Otherwise it may be questioned and deleted.

You can edit this article by adding links to .

This mark is set February 21, 2017.

Dependent Peasants - common name one of the two main socio-economic classes of medieval society during the era of classical feudalism. A group of personally dependent peasants was ruled by warrior-landowners, the so-called feudal lords, who protected the peasants from attacks by other feudal lords both through active military action and other methods, for example, by providing them with protection within the walls of their castle, trading areas for fairs, warehouses, and so on. The dependent peasantry replaced the slavery of antiquity. The main difference between a personally dependent peasant (serf) and a slave was the fact that the former had the right to life, that is, for the murder of a serf, the feudal lord (or landowner) should theoretically be held criminally liable by law, although in practice serfs, especially in Russian Empire, were actually equal to slaves. The position of the dependent peasantry varied across countries and regions of Europe, and also evolved depending on the time period. With the spread of capitalism in the 17th-19th centuries, dependent peasants and feudal lords were replaced by hired workers and capitalists. Unlike slaves, peasants could have private property and engage in commerce. The peasant himself could not be sold, the object of sale and purchase was the land to which he was attached.

Story

In the territories of the former Roman Empire and Byzantium, the dependent peasantry developed from an intermediate class - the so-called coloni of late antiquity, who, unlike slaves, were semi-free tenant farm laborers who populated the outskirts of the empire (Gaul, Spain). In medieval Spain and Latin America they became known as peons. In the Germanic and Slavic lands, which did not know long-term slavery, the dependence of the peasants arose as a result of the property and resource stratification of society, as well as under the influence of neighboring (Roman and Eastern) regions. Not all peasants of medieval Europe were dependent on feudal lords. This is how the military peasants Akrites lived in Byzantine Anatolia. At the same time, slavery in medieval Europe was also common in many cities, although on a smaller scale compared to classical antiquity. In general, in the X-XII centuries. In Western Europe, two main classes of medieval society emerged: dependent peasants and warrior-landowners. Each group had its own way of life, its own worldview and its own position in society.

Differences between countries

In some northern countries with the farm type of farming (Norway, Iceland), dependent peasants did not develop as a class at all. In each country and even region where feudalism became stronger, dependent peasants were called differently. The situation also varied greatly. Thus, in England, settled by the Germans in the 6th century, serfdom (in the Russian sense of the word) was extremely weak and personal forms of dependence of the peasants began to disappear already in the 12th-13th centuries, being completely eliminated by the 15th century. In France, which knew classical Roman slavery, various shapes Serfdom persisted much longer - until the end of the 18th century. In Russian historiography, dependent peasants became known as

The lands of the feudal lords were divided among the peasants. Not just most of medieval feudal estate - seigneury consisted of the direct economic use of the landowner (lord's land), and most of it was cultivated by peasants as independent owners. Significant features distinguished the legal status of the peasant allotment. The peasants hereditarily owned plots of the master's land, used it as independent owners under the condition of paying quitrents and performing corvée work, and were subject to the court and government of the master.

Peasants could either be personally free farmers or dependent in varying degrees and forms on landowners. The peasants were divided into three main groups (categories) according to what duties they bore in favor of the feudal lords: personally dependent peasants, land dependent peasants and free peasants - owners (allodists).

Medieval jurists distinguished three types of subordination of the peasant to the lord. These were personal, land and judicial dependence. The legal signs of personal dependence were the following. A personally dependent peasant did not have the right to inherit his allotment to anyone without paying his lord a special contribution, consisting of either part of the property - the best head of cattle, the wedding decoration and dress of his wife, or, in later times, from a certain amounts of money. He paid a “universal” tax. Marriages between persons dependent on different lords were prohibited. A special fee was required for permission for such a marriage. All other duties were not precisely defined and were collected at the will of the lord, when, where and as much as he pleased.

