170. The list was called Oxford after the place where it was found, and the edition is also called Oxford.

The images and motifs of this work were extremely popular not only in the Middle Ages, but also in later eras until the 12th century. The most interesting images and motifs of the poem were not only used to express patriotism, they were used in the 20th century to express existentialism. For example, Marina Tsvetaeva wrote a poem about Roland. These images have become the universal language of art.

Let's start with the relationship between history and fiction. Like any heroic epic of the mature Middle Ages, the song has a completely real historical basis. This is Charlemagne's campaign in Spain in 778. This year, Charles decided to intervene in the discord of the Spanish Moors, he crossed the Perenea and besieged Zaragoza, because some emir told Charles that Zaragoza would become his easy prey. But she did not become an easy prey, the siege dragged on, and news came from the east of Charlemagne’s empire that the Saxons had rebelled there, and Charles decided to lift the siege. When Charles's army was returning to their homeland and crossing the Perenean Mountains, the rearguard of his troops was attacked by the Moors and Basques. We know about this from Einhard's chronicle.

This real historical event was reflected in the poem, but subjected to glorification and stylization. What’s interesting is that the poem had a second historical basis - the reality of the late 11th - early 12th centuries, that is, when the Oxford edition of the song took shape, because the spiritual atmosphere of that time determined the nature of the interpretation of the event, its pathos, mood. The circumstances that determined the specifics of the spiritual life of France in the 11th-12th centuries were the greatest chaos and anarchy that reigned then. France reached the highest point of feudal fragmentation. The king was only a figurehead; his dukes and counts were often stronger than him. In the sphere of consciousness, a reaction to this fragmentation began to take shape in the form of a craving for unification, a craving for a monarchy around which all national forces could rally.

Hence the exaggeration of the size and power of Charlemagne, the image of this empire as a powerful state, the idealization of Charlemagne. He appears as the ideal epic king: he rules over a vast territory, his peers and barons serve him faithfully and devotedly, he is majestic and gray-bearded, wise with years and experience. He is 200 years old. In fact, he was only 36 years old at the time and never wore a beard, only a small mustache.

In connection with the image of Charles, the short and unsuccessful campaign in the song is transformed into a victorious seven-year war, which ends with the conquest of Spain. Only Zaragoza did not submit, and that was not for long.

Also, the peculiarity of the spiritual atmosphere of France explains the theme of condemnation of feudal self-will, the bearers of feudal discord, running through the entire work. Such a carrier in the poem is Ganelon. It is because of him that the disaster happens. Also at that time, the sentiments associated with the preparation of the first crusade to Jerusalem with the aim of liberating the Holy Sepulcher were relevant. In general, the literature of the 2nd century is permeated with the theme crusades, to the point that they even came up with a special genre for this.

So the second cross-cutting theme of the work is national-religious, and the dualization of the world associated with this theme. The whole world is divided into Christian Franks and pagan Moors. The pagans had to either be killed or converted to Christianity.

The national-religious theme gives rise to the second hypostasis of Charles. He is a stronghold Christendom, a kind of embodiment of the very spirit of the Crusades, he is given power.

In addition, there is a parallel to the national-religious theme that runs through the entire poem and includes its events in common system Christianity. The story of Charles, the 12 peers and one traitor Ganelon shares a biblical theme with the parable of Jesus, the 12 apostles and one traitor Judas. At times, the traits of a martyr appear, while at the same time being submissive to fate. When Karl sheds tears, it is as if he cannot do anything, although he can even foresee the future. When he understands Ganelon's plan, he begins to cry instead of doing anything.

A combination of national-religious themes and the theme of condemnation of feudal strife. The presence of two themes in the work determines its rather complex structure and the presence of two plots. The first is the embassy of Blancadrin, whom Marsilius sends to Charles to gain time. He promises to be baptized in Aachen on St. Michael's Day (in reality, this is a trick to convince Charles to leave Spain and wait for reinforcements). The second is the place where the choice of who will carry out the return embassy takes place. This is the main plot; it is the one that will predetermine the course of events. Peers and barons gather around Charlemagne to decide who will go. Roland's stepfather, Ganelon, will go. True, he thought that Roland nominated him as ambassador in order to destroy him. He appears before us as a person wholly normalized by the prevailing ideas about court practice. The logic of his reasoning: the embassy is dangerous, the Moors have already killed two ambassadors. On the other hand, he and Roland are in no way inferior to each other, and in such a situation Roland should not nominate Ganelon, and if he did, it means he wants to kill. Ganelon openly declares that Roland is his enemy and he will take revenge. Announces enmity to Olivier and all the peers who love Roland.

If you look at his behavior from the point of view of the norms accepted in court practice, then it is impeccable. But he causes antipathy. At the end of the episode, he accepts the staff and gloves from Karl, symbols of an ambassador, and he drops them. A very important detail.

Bottom line. Despite the importance of the national-religious theme in the work, the dominant line is the condemnation of feudal fragmentation.

Despite the dualization of the world, the Christian Ganelon turned out to be a traitor, so that the principle of moral division of people was superimposed on the division. He still expresses himself weakly, not like in “Song of My Sid.” Cid is generous to the conquered Moors, no intolerance. And the Moors love him. The main event is the assault on Valencia.

In the Middle Ages, the Lives of the Saints, which described the life and religious exploits of Benedict of Nursia, Francis of Assisi and other Christian saints, were extremely popular.

People of the Middle Ages also loved to read and listen to works heroic epic. These were tales of battles and heroes, fairy-tale princesses and terrible monsters. For example, in famous poem "The Song of Roland" it was told about the courageous count and his valiant detachment, which covered the retreat of Charlemagne’s army from Spain. The entire detachment dies in an unequal battle with the Muslims, but does not give up and does not ask for mercy. Only Roland remains alive, having accomplished incredible feats.

With your formidable sword Durendal he destroyed crowds of infidels. All wounded, the count blows the horn, calling for help from his king. But the lord's troops are already too far away. Mortally wounded, Roland tries to break his faithful sword on the stones so that the enemy does not get it, but the glorious sword in his hand only crumbles granite:

The count felt that death had overtaken him, I got to my feet, gathered the rest of my strength, He walks, although there is no blood on his face. He stopped in front of a dark block. He hit her ten times angrily. The sword rings on the stone, but does not chip The Count says: “Mother of God, help me, It's time for us, Durendal, to say goodbye to you. You and I have beaten many enemies, With you big lands conquered. A cowardly enemy should not own you..." The count sensed that death was coming to him, Cold sweat streams down your forehead. He walks under a shady pine tree, Lying down on the green grass. He places his sword and horn on his chest. He turned his face to Spain, So that King Charles can see When will he and his army be here again? That the count died, but won the battle.With bated breath, people listened to the story of the brave and noble knight. Roland became a model of loyalty and honor for many generations of medieval knights.

In the 12th century the first chivalric novels. The most famous of them is "The Tale of Tristan and Isolde". Tristan, a valiant knight “without fear or reproach,” a devoted vassal of his king, fell in love with his bride, the beautiful Isolde. And she fell in love with the beautiful knight. But Tristan could not break his oath of allegiance to the king and decided to retire overseas. There he was mortally wounded. Before his death, Tristan sends for Isolde, dreaming of seeing her for the last time. In order to recognize her ship from afar, he asked to raise white sails on it. Isolde hit the road. All the way she stood on the bow of the ship, peering into the foggy distance. The minute of the long-awaited meeting of the lovers was already close. However, one insidious lady, out of jealousy, told Tristan that the sails on the approaching ship were black. Considering that his beloved is not on the ship, he dies of grief. Isolde, quickly escaping from the ship to the shore, sees the lifeless body of her lover and falls dead next to her.

