People at all times had to protect themselves and their property from the encroachments of their neighbors, and therefore the art of fortification, that is, the construction of fortifications, is very ancient. In Europe and Asia you can see everywhere fortresses built in antiquity and the Middle Ages, as well as in the New and even Modern times. It may seem that a castle is just one of all the other fortifications, but in reality it is very different from the fortifications and fortresses that were built in previous and subsequent times. The large Celtic “dunes” of the Iron Age, built on the hills of Ireland and Scotland, and the “campuses” of the ancient Romans were fortifications, behind whose walls in case of war the population and armies took refuge with all their property and livestock. The "burghs" of Saxon England and the Teutonic countries of continental Europe served the same purpose. Ethelfreda, daughter of King Alfred the Great, built the burgh of Worcester as a "refuge for all the people." The modern English words "borough" and "burgh" are derived from this ancient Saxon word "burn" (Pittsburgh, Williamsburg, Edinburgh), just as the names Rochester, Manchester, Lancaster are derived from the Latin word "castra", which means "fortified camp" . These fortresses should in no way be compared to a castle; The castle was a private fortress and the home of the lord and his family. In European society during the late Middle Ages (1000-1500), a period that can rightfully be called the era of castles or the era of chivalry, the rulers of the country were lords. Naturally, the word "lord" is used only in England, and it comes from the Anglo-Saxon word hlaford. Hlaf- this is “bread”, and the whole word means “distributing bread”. That is, this word was used to describe a good father-intercessor, and not a martinet with iron fists. In France, such a lord was called seigneur, in Spain senor, in Italy Signor, Moreover, all these names are derived from the Latin word senior which means “elder” in translation, in Germany and the Teutonic countries the lord was called Herr, Heer or Her.

The English language has always been distinguished by great originality in word formation, as we have already seen in the example of the word knight. The interpretation of the sovereign lord as a lord distributing grain was generally true for Saxon England. It must have been difficult and bitter for the Saxons to call this name the new powerful Norman lords who began to rule England starting in 1066. Exactly these lords built the first large castles in England, and until the 14th century, the lords and their knightly retinue spoke exclusively Norman-French. Until the 13th century they considered themselves French; most of them owned lands and castles in Normandy and Brittany, and the very names of the new rulers came from the names of French cities and villages. For example, Baliol is from Bellieu, Sachevreul is from Saute de Chevreuil, as well as the names Beauchamp, Beaumont, Bur, Lacy, Claire, etc.

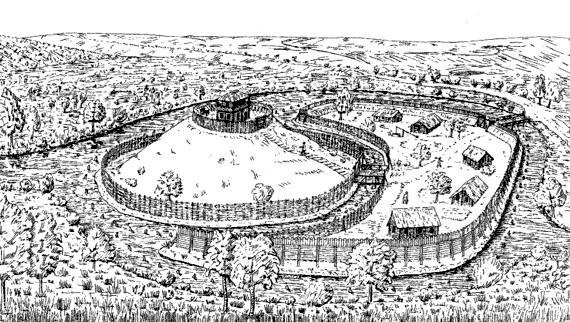

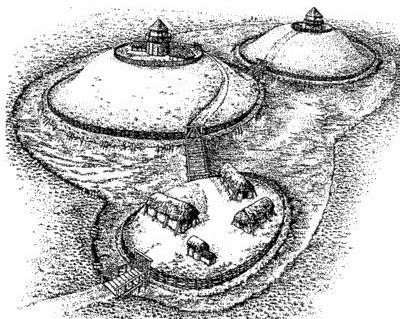

The castles that are so familiar to us today bear little resemblance to the castles that the Norman barons built for themselves, both in their own country and in England, since they were usually built from wood rather than stone. There are several early stone castles (the great tower of the Tower of London is one of the surviving examples of such architecture, almost unchanged), built at the end of the 11th century, but the great era of stone castle building did not begin until about 1150. The defensive structures of early castles were earthen ramparts, the appearance of which has changed little in the two hundred years that have passed since the construction of such fortifications began on the continent. The world's first castles were built in the Frankish kingdom to protect against Viking raids. Castles of this type were earthen structures - an oblong or rounded ditch and an earthen rampart, surrounding a relatively small area, in the center or on the edge of which there was a high mound. The earthen rampart was topped with a wooden palisade. The same palisade was placed on the top of the hill. They built a fence inside wooden house. Apart from the mound, these buildings are very reminiscent of the pioneer homes of the American Wild West.