Land dependence stemmed from the fact that the peasant plot belonged to the lord. The land of the peasant allotment legally constituted part of the estate, due to which the peasant had to bear various duties - in the form of corvee or quitrents, usually in proportion to the size of the allotment and in accordance with customary law.

The judicial dependence of the peasants stemmed from the immunity rights of the lord. The charter of immunity gave the feudal lord the right to conduct justice on the territory specified in it, which was larger than the estate. This dependence was expressed in the fact that the population had to be tried in the court of the immuneist. All judicial fines, as well as those duties that previously went to the king or his representatives for the exercise of judicial and administrative functions, no longer went in favor of the king, but in favor of the lord. As a representative of administrative power, the lord kept order in public places, for example, in markets, big roads and, in accordance with this, collected market, road, ferry, bridge and other duties and had the right to income from the so-called banalities - feudal monopolies.

The most common were three types of banalities - furnace, mill and grape press banalities. Persons who were judicially dependent on the lord were obliged to bake bread only in an oven specifically designated by the lord or belonging to him, were obliged to press wine only under the lord’s press and grind grain only at his mill.

Associated with the judicial-administrative rights of the lord was the right of the lord to demand corvee for repairing roads, bridges, etc. The feudal lords transferred the corvee for repairing roads to their fields and turned public service into ordinary lord's corvee.

Land tenure of personally dependent peasants

Personally dependent peasants - serfs in France, villans in England and grundgolds in Germany were in personal, land and judicial dependence on their master. They only had the right to own and use a plot of land, the owner of which was recognized as the owner of this peasant. For the ownership and use of an allotment, personally dependent peasants had to pay the lord an annual rent in kind in the form of domestic animals, crops, grain bread, food, or cash, the amount of which was established by the lord.

Corvée was also established by the master at his own discretion. Corvee is compulsory free labor in the feudal economy, since workers were needed to cultivate the land of the feudal lord - plowing, sowing, grazing, reaping, threshing. This was the cultivation of the master's land by peasants under the supervision of a clerk. Corvée work included the duty of peasants to supply carts and transport the master's goods from one estate to another or to the city for sale. The most characteristic sign of personal dependence was the uncertainty of corvee duties and the possibility of their arbitrary increase by the feudal lord.

Personally dependent peasants were deprived of the right to leave the land on which they worked without the consent of the master. In the event of the escape of a personally dependent peasant, the feudal lord had the right to pursue and bring him back. This right was limited by limitation, which in many cases was determined to be one year and one day. Personally dependent peasants are sometimes called serfs, which is inaccurate. Unlike personally dependent peasants, serfs were subject to an indefinite search by the state authorities and return to their previous owners. Over time, personally dependent peasants acquired the right to leave the feudal lord, but, having warned him about this in advance, they left their plot and movable property in his favor.

Personally dependent peasants could be sold or given away along with their family, but they could not be killed or mutilated. They were subject to the judgment of their master, who had the right to corporally punish them. They were deprived of the opportunity to seek protection against their master in the royal court.

A personally dependent peasant could not make any transactions with the land plot without the consent of the master. After the death of a personally dependent peasant, all his property could be taken by the master, that is, there was the so-called right of a dead hand. The peasant's hand was dead to transfer the inheritance to his son, but the feudal lord's hand turned out to be alive. The heirs of the deceased could get rid of this situation only through ransom, transferring to their master their best property, usually the best head of cattle. To marry, personally dependent peasants required the master's permission, so they paid a wedding fee to the lord.

The personally dependent peasant was the owner of movable things - draft animals, tools, feed for livestock, seeds for sowing, products of labor, and could alienate them, even if sometimes this required the permission of his master. Such permission was only a restriction of the right of disposal of a personally dependent peasant with his movable property, but not a complete denial of this right to him. The “dead hand right” was also a limitation on property rights.

Thus, personally dependent peasants were free persons, subjects of law, but their legal capacity and capacity were limited. This was due to the power of the master over the personality of the farmer.