The romances of chivalry reflect the eternal dream of man about high and devoted love, for which there are no barriers and distances. But at the same time, the novels glorified loyalty to the lord as a symbol of the highest valor for a knight. Material from the site

There was another literary genre that was very popular in the Middle Ages - urban romance. The most famous work of this genre is "Novel about the Fox". In it, typical representatives of medieval society were presented under the guise of animals. A large lord is a Bear, an evil and greedy feudal lord is a Wolf, an intelligent and resourceful city dweller is a Fox. The fox is cunning and resourceful. In a fight with the Wolf, he always comes out victorious. The novel was read not only by townspeople, but also by representatives of all classes. The urban romance fostered a sense of human dignity and condemned the habit of breaking one's hat in front of the nobility.

Medieval European culture was closely connected with the Christian religion. She instilled in believers the renunciation of everything earthly and physical, and instilled in them that earthly life- only preparation for heavenly life. At the same time, literary works are already appearing that instill a sense of self-worth in a person.

On this page there is material on the following topics:

Culture of Western Europe in the Middle Ages literature

Messages on the topic of chivalric literature

The heroic epic of the Western European middle class

Heroic epic summary summary

Report on the topic of knights, knightly culture briefly

Questions about this material:

Middle Ages: Romanesque and Gothic, heroic epic and chivalric romance, Dante and Giotto

The Middle Ages is a long period of world history, stretching from the end of the 5th century. to the 15th century, connecting antiquity with the Renaissance. The beginning of medieval history is conventionally considered to be 476, when the final fall of the Roman Empire took place as a result of numerous uprisings of slaves and uprisings of the plebs, as well as under the onslaught of barbarian tribes that invaded the north. Apennine Peninsula. The end of the Middle Ages was the Renaissance of ancient culture, which began in Italy from the middle of the 14th century, and in France - from the beginning of the 16th century, in Spain and England - from the end of the same century. The Middle Ages were characterized by the dominance of the Christian religion, asceticism, the destruction of ancient monuments, and the oblivion of humanistic ideas in the name of religious dogma. From the end of the 4th century. Christianity became the state religion, first in Rome, and then in the emerging barbarian states, for the leaders of the Germans, Franks, and Celts soon realized that the ideas of monotheism contributed to the elevation of their authority among their fellow tribesmen. Having mastered and processed Latin, they accepted baptism and the dogmas of the church.

French historian Jacques le Goff characterizes the mentality of medieval man in the following way: “Of course, in the early Middle Ages, the immediate goal of human life and struggle was earthly life, earthly power. However, the values in the name of which people then lived and fought were supernatural values - God, the city of God, paradise, eternity, disregard for the vain world, etc. (a typical example is Job - a man slain by the will of God). The cultural, ideological, existential thoughts of people were directed towards heaven.”

Worldly life was neglected in the name of eternal bliss in the other world. However, human nature gradually took its toll. If in the early Middle Ages the body was despised, and the carnal principle was supposed to be humbled and curbed, then gradually the bodily shell was recognized by the clergy as the abode of a spiritualized being, and the beauty of the body meant the beauty of the soul.

Reason was not forgotten either. In the Middle Ages, many discoveries and inventions were made, including gunpowder, alcohol, horse harness, glasses, women's and men's clothing, which have retained the main structural elements to this day. Clothing is cut to fit the figure, fits closely, and matches the lines of the body. Such clothing details appear as bodice, sleeves, skirt and trousers, hoods, gloves, boots.

Alchemy played an important role in the study of the properties of metals, the passion for which came to Europe along with the Arabs at the beginning of the 9th century. Alchemists tried to convert base metals into noble ones by adding a special substance, which they called the philosopher's stone. At the same time this philosopher's Stone, also called the great elixir, magisterium, vital panacea, was supposed to act on human body as a universal medicine, relieving a person of all diseases and restoring youth to the body, whoever found the philosopher's stone was considered an adept. However, none of the alchemists actually succeeded in turning base metals into gold. But alchemy was a kind of predecessor of chemical science.

The general passion for astrology, so characteristic of the Middle Ages, contributed to the development of astronomy. Trying to predict the fate of a person or the onset of social disasters by the movement of the planets, astrologers placed the planets in 12 parts of the zodiac, which later helped in the compilation of the celestial globe.

Finally, it was in the Middle Ages that literary genres arose that still exist today: the novel, sonnet, ballad, madrigal, canzone and others.

At the end of the Middle Ages, great geographical discoveries occurred and printing was invented, cities were revived and universities were opened.

Middle Ages in historical process until recently it was interpreted as a decline in art and literature - now this view seems outdated. In the Middle Ages, verbal and plastic arts had their own specific feature - anonymity. In most cases, it is impossible to name the author of the works. They were created by a collective folk genius, as a rule, over a long period of time, often over several centuries, through the talent and dedication of many generations. Another characteristic feature medieval literary monuments, there was the presence of so-called “wandering stories”, due to the fact that epic songs were spread orally, they gained recognition among different peoples inhabiting Europe, but each nation introduced original details into the stories about the exploits of heroes, interpreted the heroic and moral ideal.

The leading genre of medieval literature were epic poems, which arose at the final stage of the formation of nations and their unification into states under the auspices of the king. Medieval literature of any nation has its roots in extreme antiquity. Myths and historical facts, legends and stories about miracles and exploits over many generations are gradually synthesized into a heroic epic, which reflects the long process of formation of national self-awareness. The epic forms the people's knowledge of the historical past, and the epic hero embodies the people's ideal idea of themselves.

In the epic tales of the Middle Ages, the loyal vassal of his overlord always plays a very important role. This is the hero of the French “Song of Roland”, who did not spare his life to serve King Charlemagne. He, at the head of a small detachment of Franks in the Roncesvalles Gorge, repels the attack of thousands of Saracen troops. Dying on the battlefield, the hero covers his body with his military armor, lies down facing the enemies, “so that Karl would tell his glorious squad that Count Roland died, but won.”

Roland is the hero of numerous songs about robes, the so-called chansons de geste, performed by folk singers called jugglers. They probably did not mechanically repeat the lyrics of the songs, but they often contributed something of their own. The lyrics were divided into separate tirades, each of which ended with the exclamation “Aoi!” This indirectly indicates that the Song of Roland was sung by jugglers. At the base of the monument folk poetry based on historical events, significantly rethought. In 778, the king of the Franks, Charles, made a campaign beyond the Pyrenees for rich booty. The Frankish invasion lasted several weeks. Then Charles's army retreated, but the Basques attacked the rearguard in the Roncesval gorge, commanded by the king's nephew Hruodland. The forces were unequal, the Frankish detachment was defeated, and Hruodland perished. Charles, returning with a large army, avenged the death of his nephew.

Folk storytellers gave an exceptional character to everything that happened.