At first, this type of castle dominated. The main structure, raised on an artificial hill, was later surrounded by a moat and an earthen rampart with a palisade. Inside the area, bounded by a rampart, there was a castle courtyard. The main building, or citadel, stood on top of an artificial, rather high hill on four powerful corner pillars, due to which it was raised above the ground. Below is a description of one of these castles, given in the biography of Bishop John of Terouen, written around the year: “Bishop John, traveling around his parish, often stopped in Marcham. Near the church there was a fortification, which can rightfully be called a castle. It was built according to the custom of the country by a former lord of the area many years ago. Here where the noble people are most They spend their lives in wars and have to defend their homes. To do this, they fill up a mound of earth as high as possible, and surround it with a ditch, as wide and deep as possible. The top of the hill is surrounded by a very strong wall of hewn logs, with small towers placed around the circumference of the fence - as many as funds allow. A house or large building is placed inside the fence, from where one can observe what is happening in the surrounding area. You can enter the fortress only through a bridge that starts from the counter-scarp of the ditch, supported by two or even three pillars. This bridge goes up to the top of the hill.” The biographer further tells how one day, when the bishop and his servants were climbing the bridge, it collapsed, and people fell from a height of thirty-five feet (11 meters) into a deep ditch.

The height of the mound was usually from 30 to 40 feet (9-12 meters), although there were exceptions - for example, the height of the hill on which one of the Norfolk castles near Thetford was placed reached hundreds of feet (about 30 meters). The top of the hill was made flat and the upper palisade surrounded a courtyard of 50-60 square yards. The extent of the yard varied from one and a half to 3 acres (less than 2 hectares), but was rarely very large. The shape of the castle territory varied - some were oblong, some were square, and there were courtyards in the shape of a figure eight. Variations were highly variable depending on the size of the host condition and site configuration. After the site for construction was chosen, the first step was to dug it in with a ditch. The excavated earth was thrown onto the inner bank of the ditch, resulting in a rampart, an embankment called with scrape. The opposite bank of the ditch was called, accordingly, the counter-scarp. If possible, a ditch was dug around a natural hill or other elevation. But as a rule, the hill had to be filled in, which required a huge amount of earthwork.