It began to take shape in European countries in the mid-16th century. It was then that a special class of population was identified - peasants who lived on the territory of a landowner or feudal lord and were dependent on him in whole or in part. All peasants, without exception, were subject to conscription. The forced duties of this class were numerous: from daily labor on the feudal lord's estate to military service. The severity of the labor burden depended on many factors, including the age of the peasant, his abilities and skills. Often, feudal lords, using their power, could impose additional burdens on those for whom they had personal hostility. It was the forced duties of dependent peasants that became the main topic presented in this article.

Dependent peasants: who are they?

Let us consider the forms of peasant dependence on the landowner or feudal lord: complete and incomplete. Peasants who were completely dependent on the owner were usually called personally dependent. Their position in society was one of the most deplorable. They not only did not have the right of ownership of any household items, including clothing, but also the right to free expression of will and even to their own lives. This form of peasant dependence was characteristic of states in which slavery flourished. The forced duties of dependent peasants from this class could not be challenged even if the owner treated them inappropriately. The feudal lord, in turn, had the right to sentence the peasant to and even deprive him of his life for any offense.

The incomplete dependence of the peasants consisted mainly in their economic subordination to the feudal lord. One of the forced duties of dependent peasants is to work in the fields or in the owner’s workshops. While serving his estate or estate, they at the same time had personal rights: they could move freely, acquire or sell their own property. In addition, if cruelty or unfair treatment was shown to a peasant, the feudal lord could be subject to legal proceedings. The forced labor of a dependent peasant in the case of his incomplete dependence was reduced to working off a debt or rent for the use of a land plot given to him by the feudal lord. Due to the fact that many peasants did not have the opportunity to acquire ownership of land or equipment for cultivating it, feudal lords often took advantage of this, and the “debts” were returned to them within several decades.

Signs of forced labor in a feudal economy

Like any economic or social phenomenon, the forced obligations of dependent peasants can be determined using several characteristic features, which include the following:

- The dependent peasant has the use of land, which is the property of the feudal lord.

- In addition to working on his own land plots, the peasant also cultivated that plot of land that was listed as “lordly”, and all the products from it went exclusively to the feudal lord.

- To cultivate land plots (peasant and lordly), agricultural implements were used, including horses belonging to the peasant.

- For dishonest performance of forced labor, a peasant could be punished in the form of an increase in the amount of tax in kind (quitrent) or an additional period of unpaid work for the feudal lord (corvée).

Otherwise, the forms of forced peasant labor in feudal production are somewhat different. Let's take a closer look at each of them.

Peculiarities of running a corvée economy

As mentioned above, in medieval Europe there were several types of work for which forced people did not receive payment. One of the forced duties of dependent peasants - corvee - was widespread throughout almost the entire territory of Western and of Eastern Europe, including Rus'. The essence of this type of labor service was the free labor of the dependent population on the fields of the feudal lord using their own equipment. At the same time, the peasant cultivated his plot of land, growing and producing food for his own consumption. The main disadvantage of the corvee system was the constant need for supervision on the part of the feudal lord, because often forced work was carried out by peasants on a “somehow” principle.

In the states of the Middle Ages, corvée (forced labor of dependent peasants) existed from approximately the 8th-9th to the 18th century. This form of unpaid labor became most widespread on the territory of the state of Rus' and existed there almost until the end of the 19th century under the name “sharecropping.”

Features of quitrent farming

Another of the forced duties of dependent peasants in medieval Europe - quitrent - existed at about the same time as corvée. The essence of this phenomenon was that almost all the land of the feudal lord was given for the use of the peasant who cultivated it on our own using your own equipment.

The harvest received from the plots was divided into two parts, one of which went as payment to the feudal lord, and the other was used by the peasant at his own discretion. In connection with the spread and development of crafts, natural (food) rent was combined with monetary rent, and in some estates it was completely replaced by it. Such forced duties of dependent peasants, such as quitrents in kind and cash, served as an impetus for an even greater division of labor and, as a consequence, the development of commodity-money relations.