The short campaign turned into a seven-year war, the goal of which, as interpreted by the jugglers, became extremely noble: Charles wanted to convert the unfaithful Saracens to the Christian faith. The king has aged considerably; the song says that the gray-bearded old man is two hundred years old. This emphasizes his greatness and nobility. Saracens were the collective name for the Arab tribes that invaded the Iberian Peninsula.

They were Muslims, not pagans. But for the storytellers they were simply non-Christians who should be guided on the path of true faith.

Hruodland became Roland, but most importantly, he acquired exceptional heroic power. Together with his companions: knight Olivier, Bishop Turpin and other brave knights, he killed thousands of enemies on the battlefield. Roland also has extraordinary battle armor: the sword Durendal and the magic horn Oliphant. As soon as he blew the horn, the king, wherever he was, would hear him and come to his aid. But for Roland it is the greatest honor to die for the king and dear France. His patriotism contrasts with the betrayal of his stepfather Ganelon, who entered into a vile conspiracy with the opponents of the Franks.

The Song of Roland took shape over almost four centuries. The real details were partly forgotten, but its patriotic pathos intensified, the king was idealized as a symbol of the nation and state, and the feat in the name of faith and people was glorified.

The characters in the poem are highly characterized by their belief in immortality, which the hero gains through his heroic deeds. It is curious that in Europe a tradition arose everywhere of installing a sculpture of the mighty Roland leaning on his sword on the facades. The knight was perceived as the protector of the home from all foreign enemies.

Ruy Diaz de Bivar, nicknamed Cid, is also faithfully serving his king Alfonso VI, the hero of the Spanish folk epic “The Song of Cid,” who liberated Valencia and other Spanish lands from the Arab tribes that had captured them.

The ideology of feudal society required the vassal to unconditionally carry out the will of his overlord. The duty of Roland and Cid is unquestioning obedience to the king.

The beginning of the “Song of the Cid” (XII century) was lost, but the exhibition told that King Alfonso was angry with his faithful vassal Rodrigo, nicknamed by the Arabs Cid, which means lord, and expelled him from the borders of Castile. Folk singers - in Spain they were called juglars - emphasize democracy in their favorite, and the reason for the royal disfavor was the envy and slander of the nobility.

Despite his unjust anger, Sid remains a loyal servant of the king. Conquering new lands from the Arabs, Sid each time sends part of the tribute to the king and thereby gradually achieves forgiveness.

The image of Sid captivates with its realistic versatility. He is not only a brave commander, but also a subtle diplomat. When he needed money, he did not disdain deception; he cleverly deceived gullible moneylenders, leaving them chests with sand and stones as collateral. Sid is having a hard time with the forced separation from his wife and daughters, and when the king betrothed them to noble swindlers, he suffers from the insult and calls out for justice to the king and the Cortes. Having restored the honor of the family and gained royal favor, Sid is satisfied and marries his daughters a second time, now to worthy grooms.

The epic hero of the Spanish epic is close to reality, this is explained by the fact that “The Song of Cid” arose just a hundred years after Rodrigo accomplished his exploits. In subsequent centuries, the Romansero cycle arose, telling about the youth of the epic hero.

According to the definition of the outstanding scientist Academician V.I. Zhirmunsky: “The epic represents the historical past of the people on the scale of heroic idealization.” Indeed, in the epic tales of different peoples, an ideal portrait of a knight has been recreated, which most fully and comprehensively expresses the ideas of devotion to serving the national idea; the service itself has a religious connotation, for even the shape of the sword and the cross are similar. Such is the hero of German epic tales - Siegfried.

The German heroic epic “The Song of the Nibelungs” was written down around 1200, but its plot dates back to the era of the “Great Migration” and reflects the real historical event: the death of the Burgundian kingdom, destroyed by the Huns in 437. But the Nibelungen heroes have even more ancient origins. The Scandinavian monument "Elder Edda", reflecting the archaic Viking era, features such heroes as Sigurd, Gunnar, Högni, Kudrun. The sound of the names and the trials they endured are reminiscent of the main characters of “The Song of the Nibelungs”: Siegfried, Gunther, Hagen and Kriemhild. However, the Scandinavian and German heroes also have significant differences. In the Edda, the events are mainly mythological in nature, while in the Song of the Nibelungs, along with myths and legends, history and modernity are reflected. In particular, the courtly poetry of the 12th century left its mark on the German heroic epic with its cult of the beautiful lady and the motive of the love of a knight who had never seen her, but was inflamed with passion for her only because rumor glorified her beauty and virtue throughout the land.

Due to the fact that “The Song of the Nibelungs” was formed over several centuries, its heroes act in different time dimensions, combining in their minds the daring of valiant deeds with the observance of courtly etiquette.

“The Song of the Nibelungs” is one of the most tragic creations of world literature. Cunning and intrigue lead the Nibelungs to death.

The tragedy of all the Nibelungs begins with the death of an epic hero, which is Siegfried - the ideal hero of the “Song of the Nibelungs”. The prince from the Lower Rhine, the son of the Dutch king Siegmund and Queen Sieglinde, the conqueror of the Nibelungs, who took possession of their treasure - the gold of the Rhine, is endowed with all the virtues of knighthood. He is noble, brave, courteous. Duty and honor are above all for him. The authors of the “Song of the Nibelungs” emphasize his extraordinary attractiveness and physical strength. His very name, consisting of two parts (Sieg - victory, Fried - peace), expresses the national German identity at the time of medieval strife.

The first seventeen adventures (chapters) are devoted to the fate of Siegfried. He first appears in the second adventure, and the mourning and funeral of the hero takes place in the seventeenth adventure. It is stated about him that he was born in Xanten, the capital of the Netherlands. Despite his young age, he visited many countries, gaining fame for his courage and power. Siegfried is endowed with a powerful will to live, a strong belief in himself, and at the same time he lives with passions that awaken in him by the power of foggy visions and vague dreams.

Having undergone the rite of knighting, solemnly celebrated together with four hundred peers, Siegfried decides to leave his father’s house and go to Worms, the capital of the Burgundians, to test himself so that the self-realization of the individual can occur. In addition, he is forced to set off on a journey by the desire to marry Kriemhild, rumor of her beauty has spread throughout the world. In this desire to connect one’s fate with one he has not seen, the traditional motif of “love from afar” for courtly poetry is manifested, but one can see in this very real circumstances, since dynastic marriages in the Middle Ages were often concluded without preliminary meetings.

The image of Siegfried combines the archaic features of the hero of myths and fairy tales with the behavior of a feudal knight, ambitious and cocky. Offended at first by the insufficiently friendly reception, he is insolent and threatens the King of the Burgundians, encroaching on his life and throne. He soon resigns himself, remembering the purpose of his visit. It is characteristic that the prince unquestioningly serves King Gunther, not ashamed to become his vassal. This reflects not only the desire to get Kriemhild as a wife, but also the pathos of faithful service to the overlord, invariably inherent in the medieval heroic epic.

Siegfried plays a major role in Gunther's matchmaking with Brunhild. He not only helps him defeat a mighty hero in a duel, but also gathers a squad of thousands of Nibelungs, who must accompany the bride and groom returning to Worms. The powerful Burgundian ruler sends Siegfried to the capital city with the good news that he has mastered the warrior maiden, so that his relatives prepare a solemn meeting for them. This causes the heartfelt joy of Krimhilda, who hopes that the messenger can now count on marrying her. A magnificent double wedding took place.