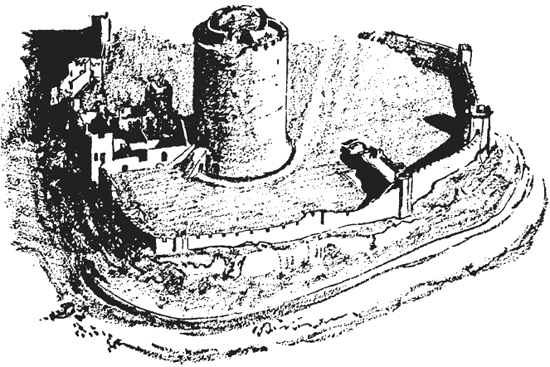

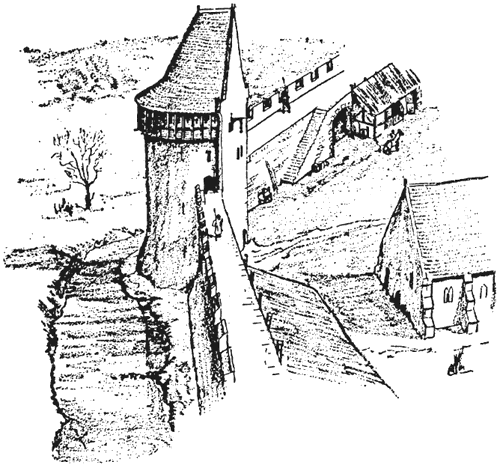

Rice. 8. Reconstruction of the 11th century castle with a mound and courtyard. The yard, which in this case is a separate enclosed area, is surrounded by a palisade of thick logs and surrounded on all sides by a ditch. The hill, or mound, is surrounded by its own separate ditch, and at the top of the hill there is another palisade around a tall wooden tower. The citadel is connected to the courtyard by a long suspension bridge, the entrance to which is protected by two small towers. The upper part of the bridge is liftable. If the attacking enemy captured the courtyard, then the defenders of the castle could retreat across the bridge behind the palisade at the top of the embankment. The lifting part of the suspension bridge was very light, and retreaters could simply throw it down and lock themselves behind the upper palisade.

These were the castles built everywhere in England after 1066. One of the tapestries, woven a little later than the event depicted, shows Duke William's men - or, more likely, Saxon slaves collected from the area - building the mound of Hastings Castle. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 1067 tells how “the Normans built their castles throughout the country and oppressed the poor people.” In the book doomsday there is a record of houses that had to be demolished to build castles - for example, 116 houses were demolished in Lincoln and 113 in Norwich. It was precisely such easily erected fortifications that the Normans needed at that time in order to consolidate their victory and subjugate the hostile English, who could quickly gather their strength and rebel. It is interesting to note the fact that when a hundred years later the Anglo-Normans, under the leadership of Henry II, tried to conquer Ireland, they built exactly the same castles on the conquered lands, although in England itself and on the continent large stone castles had already replaced the old wooden-earth fortifications with mounds and palisades.

Some of these stone castles were completely new and built on new sites, while others were rebuilt old castles. Sometimes the main tower was replaced with a stone one, leaving the wooden palisade surrounding the castle courtyard intact; in other cases, a stone wall was built around the castle courtyard, leaving the wooden tower on the top of the embankment intact. For example, in York, the old wooden tower stood for two hundred years after a stone wall was built around the courtyard, and only Henry III, between 1245 and 1272, replaced the wooden main tower with a stone one, which remains to this day. In some cases, new stone main towers were built on top of old hills, but this only happened when the old castle was built on a natural hill. An artificial hill, built just a hundred years ago, could not withstand the heavy weight of a stone building. IN in some cases, when a man-made hill had not settled sufficiently at the time of construction, a tower was erected around the hill, incorporating it into a larger foundation, as, for example, at Kenilworth. In other cases, a new tower was not built on the top of the hill, but instead the old palisade was replaced with stone walls. Residential buildings, outbuildings, etc. were erected inside these walls. Such buildings are now called fencing(shell keeps) - a typical example is the Round Tower of Windsor Castle. The same ones are well preserved in Restormel, Tamworth, Cardiff, Arundel and Carisbrooke. The outer walls of the courtyard supported the slopes of the hill, preventing them from sliding, and were connected on all sides with the walls of the upper fence.

For England, the main buildings of castles in the form of towers are more typical. In the Middle Ages, this building, this main part of the citadel, was called a donjon or simply a tower. First word in English language has changed its meaning, because in our time, when you hear the word “donjon”, you imagine not the main tower of a castle citadel, but a gloomy prison. And naturally, the Tower of London retained its former historical name.

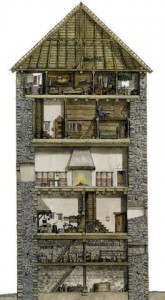

The main tower formed the core, the most fortified part of the castle's citadel. On the ground floor there were storage rooms for most of the food supplies, as well as an arsenal where weapons and military equipment were stored. Above were the guard quarters, kitchens and living quarters for the soldiers of the castle garrison, and on the top floor lived the lord himself, his family and retinue. The military role of the castle was purely defensive, since in this impregnable nest, behind incredibly strong and thick walls, even a small garrison could hold out as long as supplies of food and water allowed. As we will see later, there were times when the main towers of the citadel were subjected to enemy assault or were damaged so that they became unsuitable for defense, but this happened extremely rarely; usually castles were captured either as a result of treason, or the garrison surrendered, unable to withstand hunger. Problems with water supply rarely arose, since there was always a source of water in the castle - one such source can still be seen today in the Tower of London.