Working rent

Labor rent as a form of forced labor was one of the easiest. In her case, the dependent peasant received from the feudal lord a land plot, animals for breeding, agricultural tools and other equipment. As payment for the use of these benefits, he had to work in the landowner's production for a certain period of time. By the way, such a system of forced labor was most widespread in the countries of the East, where there was practically no personal dependence of the peasants. Rent was often paid in products produced on the dependent peasant's farm, household items, jewelry, textiles, or money.

The way of life of a person in the Middle Ages largely depended on his place of residence, but the people of that time were also quite mobile, being in constant movement. Initially, these were echoes of the migration of peoples. Then other reasons pushed people on the road. Peasants moved along the roads of Europe in groups or individually, looking for a better life. Only over time, when peasants began to acquire some property, and feudal lords acquired lands, cities began to grow and villages appeared (approximately the 14th century).

Peasants' houses

Peasant houses were built of wood, sometimes preference was given to stone. Roofs were made of reeds or straw. There was little furniture, mainly tables and chests for clothes. They slept on beds or benches. The bed was a mattress stuffed with straw or a hayloft.

Houses were heated by fireplaces or hearths. Stoves appeared only at the beginning of the 14th century; they were borrowed from the Slavs and northern peoples. The housing was illuminated with oil lamps and tallow candles. Expensive wax candles were available only to rich people.

Peasant food

Most Europeans ate rather modestly. We ate twice: in the evening and in the morning. Everyday food was:

1. legumes;

3. cabbage;

5. rye bread;

6. grain soup with onions or garlic.

They consumed little meat, especially considering that there were 166 days of fasting a year, and it was forbidden to eat meat dishes. The diet included significantly more fish. The only sweet thing is honey. Sugar came to Europe from the East in the 13th century; it was very expensive. In Europe they drank a lot: in the north - beer, in the south - wine. Instead of tea, herbs were brewed.

European dishes (mugs, bowls, etc.) were very simple, made of tin or clay. We ate with spoons, there were no forks. They ate with their hands and cut the meat with a knife. The peasants ate food with the whole family from one bowl.

Cloth

The peasant usually wore linen trousers to the knees or even to the ankles, as well as a linen shirt. The outer clothing was a cloak, fastened with a clasp (fibula) on the shoulders. In winter they wore:

1. a warm cape made of thick fur fabric;

2. roughly combed sheep's coat.

The poor were content with dark-colored clothing made of coarse linen. The shoes were pointed leather boots without hard soles.

Feudal lords and peasants

The feudal lord needed power over the peasants in order to force them to fulfill their duties. In the Middle Ages, serfs were not free people; they depended on the feudal lord, who could exchange, buy, sell the serf. If a peasant tried to run away, he was searched for and returned to the estate, where reprisals awaited him.

For refusing to work, for not turning in the quitrent on time, the peasant was summoned to the feudal court of the feudal lord. The inexorable master personally accused, judged, and then carried out the sentence. The peasant could be beaten with whips or sticks, thrown into prison or chained.

Serfs were constantly subject to the authority of the feudal lord. The feudal lord could demand a ransom upon marriage, and could marry and marry off serfs himself.

The life of peasants in the Middle Ages was harsh, full of hardships and trials. Heavy taxes, devastating wars and crop failures often deprived the peasant of the most necessary things and forced him to think only about survival. Just 400 years ago in richest country Europe - France - travelers came across villages whose inhabitants were dressed in dirty rags, lived in half-dugouts, holes dug in the ground, and were so wild that in response to questions they could not utter a single articulate word. It is not surprising that in the Middle Ages the view of the peasant as half-animal, half-devil was widespread; the words “villan”, “villania”, denoting rural residents, meant at the same time “rudeness, ignorance, bestiality.”