Kriemhild gave birth to an heir to Siegfried, who was named Gunther in honor of her older brother.

After ten years of separation, Siegfried and Kriemhild receive an invitation from Gunther and Brunhild to visit Worms. The Nibelungs go to visit, not knowing what trouble awaits them there.

The quarrel between the two queens turned into disaster for Siegfried. Having learned from Kriemhild that Siegfried, having bathed in the blood of a dragon, had become invulnerable to arrows, their faithful vassal Hagen realized that the hero had his own “Achilles heel”: a fallen linden leaf covered the body between the shoulder blades, this is what poses a danger to the brave knight . The traitor kills Siegfried while hunting, throwing a spear at the unarmed hero leaning over a stream, aiming between the shoulder blades. The blow turned out to be fatal.

With the death of Siegfried, the narrators' attention is focused on the fate of his widow, who takes bloody revenge on her relatives for the death of her husband.

Kriemhild uses Etzel's matchmaking and then marriage with the king of the Huns exclusively to carry out her bloody plans. The compositional structure of “The Nibelungenlied” is symmetrical, and the characters repeat each other’s actions. So, Kriemhild persuades Etzel, as Brunhild had previously begged Gunther, to invite his brothers to visit him in order to inflict reprisals on them.

From the moment the Burgundians appeared in the capital of the Huns, Kriemhild discarded all pretense, meeting Hagen and her own brothers as sworn enemies. She is convinced that Siegfried's killer is now in her hands, and he will reveal to her where the Rhine gold is hidden. Through the fault of Kriemhild, thousands of people will die in the battles between hosts and guests. But no one’s death, even the death of her own son, does not sadden Kriemhild. She cannot calm down until Hagen and Gunther become her prisoners. The idea of Christian forgiveness is organically alien to her. This is apparently explained by the fact that the plot of the “Song of the Nibelungs” took shape in pagan times. In the finalized and recorded version, the authors of the German heroic epic, using the example of Kriemhild’s fate, show how destructive the obsession with revenge turns out to be for the avenger herself, who in the final thirty-ninth adventure turns into an ominous fury: she orders her brother’s head to be cut off. Holding in her hands the head of the one whom Hagen served, she demands that the secret of the Nibelungen treasure be revealed to her. But if in the past Hagen managed to find out Siegfried’s secret from her, now she cannot force Hagen to tell her where Siegfried’s heritage is. Realizing her moral defeat, Kriemhild takes Siegfried's sword in her hands and cuts off the head of his killer. Revenge has been achieved, but at what cost? However, Kriemhild herself does not have long to live: she is killed by old Hildebrand, who takes revenge on her for the one who was just beheaded by her, and for the fact that through her fault so many worthy knights died.

“The Song of the Nibelungs” is a story about the vicissitudes of human destinies, about the fratricidal wars that tore apart the feudal world. Etzel, the most powerful ruler of the early Middle Ages, acquired the features of an ideal ruler who paid for his nobility and gullibility, becoming a victim of those whom he revered as his closest people.

The battle of the Huns with the Burgundians in the popular consciousness becomes the root cause of the death of the Hunnic state, which was initially fragile, since it was a conglomerate of nomadic tribes. However, the historical consciousness of the people ignores objective reasons, preferring to identify world cataclysms with family feuds, modeling statehood in the image of family ties and conflicts.

The main pathos of medieval epic tales, be it “The Song of Sid” or “The Tale of Igor’s Campaign,” is a call for the consolidation of the nation, rallying around a strong central government. In the "Nibelungenlied" this idea is not expressed so clearly and definitely. The German epic consistently conveys the idea of what disastrous consequences the struggle for power leads to, what catastrophes fratricidal strife entails, how dangerous discord is within one family clan and state.

In the 70s of the XIX century. German composer Richard Wagner, based on the plot of “The Song of the Nibelungs”, which he supplemented with mythological situations, created the tetralogy “The Ring of the Nibelungs”, consisting of four operas: “Das Rheingold”, “Walkyrie”, “Siegfried” and “Twilight of the Gods”. The golden treasure, recovered from the depths of the Rhine by Siegfried, has fatal power and brings death to all the Nibelungs, especially Siegfried and Kriemhild himself, whose love is initially doomed in an ominous world where self-interest and cruelty reign.

R. Wagner also wrote operas based on the plots of the chivalric novels “Tristan and Isolde” and

The chivalric romance took a lot from the heroic epic, but at the same time the new epic genre was based on hoary antiquity.

First of all, the chivalric romance had its own author. Another thing is that sometimes many novels were written on the same plot, such as novels about the love of Tristan and Isolde. It happened that sometimes the names of the creators were lost, as happened with the charming old French story “Aucassin and Nicolet.” However, the picture of the world appears in the knightly novel in the author’s perception. The narrator in the story plays an extremely relevant role; he, as would later be the case with Byron in Don Juan or Pushkin in Eugene Onegin, will touch upon everything lightly and will sensibly discuss various topics, depending on what The knight gets into trouble. The hero of a chivalric novel is not inferior in valor to an epic hero. He has more than enough martial arts, because he can easily fight alone with a whole horde of adversaries. But now he fights not so much for the king, but for the sake of glory, which he needs to win the heart of the Beautiful Lady, in whose name he performs many feats.

The relationship between the knight and the king also changed somewhat. A noble paladin of his king, while remaining a vassal, often acquires a slightly different status: a friend and confidant of the monarch. Sometimes a knight, on the orders of the king, performs a feat, but the heroic deed is connected not with politics, but with his personal life. For example, Tristan goes to conquer Isolde. The overseas beauty is to become the wife of King Mark, who is his uncle. The distance between the vassal and the king is reduced, and the knight becomes one of those close to him. The conflict in the novel about Tristan and Isolde is based on the fact that the vassal becomes a rival of the king himself, which would be absolutely impossible in the heroic epic. The love experiences of the characters are revealed with great psychological persuasiveness, their feelings are devoid of static, the pursuit of lovers only stimulates their passion. Unlike Roland, the heroes of chivalric novels are certainly in love, love drives them, forcing them to challenge all kinds of villains and monsters to a duel, to fight with mighty giants and treacherous dwarfs. The feat takes on personal meaning, heroism becomes the primary way of self-affirmation.

However, as already mentioned, courage alone is not enough. The heroic ideal in the chivalric romance was joined by an aesthetic ideal.

It was impossible to see what kind of face Roland was through his visor, but in a chivalric romance the hero, be it Tristan or Lancelot, is always good-looking. In the same way, he is always courteous, courteous, generous, restrained in expressing feelings. Refined manners convince of the noble origin of the hero. The knight is noble, therefore, by his behavior alone he rises above the vile people.

For a knight, love is the delight of earthly life, and the one to whom he gave his heart is the living, bodily embodiment of the Madonna. These qualities formed the basis of courtliness. Cour is French for court, but “courtly” does not only mean “courtly”, it also means “exquisite”, “ideal”, “sublime”, “refined” and includes many more advantages. Courtly love was rarely mutual. Passion is inseparable from suffering. Love in knightly poetry is worship and conquest. Along with the novel, the knights created their own lyrics with strictly regulated genres. Alba sang the sorrow of separation at dawn, in pastorals a knight sought the love of a pretty shepherdess, in sirventas it was supposed to discuss political issues, and in tensons there was a philosophical debate.