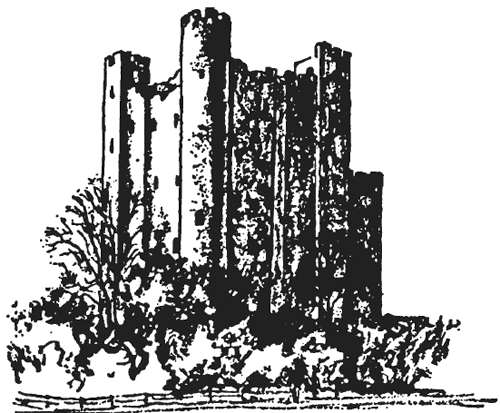

Rice. 9. Pembroke Castle; shows a large cylindrical keep built in 1200 by William Marshal.

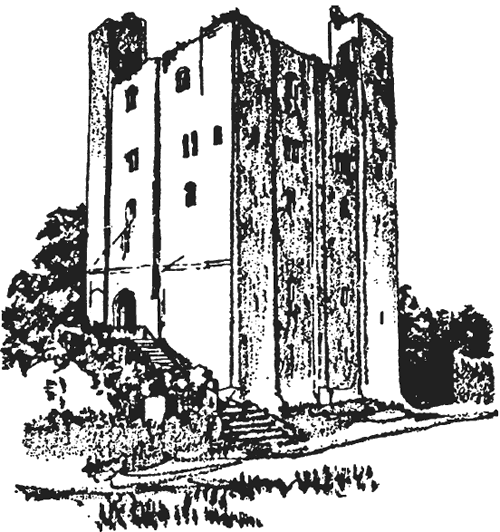

Enclosures were quite common, probably because they were the easiest way to rebuild an existing castle with a courtyard and mound, but the most typical feature of a medieval, and particularly English, castle is the large quadrangular tower. It was the most massive structure that was part of the castle buildings. The walls were gigantic in thickness and were installed on a powerful foundation capable of withstanding the blows of pickaxes, drills and battering guns of the besiegers. The height of the walls from the base to the jagged top averaged 70-80 feet (20-25 meters). Flat buttresses, called pilasters, supported the walls along their entire length and at the corners; at each corner such a pilaster was crowned with a turret on top. The entrance was always located on the second floor, high above the ground. An external staircase led to the entrance, located at right angles to the door and covered by a bridge tower installed outside directly against the wall. For obvious reasons, the windows were very small. On the first floor there were none at all, on the second they were tiny and only on the next floors they became a little larger. These distinctive features - the bridge tower, the outer staircase and small windows - can be clearly seen at Rochester Castle and at Hedingham Castle in Essex.

The walls were made of rough stones or rubble, lined with cut stone inside and out. These stones were well processed, although more in rare cases the external cladding was also made of rough stones, for example in the white Tower of London. At Dover, a castle built by Henry II in 1170, the walls are 21-24 feet (6-7 meters) thick; at Rochester they are 12 feet (3.7 meters) thick at the base, gradually decreasing to 10 feet at the roof. (3 meters). The upper, non-hazardous parts of the walls were usually somewhat thinner - their thickness decreased on each subsequent floor, allowing a little gain in space, reducing the weight of the building and saving construction material. In the towers of such large castles as London, Rochester, Colchester, Hedingham and Dover, the internal volume of the building was divided in half by a thick transverse wall that ran through the entire structure from top to bottom. The upper parts of this wall were lightened by numerous arches. Such transverse walls increased the strength of the building and made it easier to lay floors and build roofs, since they reduced the spans that had to be covered. In addition, transverse walls were also beneficial from a purely military point of view. For example, in Rochester in 1215, when King John was besieging the castle, his sappers dug under the north-west corner of the main tower and it collapsed, but the defenders of the castle moved to the other half, separated by a transverse wall, and held out for some time.