There is no need to think that all peasants in medieval Europe were like devils or ragamuffins. No, many peasants had gold coins and elegant clothes hidden in their chests, which they wore on holidays; the peasants knew how to have fun at village weddings, when beer and wine flowed like a river and everyone was eaten up in a whole series of half-starved days. The peasants were shrewd and cunning, they clearly saw the advantages and disadvantages of those people whom they had to encounter in their simple lives: a knight, a merchant, a priest, a judge. If the feudal lords looked at the peasants as devils crawling out of hellish holes, then the peasants paid their lords in the same coin: a knight rushing through the sown fields with a pack of hunting dogs, shedding someone else’s blood and living off someone else’s labor, seemed to them not a person, but a demon.

It is generally accepted that it was the feudal lord who was the main enemy of the medieval peasant. The relationship between them was indeed complicated. The villagers more than once rose up to fight against their masters. They killed the lords, robbed and set fire to their castles, captured fields, forests and meadows. The largest of these uprisings were the Jacquerie (1358) in France, and the uprisings led by Wat Tyler (1381) and the Ket brothers (1549) in England. One of the most important events in the history of Germany was the Peasants' War of 1525.

Such formidable outbursts of peasant discontent were rare. They happened most often when life in the villages became truly unbearable due to the atrocities of soldiers, royal officials or the attack of feudal lords on the rights of peasants. Usually the villagers knew how to get along with their masters; Both of them lived according to ancient, ancient customs, which provided for almost all possible disputes and disagreements.

Peasants were divided into three large groups: free, land dependent and personally dependent. There were relatively few free peasants; they did not recognize the authority of any lord over themselves, considering themselves free subjects of the king. They paid taxes only to the king and wanted to be tried only by the royal court. Free peasants often sat on former "nobody's" lands; these could be cleared forest glades, drained swamps, or lands reclaimed from the Moors (in Spain).

A land-dependent peasant was also considered free by law, but he sat on land belonging to the feudal lord. The taxes that he paid to the lord were considered as payment not “per person”, but “from the land” that he uses. In most cases, such a peasant could leave his piece of land and leave the lord - most often no one would hold him back, but he basically had nowhere to go.

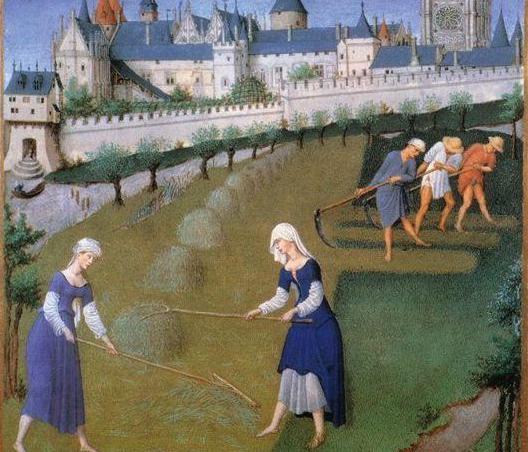

"Peasants at work." French miniature of the 16th century.

Finally, the personally dependent peasant could not leave his master when he wanted to. He belonged body and soul to his lord, was his serf, that is, a person attached to the lord by a lifelong and indissoluble bond. The personal dependence of the peasant was expressed in humiliating customs and rituals, showing the superiority of the master over the mob. The serfs were obliged to perform corvée for the lord - to work in his fields. Corvée was very difficult, although many of the duties of serfs seem quite harmless to us today: for example, the custom of giving the lord a goose for Christmas, and a basket of eggs for Easter. However, when the patience of the peasants came to an end and they took up pitchforks and axes, the rebels demanded, along with the abolition of corvée, the abolition of these duties, which humiliated their human dignity.

"Agricultural work" / plowing). Miniature from the 14th century.