Courtly poets called themselves troubadours, from the Provencal trobar, which means to seek, to find. The term “troubadour” refers to the complexity of the construction of verse, which was distinguished by its bizarre rhyme.

The chivalric romance spread throughout the territories of future Germany and France, easily overcoming the language barrier. Many novels arose about the adventures of the Knights of the Round Table at the court of King Arthur. The source was Geoffrey of Monmouth's History of the Kings of Britain (c. 1137), which became widely popular in France.

Arthur was a petty ruler of the Britons. But the Welsh author of the historical chronicle portrays him as a powerful ruler of Britain, Brittany and almost all of Western Europe. He is the supreme authority in politics, his wife Genievre is the patron of the knights in love. Lancelot, Gauvin, Yvain, Parzival and other brave knights flock to the court of King Arthur, where everyone has a place of honor at the round table. His court is the center of courtliness, valor and honor.

The most famous author of novels about the exploits of the knights of the round table was Chretien de Troyes (c. 1135 - 1191). The educated, talented trouvere was patronized by Maria Champagne, who was fond of knightly poetry. Chrétien de Troyes was prolific, five of his novels have come down to us: “Erec and Enida”, “Cliges, or the Imaginary Death”, “Yvain, or the Knight with the Lion”, “Lancelot or the Knight of the Cart”. The main conflict of his novels lies in deciding how to connect happy marriage with knightly deeds. Does the married knight Erec or Yvain have the right to sit out in the castle when the little and orphans are offended by cruel strangers? At the end of his life, for some unknown reason, he quarreled with Maria of Champagne and went to seek the protection of Philip of Alsace. “Parzival, or the Tale of the Grail” is the last novel that has not reached us, but became known thanks to a very free interpretation of Chrétien’s text, made when translated into German Wolfram von Eschenbach. The genesis of the most famous German chivalric novel goes back to a French source, but “Parzival” in German literature determined the spiritual and aesthetic search for an intellectual hero for many centuries, gave impetus to the emergence of the novel of education, without which it is impossible to imagine the literature of not only Germany, but throughout Europe.

Wolfram - the largest poet of the German Middle Ages, author of many lyrical works, the unfinished novel "Willehalm" (c. 1198-1210), is valued primarily as the creator of the monumental novel "Parzival" (c. 1200-1210), numbering 28,840 verses. But it's not a matter of scale. Wolfram von Eschenbach revolutionized the genre of the novel itself, shifting the focus from external events (adventures, unexpected meetings, fights) to inner world a hero who gradually, in the process of painful searches, disappointments and delusions, finds harmony with the world and peace of mind.

“Parzival” is a kind of family chronicle, since Wolfram von Eschenbach tells in great detail three stories - three biographies: Parzival's father Hamuret, Parzival himself and his son Lohengrin.

Gamuret is the ideal hero of a German chivalric romance. He longs to serve God alone and dreams of the only reward - the love of a beautiful lady, whose name is Herzloyda, which means yearning at heart. Herzloyd had to choose her spouse at a knight's tournament. The brave Gamuret defeats all his rivals, but he cannot live without the lists. Taking advantage of the freedom that the generous Herzloyda provided him, he went to fight and died in battle.

Parzival, the son of Gamuret and Herzloyda, at first does not know about knightly duty. Having lost her warrior husband, Herzloyda also fears for her son. The mother, along with Parzival and the servants, leaves the palace and settles in the forest. Herzloyda hopes that, living among virgin nature, Parzival will not find out what the knight's purpose is. Wolfram strives to show how a natural person, who grew up in the lap of nature, comprehends his divine destiny, which the author sees in the knightly service of goodness, justice and divine grace.

One day in the forest, Parzival saw knights galloping past him. Who are they? Mother had to explain who the knights were. Herzloyda calls knights faithful servants of the Lord God; they are on earth, fulfilling His will, serving good and light. Parzival has an irresistible desire to become a knight. In vain his mother dissuades him; he must certainly go to the court of King Arthur and take his worthy place there among the knights of the round table.

As a true hero, he defeated a whole horde of enemies of Queen Condwiramur (the name means “Created for Love”) and married her. However, Parzival has not yet realized his main purpose: to obtain the Holy Grail as a symbol of grace, connecting the earthly and heavenly worlds. This image is found in medieval legends and the Grail originally meant the vessel used at the Last Supper, into which the blood of the crucified Jesus Christ was collected. Wolfram interprets the Holy Grail somewhat differently: it is a precious stone that saturates the knight who approaches it spiritually and physically.

During his travels, the brave knight entered the mysterious and beautiful castle of Munsalves. King Anfortas was bleeding on the bed, and a squire stood next to him with a spear from which blood was dripping. Parzival was amazed by what he saw, but due to excessive modesty, he missed the opportunity to heal the king and bring to the world the joy of salvation from illness and suffering. Now he has to find the way to the mysterious castle again.

In order to further take possession of the Holy Grail and save the bleeding King Anfortas, Parzival will have to go through many tests, experience the grief and suffering of others as his own, and only then will joy illuminate the life of the valiant, illustrious knight and cleanse him of all sins committed out of ignorance.

Parzival's story ends with the triumph of justice and universal joy. His beloved wife Condviramur, whom the wandering knight had been yearning for for so long, also arrives at the castle. Happy Parzival immediately saw his wonderful sons Cardeis and Lohengrin.

The ending of the story is idyllic: the Holy Grail feeds everyone with food and quenches thirst with wine. Parzival rules his country wisely and fairly.

Lohengrin is the son of Parzival and Condwiramur. Born, like his father, after the knight left for war. Their first meeting and mutual recognition occurs when Parzival has already mastered the Holy Grail. The further history of Lohengrin is outlined by Wolfram in a dotted manner. They talk about Lohengrin's courage, about his victories in many battles. Lohengrin fell in love with the beautiful princess of Brabant, Elsa, who rejected all those who sought her hand. He arrives in Antwerp on a boat drawn by a swan. The slender, blond, handsome man Lohengrin instantly won the princess’s heart. He married her on one condition: Elsa should not ask where he came from. Obviously, Lohengrin had no right to reveal to anyone the secret of the Munsalves castle, in which the Holy Grail was kept. Lohengrin's wife for a long time complied with the condition, but as soon as she tried to find out her husband’s secret, Lohengrin disappeared without a trace, drawn by a beautiful swan.

The image of Lohengrin was reflected in the opera of the same name by R. Wagner (1848), who, being the author of the libretto himself, added new events and characters to the hero’s biography.

During the heyday of the chivalric romance and courtly poetry, the center of culture was the castle (Schloß, château), which was a fortified structure surrounded by a fortress wall and a moat. Along with living quarters, the castle had towers from which it was possible to monitor the approach of the enemy. Stained glass was installed in the windows, and the floor was covered with carpets. The rooms were heated by a fireplace. The castle had a state hall where ceremonies, meetings, feasts, poetry tournaments and litigation took place. There was a prison in the castle's dungeon.

The feudal castle with its walls, towers and gates traced its origins to Roman military fortifications and a German manor. The architecture of the castle has undergone changes over time, the defensive nature of the structure was lost, and the castle turned into a dwelling - houses, palaces.