The more massive and taller main towers were divided into a basement and three upper floors; in smaller castles, two floors were built on the base, although there are, of course, exceptions. For example, Corfe Castle - very high - had only two upper floors, just like Guildford, but Norham Castle had four upper floors. Some castles, such as Kenilworth, Rising and Middleham - all of which looked long in plan and not particularly high - had only a basement and one upper floor.

Rice. 10. Main tower of Rochester Castle, Kent. Built in 1165 by King Henry II, the castle, besieged by King John in 1214, was taken after the north-west corner tower was excavated. The modern round turret was built to replace the one that had collapsed by Henry III (the original text says that this happened in 1200, which is impossible, since Henry was born in 1207 - Transl.). The bridgehead tower is visible on the right of the picture.

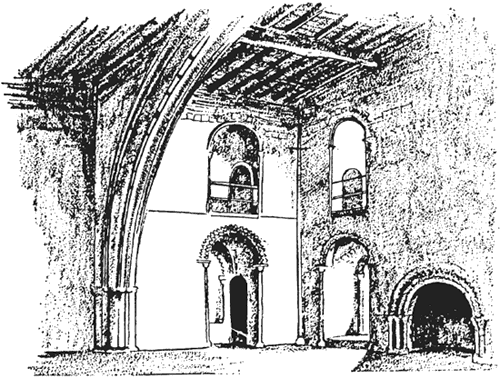

Each floor was one large room, divided in two if the castle had a transverse wall. The ground floor was used for storerooms: provisions for the garrison and fodder for horses, food for servants, as well as weapons and various military equipment were stored there, among other things necessary to ensure the functioning of the castle in times of peace and war - stones and wood for repairs, paints, lubricants, leather, ropes, bales of fabrics and linens, and probably supplies of quicklime and fuel oil that were poured on the heads of the besiegers. Often the top floor was divided into smaller rooms by wooden walls, and in some castles, such as Dover or Hedingham, the main room - the hall on the second floor - was made double-height; the hall had a very high vault, and there were galleries along the walls. (The main tower of the castle in Norwich, where the museum is now located, is arranged in exactly this way and allows you to understand what it looked like in real life.) In the larger main towers, fireplaces were installed on the upper floors, many of the early examples of which survive to this day.

Rice. 11. The main building of Hedingham Castle in Essex, built in 1100. On the left side of the picture you can see the stairs leading to the front door. Originally, as in Rochester, this staircase was covered by a tower.

Stairs leading to all floors of the main building were located in its corners; they led from the ground floor to the turrets and out onto the roof. The stairs were spiral, twisting clockwise. This direction was not chosen by chance, since the defenders of the castle had to fight on the stairs if the enemy broke into the castle. In this case, the defenders had an advantage: naturally, they tried to push the enemy down, while left hand with a shield rested against the central pillar of the stairs, and for right hand, which acted as a weapon, there was enough space left even on the narrow stairs. The attackers were forced, overcoming resistance, to make their way up, while their weapons constantly collided with the central pillar. Try to imagine this situation when you find yourself on a spiral staircase, and you will understand what I mean.

Rice. 12. The main hall of Hedingham Castle in Essex. The arch, stretching from left to right in the figure, represents the upper part of the transverse wall, dividing the volume of the castle into two halves. The cross wall, very thick on the ground floor, turns into an arch on the upper floor, which helps lighten the weight of the building and make the main hall more spacious.