By the end of the Middle Ages there were not so many serf peasants left in Western Europe. Peasants were freed from serfdom by free city-communes, monasteries and kings. Many feudal lords also understood that it was wiser to build relationships with peasants on a mutually beneficial basis, without oppressing them excessively. Only extreme need and the impoverishment of European chivalry after 1500 forced the feudal lords of some European countries to launch a desperate attack on the peasants. The purpose of this offensive was the restoration of serfdom, “second edition

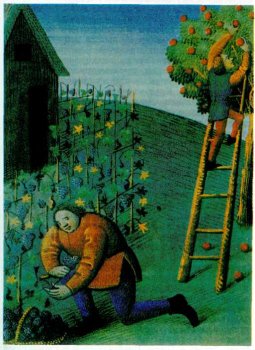

"Vintage". From a medieval miniature of the 13th century.

serfdom,” but in most cases the feudal lords had to be content with driving peasants off the land, seizing pastures and forests, and restoring some ancient customs. Peasants Western Europe responded to the onslaught of the feudal lords with a series of formidable uprisings and forced their masters to retreat.

The main enemies of the peasants in the Middle Ages were not feudal lords, but hunger, war and disease. Hunger was a constant companion of the villagers. Once every 2-3 years there was always a shortage of crops in the fields, and once every 7-8 years the village was visited by real famine, when people ate grass and tree bark, scattered in all directions, begging. Part of the village population died out in such years; It was especially hard for children and the elderly. But even in fruitful years, the peasant’s table was not bursting with food - his food consisted mainly of vegetables and bread. Residents of Italian villages took lunch with them to the field, which most often consisted of a loaf of bread, a slice of cheese and a couple of onions. Peasants did not eat meat every week. But in the fall, carts loaded with sausages and hams, wheels of cheese and barrels of good wine pulled from the villages to the city markets and to the castles of the feudal lords. The Swiss shepherds had a rather cruel, from our point of view, custom: the family sent their teenage son alone to the mountains to herd goats for the whole summer. They didn’t give him any food from home (only sometimes the compassionate mother, secretly from his father, slipped a piece of flatbread into his son’s bosom for the first days). The boy drank goat's milk for several months, ate wild honey, mushrooms and generally everything that he could find edible in the alpine meadows. Those who survived under these conditions became so big after a few years that all the kings

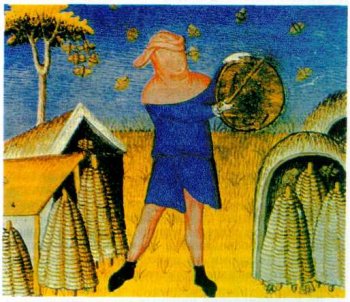

"Beekeeping". Medieval miniature of the 15th century.

Europe sought to replenish its guards exclusively with the Swiss. The period from 1100 to 1300 was probably the brightest in the life of the European peasantry. The peasants plowed more and more land, used various technical innovations in cultivating fields, and learned gardening, horticulture and viticulture. There was enough food for everyone, and the population of Europe was rapidly increasing. Peasants who could not find anything to do in the countryside went to the cities and engaged in trade and crafts there. But by 1300, the possibilities for developing the peasant economy were exhausted - there was no more undeveloped land, old fields were depleted, cities increasingly closed their gates to uninvited strangers. It became increasingly difficult to feed themselves, and the peasants, weakened by poor nutrition and periodic hunger, became the first victims of infectious diseases. The plague epidemics that tormented Europe from 1350 to 1700 showed that the population had reached its limit and could no longer increase.

At this time, the European peasantry was entering a difficult period in its history. Dangers come from all sides: in addition to the usual threat of famine, there are also diseases, the greed of royal tax collectors, and attempts at enslavement by the local feudal lord. The villager has to be extremely careful if he wants to survive in these new conditions. It’s good to have few hungry mouths in the house, which is why peasants of the late Middle Ages got married late and had children late. In France in the XVI-XVII centuries. There was such a custom: a son could bring a bride to his parents’ house only when his father or mother was no longer alive. Two families could not sit on the same plot of land - the harvest was barely enough for one couple with its offspring.