From the middle of the fifteenth century. The house of Jacques Coeur in Bourges has been preserved, representing an example of the transition from castle architecture to palace architecture. The richest merchant and financier began to build his luxurious home on the crest of success. Stained glass was inserted into the windows, the walls inside and out were covered with lush decorations, the ceilings were painted, and the hall was decorated with works of painters and sculptors. The house had all kinds of amenities, including a bathhouse. There was a huge fireplace topped with a tower (a castle within a castle!), decorated with a frieze depicting a picaresque procession: knights and hunters riding monkeys. Apparently, the rich man did not miss the opportunity to laugh at the poor knights who were leaving the historical arena.

The Louvre was a transitional structure  and Tower, built in the 14th century.

and Tower, built in the 14th century.

If the castle was the center social life, then the center of spiritual life was the cathedral. Christian churches were built at the end of the first millennium; their dominant style was Romanesque. The temple had a basilica as its starting point, that is, the building was rectangular in shape, and was divided into three, five, sometimes more naves by rows of columns. The central nave stood out for its size. The architects of Christian churches borrowed the form of the basilica from the Romans, who used it in the construction of buildings for legal proceedings or trade.

Accordingly, the style that arose on the basis of the ancient Roman tradition was called Romanesque and was characterized by massiveness and simplicity of forms, vaulted and arched structures, and laconic sculptural decorations. Not many churches, let alone Romanesque castles, have survived. Examples include the cathedral in Bamberg, built in 1009-1012, and the cathedral in Worms.  , built in 1171-1234. However, certain features of Romanesque architecture can also be found in later buildings designed in the Gothic style.

, built in 1171-1234. However, certain features of Romanesque architecture can also be found in later buildings designed in the Gothic style.

Gothic as an architectural style originally originated in northwestern France and then spread throughout western Europe. The Gothic style is characterized by asymmetrical building volumes of varying sizes, which have a clear vertical orientation. Gothic style is characterized by pointed arches and vaults, an abundance of stone carvings, and stained glass windows. In a Gothic cathedral, the thrust of the pointed vault of the main nave is transmitted to the external supporting pillars (buttresses) using thrust arches (flying buttresses). The Gothic style is applicable exclusively to church architecture; only certain Gothic details and techniques could be used in the construction of palaces.

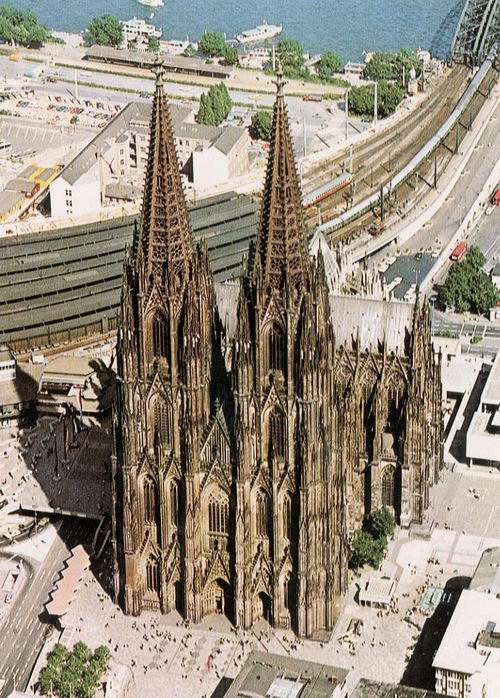

The earliest Gothic buildings include the chapel in Saint-Denis, built by Abbot Sugerius between 1140 and 1143, and then the cathedrals of Chartres, Reims and Amiens, dating back to the beginning of the 13th century. The construction of cathedrals was a long process. In this regard, a kind of record was set in Cologne, where they began to build St. Peter's Cathedral in 1248. By 1320, an altar, five naves and a bell tower almost 160 m high were built. Construction slowed down, and only by 1400 the southern tower and southern side naves. However, at the beginning of the 16th century, in connection with the Reformation started by Martin Luther, the Catholic cathedral was stopped being built altogether. Only in mid-19th V. work resumed, and in 1880 the bulk of the cathedral in its completed form appeared before the eyes of the residents of Cologne. But it is worth paying attention to the fact that the construction of the cathedral lasted more than seven centuries, that architectural styles changed, but the cathedral remained faithful to the Gothic style and, based on drawings and plans, was completed in the form in which it was originally conceived. (Cm.  ,

,  ,

,  )

)

The term Gothic itself began to be used in the 16th-17th centuries. to denote a pre-Renaissance non-Italian style. Time has made adjustments to terminology and discovered the attractiveness of the Gothic style. Sometimes the architecture of the cathedral became eclectic, which is associated with a change in styles, as happened during the construction of Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris  , founded in 1163 and completed in the 14th century. This is how Victor Hugo describes the appearance of the cathedral in the famous novel “Notre Dame Cathedral” (1831): “If the reader and I had the leisure to trace one by one all those traces of destruction that were imprinted on this ancient temple, we would notice that The share of time here is insignificant that the greatest harm was caused by people, and mainly by people of art. I am forced to mention “people of art”, because within two last centuries Among them were individuals who appropriated the title of architects.

, founded in 1163 and completed in the 14th century. This is how Victor Hugo describes the appearance of the cathedral in the famous novel “Notre Dame Cathedral” (1831): “If the reader and I had the leisure to trace one by one all those traces of destruction that were imprinted on this ancient temple, we would notice that The share of time here is insignificant that the greatest harm was caused by people, and mainly by people of art. I am forced to mention “people of art”, because within two last centuries Among them were individuals who appropriated the title of architects.

First of all - to limit ourselves to just a few of the most significant examples - it should be pointed out that there is hardly a page in the history of architecture more beautiful than that of the facade of this cathedral, where three lancet portals appear successively and in totality; above them is a crenellated cornice, as if embroidered with twenty-eight royal niches, a huge central rose window with two other windows located on the sides, like a priest standing between a deacon and a subdeacon; a tall, graceful gallery arcade with trefoil-shaped mouldings, supporting a heavy platform on its slender columns, and finally two gloomy, massive towers with slate canopies. All these harmonious parts of the magnificent whole, erected one above the other in five gigantic tiers, serenely in infinite variety unfold before the eyes their countless sculpted, carved and chased details, powerfully and inseparably merging with the calm grandeur of the whole. It's like a huge stone symphony; a colossal creation of both man and people; unified and complex, like the Iliad and Romancero, to which it is related; a wonderful result of the combination of all the forces of an entire era, where from every stone the imagination of the worker, taking hundreds of forms, splashes out, guided by the genius of the artist; in a word, this creation of human hands is powerful and abundant, like the creation of God, from which it seems to have borrowed its dual character: diversified and eternal.

What we say here about the façade should also apply to the cathedral as a whole; and what we're talking about cathedral Paris, one should say about all the Christian churches of the Middle Ages."

However, the cathedral was perceived by parishioners primarily not as a work of art, but rather as an encyclopedia of spiritual life.

The cathedral was called to perpetuate and glorify Jesus Christ, the Mother of God, and the apostles. The life of the Savior, Madonna or his disciples became the main content of the cathedral. Through individual events, builders and sculptors were able to convey the entire history of the Christian church. Gothic cathedrals were built with the goal of embodying transcendental existence on earth.