On the upper floors of the main building, many small rooms were built directly into the wall. These were private quarters, rooms in which the lord of the castle, his family and guests slept; latrines were also located deep within the walls. The toilets are very cleverly designed; medieval ideas about sanitation and hygiene are not as primitive as we tend to think. The latrines of medieval castles were more comfortable than the latrines still found in rural areas, and they were also easier to keep clean. The toilets were small rooms protruding from the outer wall. The seats were made of wood; they were located above a hole that opened outward. All, so to speak, waste, like in trains, poured directly onto the street. Dressing rooms in those days were evasively called wardrobes (translated from French, “wardrobe” literally means “take care of the dress”). In Elizabethan times, the euphemism for privy was the word "jake", just as we in America call a privy "john", and the English use the word "lu" for the same purpose.

The spring or spring was extremely important to the survival of the inhabitants and defenders of the castle. Sometimes, as was the case in the Tower, the source was located in the basement, but more often it was brought to the living quarters - it was more reliable and more convenient. Another feature of the castle, which at that time was considered absolutely necessary, was the house church or chapel, which was located in the tower in case the defenders were cut off from the courtyard if it was captured by the enemy. An excellent example of a chapel is located in the main tower of the white Tower of London, but more often chapels were located at the top of the porch that covered the front door.

At the end of the 12th century, important changes were planned in the architecture of the main tower of the castle. The towers, rectangular in plan, despite the fact that they were very massive, had one significant drawback - sharp corners. The enemy, remaining practically invisible and inaccessible (you could only shoot from the turret located at the top of the corner), could methodically remove stones from the wall, destroying the castle. In order to end this inconvenience and reduce the risk, round towers began to be built, such as the main tower of Pembroke Castle, built in 1200 by William Marshal. Some towers had an intermediate, transitional appearance, so to speak, a compromise between the old rectangular design and the new cylindrical one. These were polygonal towers with obtuse beveled corners. Examples include the towers of Orford Castle in Suffolk and Conisborough Castle in Yorkshire, the former built by King Henry II between 1165 and 1173, and the latter by Earl Hamlin of Warenne in the 1290s.

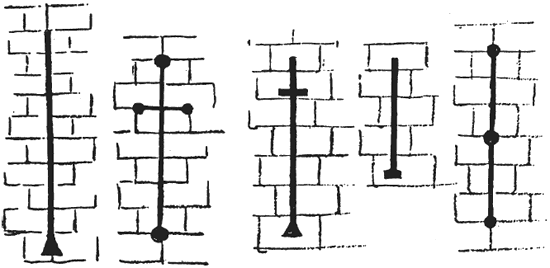

The stone walls that replaced the old palisades around the castle courtyards were built based on the same military engineering considerations as the main towers. The walls were built as high and as thick as possible. The lower part was usually wider than the upper part in order to provide strength to the most vulnerable section of the wall, and also to make the surface of the wall sloping so that stones and other throwing weapons thrown from above would bounce off the lower part, ricochet and hit the besieging enemy more strongly. The wall was crenellated, that is, it was crowned with structural elements, which we now call loopholes, located between the battlements. Such a wall with loopholes was constructed as follows: along the top of the wall there was a fairly wide passage or platform, which Latin called alatorium, from which it came English word allure- wall balustrade. On the outside, the balustrade was protected by an additional wall 7 to 8 feet high (about 2.5 meters), interrupted at equal distances by transverse slot-like openings. These openings were called embrasures, and the sections of the parapet between them were called Merlons, or teeth. The openings allowed the castle defenders to shoot at the attackers or drop various projectiles on them. True, for this, the defenders had to show themselves to the enemy for some time before hiding again behind the battlement. To reduce the risk of defeat, narrow slits were often made in the battlements, through which the defenders could shoot from bows while being in cover. These slots were located vertically in a wall or in a battlement, were no more than 2-3 inches (5-8 centimeters) wide on the outside, and were wider on the inside to make it easier for the shooter to manipulate the weapon. Such shooting slots were up to 6 feet (2 meters) high and were equipped with an additional transverse slot just above half the height of the slot. These transverse slits were intended to allow the shooter to throw arrows in lateral directions at an angle of up to forty-five degrees to the wall. There were many designs of such slots, but in essence they were all the same. One can imagine how difficult it was for an archer or crossbowman to hit such a narrow gap with an arrow; but if you visit any castle and stand at the shooting slot, you will see how clearly the battlefield is visible, what an excellent view the defenders had and how convenient it was for them to shoot through these slots with a bow or crossbow.