The caution of the peasants was manifested not only in planning their family life. Peasants, for example, were distrustful of the market and preferred to produce the things they needed themselves rather than buy them. From their point of view, they were certainly right, because price surges and the tricks of urban merchants made the peasants too dependent and risky on market affairs. Only in the most developed areas of Europe - Northern Italy, the Netherlands, lands on the Rhine, near cities such as London and Paris - have peasants been living since the 13th century. actively traded agricultural products in the markets and bought the handicrafts they needed there. In most other regions of Western Europe, rural residents until the 18th century. produced everything they needed on their own farms; They came to the markets only occasionally to pay the rent to the lord with the proceeds.

Before the emergence of large capitalist enterprises that produced cheap and high-quality clothing, shoes, and household items, the development of capitalism in Europe had little impact on peasants living in the outbacks of France, Spain or Germany. He wore homemade wooden shoes, homespun clothes, illuminated his home with a torch, and often made dishes and furniture himself. These home craft skills, long preserved among the peasants, began in the 16th century. used by European entrepreneurs. Guild regulations often prohibited the establishment of new industries in cities; then rich merchants distributed raw materials for processing (for example, combing yarn) to residents of surrounding villages for a small fee. The contribution of peasants to the development of early European industry was considerable, and we are only now beginning to truly appreciate it.

Despite the fact that they had to do business with city merchants, willy-nilly, the peasants were wary not only of the market and the merchant, but also of the city as a whole. Most often, the peasant was interested only in the events that took place in his native village, and even in two or three neighboring villages. During Peasant War in Germany, detachments of villagers each acted in the territory of their own small district, thinking little about the situation of their neighbors. As soon as the troops of the feudal lords hid behind the nearest forest, the peasants felt safe, laid down their arms and returned to their peaceful pursuits.

The life of a peasant was almost independent of the events that took place in big world" - the crusades, changes of rulers on the throne, disputes between learned theologians. It was much more influenced by the annual changes that occurred in nature - the change of seasons, rains and frosts, deaths and offspring of livestock. The peasant’s circle of human contacts was small and limited to a dozen or two familiar faces, but constant communication with nature gave the villager a rich experience of emotional experiences and relationships with the world. Many of the peasants subtly felt the charm of the Christian faith and pondered intensely about the relationship between man and God. The peasant was not at all a stupid and illiterate idiot, as he was portrayed by his contemporaries and some historians many centuries later.

Middle Ages for a long time treated the peasant with disdain, as if not wanting to notice him. Wall paintings and book illustrations of the 13th-14th centuries. Peasants are rarely depicted. But if artists draw them, then they must be at work. The peasants are clean and neatly dressed; their faces are more like the thin, pale faces of monks; lined up, the peasants gracefully swing their hoes or flails to thresh grain. Of course, these are not real peasants with faces weathered from constant work in the air and clumsy fingers, but rather their symbols, pleasing to the eye. European painting has noticed the real peasant since about 1500: Albrecht Dürer and Pieter Bruegel (nicknamed “The Peasant”) begin to depict peasants as they are: with rough, semi-animal faces, dressed in baggy, ridiculous outfits. The favorite subject of Bruegel and Dürer is peasant dances, wild, similar to bear trampling. Of course, there is a lot of mockery and contempt in these drawings and engravings, but there is something else in them. The charm of energy and enormous vitality emanating from the peasants could not leave the artists indifferent. The best minds in Europe are beginning to think about the fate of those people who held on their shoulders

a brilliant society of knights, professors and artists: not only jesters entertaining the public, but also writers and preachers begin to speak the language of peasants. Saying goodbye to the Middle Ages, European culture for the last time showed us a peasant who was not at all bent over at work - in the drawings of Albrecht Durer we see peasants dancing, secretly talking about something with each other, and armed peasants.