The cathedral performed the most important function of a reliquary. Thus, in the Cologne Cathedral the relics of the eastern kings-magi are kept, who came with gifts to be the first to worship the baby Jesus. The Holy Grail is kept in the Valencia Cathedral. In the Church of St. Nicholas in Demre (Myra of Lycia) the relics of Nicholas the Wonderworker, who served as a bishop in the same church, are kept. In the future, this tradition of burying clergy in the temple will be established everywhere. In Canterbury Cathedral, where Bishop Thomas was killed, his relics were preserved as a shrine.

Each cathedral, possessing its own relics, attracted local parishioners and pilgrims who wanted to venerate the shrines.

In addition, church utensils, which were works of jewelry, were kept in the cathedral.

In Catholic churches there is no painting, but there are stained glass windows with religious scenes, which, as a rule, recreate the most important events of the Christian denomination.

In cathedrals, the walls were decorated with paintings by the greatest artists, which could be dedicated to the lives of local saints. For example, the Cologne artist Stefan Lochner painted paintings for the cathedral based on the life of St. Ursula, a local native. Caravaggio painted the grandiose painting “The Beheading of John the Baptist” for the Cathedral of St. John the Baptist in the city of La Valeta in Malta. There are many examples that can be given, but the main thing to keep in mind is that most of the paintings on religious subjects that are on display in museums today were intended for churches. "Sistine Madonna"  in the Dresden Gallery it is called “Sistine” because it was intended for the Sistine Chapel.

in the Dresden Gallery it is called “Sistine” because it was intended for the Sistine Chapel.

The Gothic cathedral amazes with its stone sculpture. The walls of the cathedral have no free space; it is completely covered with stone carvings - decorative and narrative. Inside the cathedral there are always sculptures of saints, sometimes dating back to various medieval periods. In the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris, the wall is decorated with the relief “Job and His Friends” (13th century), which is striking in its psychologism: the friends do not sympathize with the sufferer, but rather gloat.

The cross chapel of Cologne Cathedral is decorated with a crucifix commissioned by Bishop Gero (d. 976), which is considered the oldest of the monumental crucifixes in Western Europe. Christ presented an ordinary person who accepted martyrdom. There is more suffering in his bent figure than greatness. According to legend, the crack that split the head of the wooden crucifix closed again after Bishop Gero applied prosvira to it. Since then, the crucifixion has been recognized as miraculous.

If you consider all the various works in the Gothic cathedral visual arts, then it is not difficult to discover that the plot of almost everyone becomes a miracle, but only a true believer is destined to experience a miracle. The greatest poet of medieval France, Francois Villon, aphoristically said this in the ballad of the “Poetic Competition in Blois”: “I doubt the obvious, I believe in a miracle.” In essence, the entire Middle Ages lived in anticipation of miracles.

Such is the “Miracle of Theophilus,” a story that took place in a church in Cilicia around 538 and is depicted in the north portal of Notre Dame Cathedral. The church steward, angry that the cardinal did not promote him, sold his soul to the devil. However, he came to his senses in time and turned to Madonna with prayer. The Mother of God saved him from the torments of hell, taking away the sinner’s soul from the evil demon. This plot, which also served as the basis for Ruytbeuf’s dramatic work “The Miracle of Theophilus,” is very indicative of the medieval consciousness: if you have sinned, hasten to repent and you will be saved.

With the invention of artillery, knighthood gradually lost its social role, but the burghers - the townspeople, united in craft workshops and merchant guilds - grew stronger. By the beginning of the 12th century. Burgher literature was formed, in opposition to the chivalric romance and courtly lyricism. The townspeople had their own genres, and turning to already formed genres, the townspeople parodied them. Urban culture was to a certain extent based on carnival traditions: the townspeople were largely characterized by a sense of freedom and independence, which arose during the festivities and was accompanied by dressing up, games and tomfoolery. Let us recall once again V. Hugo’s novel “Notre Dame de Paris,” where they choose not a beautiful queen, but a king of freaks, whose title easily goes to the half-man, half-monster Quasimodo.

Famous domestic scientist M.M. Bakhtin discovered entire layers of medieval carnival culture, which he valued extremely highly: “Celebrations of the carnival type, as we have already said, occupied a very large place in the life of medieval people even over time: large cities of the Middle Ages lived a carnival life for a total of up to three months a year . The influence of the carnival worldview on people's vision and thinking was irresistible: it forced them, as it were, to renounce their official position (monk, cleric, scientist) and perceive the world in its carnival-ludicrous aspect. Not only schoolchildren and minor clergy, but also high-ranking clergy and learned theologians allowed themselves cheerful recreations, that is, a break from reverent seriousness, and “monastic jokes” (“Ioca monacorum”), as one of the most popular works of the Middle Ages was called. In their cells they created parodies or semi-parodies of learned treatises and other humorous works in Latin.

The humorous literature of the Middle Ages developed over a whole millennium and even more, since its beginnings date back to Christian antiquity. Over such a long period of its existence, this literature, of course, underwent quite significant changes (literature in Latin changed the least). Various genre forms and stylistic variations were developed. But despite all the historical and genre differences, this literature remains, to a greater or lesser extent, an expression of the folk-carnival worldview and uses the language of carnival forms and symbols.”

However, it seems that the scale of carnival liberties should not be exaggerated; medieval man was a deeply religious person, he sacredly observed church calendar, in which the martyrdom and asceticism of the holy apostles and their followers occupied a prominent place.

The combination of tragic and comic occurred in dramatic genres. In the temple, the service was to a certain extent theatrical in nature: the decoration of the temple was stage decoration, the exchange of remarks between the two semi-choirs was dialogue, biblical texts were accompanied by music. Sometimes improvisation was allowed during the service. Liberties were introduced into the text, mise-en-scène was allowed. This kind of improvisational drama is called liturgical. However, soon the performance was brought to the porch, and not only clergy, but also ordinary townspeople began to take part in the staging of gospel episodes. This is how semi-liturgical drama appeared.

The grandiose performance that took place in the city square was a mystery (Latin mysterium - sacrament). It could be an action about the fall of Adam and Eve or a depiction of the way of the cross of Jesus Christ. Comic episodes began to penetrate serious dramatic performances. A farce appeared (French farce - filling), which depicted unfaithful wives, imaginary blind men begging for alms, scoundrel lawyers, stingy old men and helipads in love. The writers of farces laughed at them kindly, amusing the spectators who had gathered to watch the mysteries.

A drama with a happy ending was a miracle (French miracle - miracle). In the miracles, heavenly powers intervened in the fate of the sinner and saved him. This is the already mentioned miracle “The Miracle of Theophilus” by Rutbeuf (mid-13th century). Nicholas of Myra often acted in the miracles, saving drowning sailors, helping homeless women find worthy suitors, curing the sick, and even exposing thieves.

Short humorous stories, poetic or prose, which in France were called town halls - the buildings where city administration was concentrated, were extremely popular in the urban environment. They retain the stylistic features of Gothic, but look much more mundane, and the stone carvings on the facade of the town hall are much more modest than in the cathedral. Examples include those erected at the beginning of the 15th century. Gothic-style red-brick town halls in Rostock, Wernigerode, Goslar, Lübeck and other German cities. Other public institutions are being built. For example, baths that appeared in Europe after the Crusades under the influence of the culture of the East.