Rice. 13. Reconstruction of the flank tower and wall of the castle courtyard of the 13th century. The tower is cylindrical on the outside and flat on the inside. On the inside of the tower you can see that a small lift sticks out of the wall, with the help of which ammunition was supplied to the defenders who were behind the fence inside the platform on the tower. The high roof is made of thick wooden rafters covered with tiles, flat stones or slate. The crown of the tower under the roof is surrounded by a wooden fence. One can imagine that the attackers, having overcome the ditch filled with water, came under fire from archers located in the tower at its top and behind the gallery fence. The pedestrian area at the top of the wall is shown, as well as the buildings adjacent to the wall in the castle courtyard.

Of course, the flat wall surrounding the castle has a lot of disadvantages, since if the attackers got to its foot, they became inaccessible to the defenders. Anyone who dared to lean out of the embrasure would be immediately shot, but anyone who remained under the protection of the battlements would not be able to cause any harm to the attackers. Therefore, the best solution was to dismember the wall and build watchtowers or bastions along its perimeter at equal intervals, which protruded forward, beyond the plane of the wall into the field, and through rifle slits in their walls, the defenders were able to shoot from loopholes in all directions, that is, shooting through the enemy in the longitudinal direction, along the enfilade, as they expressed it in those days. At first, such towers were rectangular, but then they began to be erected in the form of half-cylinders protruding from the outer side of the walls, while the inner side of the bastion was flat and did not protrude beyond the plane of the wall of the castle courtyard. The bastions rose above the upper edge of the wall, dividing the pedestrian parapet into sectors. The path continued through the tower, but if necessary it could be blocked by a massive wooden door. Therefore, if some detachment of attackers managed to penetrate the wall, then it could be cut off in a limited section of the wall and destroyed.

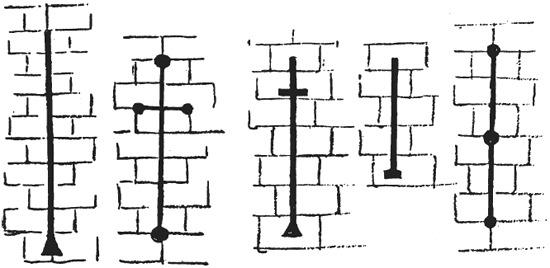

Rice. 14. Different types of shooting slits. In many castles, rifle slits were located in various parts of them. different shapes. Most slits had an additional transverse slot, which allowed the archer to shoot not only directly in front of him, but also in lateral directions at an acute angle to the wall. However, they also made slits that did not have a transverse part. The height of the rifle slits ranged from 1.2 to 2.1 meters.