Knights returning from the Crusades or simply after battles needed to be treated. At the end of the Middle Ages, the first special medical institutions were built. A typical example of this kind of structure is the Hospital of the Holy Spirit in Lübeck (1210-1230). The vaulted halls resembled a temple, but along with the main entrance, where the suffering were received, there was a huge closed room, divided into tiny closets, where wounds were treated and where homeless warriors lived out their days. In the capital of Malta, in the city of Lavvallet, today you can see the Obrege de Castille, built at the end of the Middle Ages - an infirmary for wounded knights, which also served as a refuge for the elderly and sick. They were looked after by members of the Order of Malta Hospitallers, famous for their healers.

It is impossible not to mention that universities appeared everywhere in Europe, starting from the 12th century.

All this together prepared the way for the revival of ancient humanistic traditions.

The transition from one era to another was smooth, gradual, beginning in Italy at the end of the 13th century. early XIV centuries

The great poet Dante and the brilliant painter Giotto connected the Middle Ages with the Renaissance with their creativity. While preserving the features of the medieval vision of the world, they at the same time managed to look into the future of humanity.

Giotto di Bondone (1267 - 1336) born in the town of Vespignano near Florence. Little is known about his life. He knew well and accurately depicted village life. Some biographers have therefore suggested that he came from a peasant family. A hypothesis arose that he was a follower of Francis of Assisi, who, having renounced wealth, preached poverty and argued that God, dissolved in all nature, can be comprehended by a special state of mind that meditation causes. The occasion was Giotto's early work - 28 frescoes from the life of the founder of the Franciscan order, in a church in Assisi. The frescoes consistently recreate the life of the saint. Here Francis renounces his father, then gives his cloak to someone in need, drives out demons, and draws water from a rock. One of the most striking and poetic frescoes “St. Francis preaches to the birds,” where the artist managed to convey the amazing unity of man and nature, which, in fact, brings him closer to the Renaissance.

Giotto himself was not an apostle of poverty; he was characterized by common sense rather than religious ecstasy. It should be noted that the artist who received orders to paint temples was never an opponent of the pope and in this way was strikingly different from his contemporary and fellow countryman Dante.

Giotto visited Rome, then Padua, Rimini, and decorated churches with mosaics and frescoes. He bought himself a house in Florence near the church of Santa Maria Novella, was a wealthy man, conducting his business very successfully.

Giotto's most significant work is the frescoes in the Church of Maria dal Arena in Padua. 32 scenes depict the earthly life of Mary and Jesus Christ. He depicted the Mother of God not as the queen of heaven, as was customary in Gothic, but as a mother sharing the suffering and torment of her son. In the interpretation of the last days of the Savior, a special sincerity is felt, His humility in the frescoes “Washing of the Feet” and “The Last Supper”. Depicting the mourning of Christ, Giotto, with smoothly repeating rounded lines, recreates the universal focus on a global event. At the same time, the Son of God remains a man here too. (Cm.  ,

, ![]() ,

,  )

)

Giotto received an invitation from the Neapolitan king Robert of Anjou, who patronized artists and poets, to paint the court chapel, which should have contained portraits of noble persons painted by Giotto. Alas, they have not survived, like many of his other works.

Giotto and Dante knew each other. Perhaps the creation of the Last Judgment fresco was influenced by Dante's poem, and the only more or less reliable portrait of Dante  belongs to the brush of Giotto.

belongs to the brush of Giotto.

Dante Alighieri (1265 - 1321) born in Florence, took an active part in public life, was elected one of the priors - the governors of the city. However, when Dante's political opponents came to power, he was forced to go into exile. Although famous poet He was received with honors in many cities of Italy; he had a hard time being separated from Florence. The most important event The poet's spiritual life was a meeting with Beatrice, who became for him the earthly embodiment of heavenly love. The name Beatrice means bestower of bliss. Dante's poetic work became a glorification of the ideal; he created an image that embodies faith, wisdom, beauty, justice, compassion - in a word, all human virtues.

He first spoke about his love for Beatrice in the book “ New life"(1292), which became the world's first autobiography of a poet. He talks about meetings with Beatrice, of which there were only three. He experienced bliss when he beheld her lovely appearance. He experienced terrible grief when he learned that Beatrice had died. In "New Life" poetry is combined with prose. In sonnets and canzones he captured her image, and in prose explanations he talked about what was the reason for creating the poem and what thought he wanted to express in it.

Dante worked on The Divine Comedy in exile for about 20 years. The poet called his work “Comedy”. This did not mean belonging to the dramatic genre; in the time of Dante, a comedy was a work that begins tragically but ends happily. Descendants called Dante's creation "Divina commedia", thereby expressing their admiration. The poem consists of three parts: “Hell”, “Purgatory”, “Paradise”, corresponding to the three states of the human soul in the afterlife. Each part consists of 33 songs, in addition to this there is an introductory song that begins like this:

Having completed half my earthly life,

I found myself in a dark forest,

Having lost the right path in the darkness of the valley.

What he was like, oh, as I say,

That wild forest, dense and threatening,

Whose old horror I carry in my memory!

He is so bitter that death is almost sweeter.

But having found goodness in it forever,

I’ll tell you about everything I saw in this place.

(Translation by M. Lozinsky).

The poem is written in terzas, that is, stanzas, each of which consists of three lines, and first the first and third lines rhyme, and then the second line in the next stanza rhymes with the first and third. Note that in Dante’s works the number three has a special meaning associated with the trinity of the deity.

According to medieval ideas, the average lifespan is 35 years. The dark forest is a symbolic image illustrating human misconceptions. Next, three allegorical beasts will appear, personifying the vices, weaknesses and sins of people. To guide the poet on the true path, the merciful Beatrice, who lives in paradise, sent Virgil to him so that he would lead Dante through the circles of hell and show how sinners are punished. Through the eyes of the astonished Dante, the reader sees gluttons and voluptuaries, heretics and blasphemers, deceivers, flatterers, bribe-takers and traitors. Each one is destined for punishment according to his sins, which Dante considers fair, but this does not prevent him from having compassion for the inhabitants of hell. So, in the fifth song he depicts real people Francesco da Rimini and Paolo. They fell in love, although Francesco was the wife of Paolo's brother. The poet's imagination makes them spin in a terrifying hellish whirlwind. Dante punishes them, but he also falls unconscious upon hearing the confession of his heroine. Likewise, in many other episodes, Dante does not deviate from medieval religious dogmas, but humanistically sympathizes with suffering.

The most terrible crime in the poet's mind is betrayal. The most painful tortures are in store for Judas, Brutus and Cassius. Dante, who has experienced treason and betrayal, is merciless towards them.

At the end of the poem, Dante meets with Beatrice, who introduces him to Divine Providence and eternity.

In art history, the term “ducento” is adopted - the 12th century, called the proto-Renaissance, that is, the historical stage immediately followed by the Renaissance.

Alekseev M.P., Zhirmunsky V.M., Mokulsky S.S., Smirnov A.A. History of Western European literature. Middle Ages and Renaissance. - M., 2000.

Bakhtin M.M. The work of Francois Rabelais and the folk culture of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. - M, 1965.

Gurevich A.Ya. Problems of medieval literature. - M., 1981.

Danilova I.E. Art of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. - M., 1984.

Huizinga I. Autumn of the Middle Ages. - M., 1988.