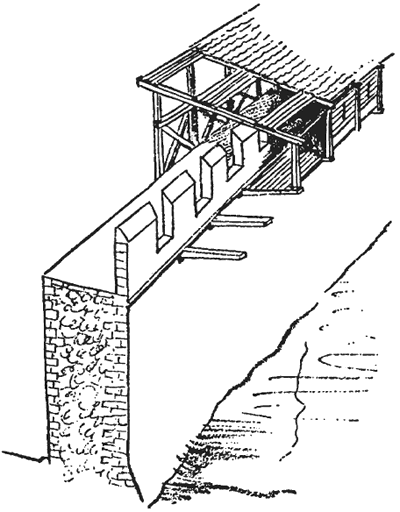

Castles seen in England today are usually flat topped and unroofed. The top edge of the walls is also flat, except for the battlements, but in those days when castles were used for their intended purpose, the main towers and bastions often had steep roofs, which can still be seen today in the castles of continental Europe. We tend to forget, looking at such dilapidated castles as Usk in Dover or Conisborough, which did not withstand the onslaught of inexorable time, how they were covered with wooden roofs. Very often, the upper part - parapets and walkways - of walls, bastions and even main towers was crowned with long wooden covered galleries, which were called fences, or in English hoarding(from the Latin word hurdicia), or sail. These galleries extended beyond the outer edge of the wall by approximately 6 feet (about 2 meters), and holes were made in the floor of the galleries to allow the attackers at the foot of the wall to be shot through, stones to be thrown at the attackers, and boiling oil or boiling water to be poured on their heads. The disadvantage of such wooden galleries was their fragility - these structures could be destroyed using siege engines or set on fire.

Rice. 15. The diagram shows how fences, or “lintels,” were attached to the walls of the castle. They were probably placed only in cases where the castle was threatened with siege. In many castle courtyard walls you can still see square holes in the walls under the battlements. Beams were inserted into these holes, onto which a fence with a covered gallery was placed.

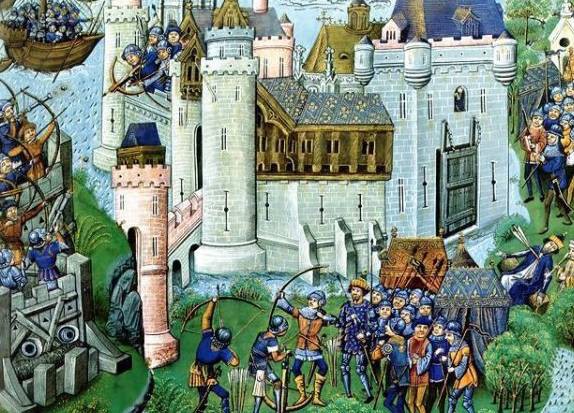

The most vulnerable part of the wall surrounding the castle courtyard was the gate, and at first close attention was paid to the defense of the gate. The earliest way to protect a gate was to place it between two rectangular towers. A good example of this type of protection is the construction of gates in the 11th century Exeter Castle, which has survived to this day. In the 13th century, the square gate towers gave way to the main gate tower, which was a merger of the two previous ones with additional floors built above them. These are the gate towers of Richmond and Ludlow Castles. In the 12th century, the more common way to protect the gate was to build two towers on either side of the entrance to the castle, and only in the 13th century did gate towers appear in their completed form. The two flanking towers now join into one above the gate, becoming a massive and powerful fortification and one of the most important parts of the castle. The gate and entrance now turn into a long and narrow passage, blocked at each end porticles. These were doors that slid vertically along gutters carved in stone, made in the form of large gratings made of thick timber, the lower ends of the vertical beams were pointed and bound with iron, thus the lower edge porticles was a series of sharpened iron stakes. These lattice gates were opened and closed using thick ropes and a winch located in a special chamber in the wall above the passage. In the “bloody tower” of the Tower of London you can still see portico with a functioning lifting mechanism. Later, the entrance was protected with the help of "mertières", deadly holes drilled into the vaulted ceiling of the passage. Through these holes, objects and substances common in such a situation - arrows, stones, boiling water and hot oil - rained down and poured on anyone who tried to force their way through to the gate. However, another explanation seems more plausible - water was poured through the holes if the enemy tried to set fire to the wooden gates, since the best way to penetrate the castle was to fill the passage with straw, logs, thoroughly soak the mixture with flammable oil and set it on fire; they killed two birds with one stone - they burned the lattice gates and fried the castle defenders in the gate rooms. In the walls of the passage there were small rooms equipped with rifle slits, through which the defenders of the castle could use their bows to shoot at close range the dense mass of attackers who were trying to break into the castle.

In the upper floors of the gate tower there were rooms for soldiers and often even living quarters. In special chambers there were gates, with the help of which the drawbridge was lowered and raised on chains. Since the gate was the place that was most often attacked by the enemy besieging the castle, they were sometimes provided with another means of additional protection - the so-called barbicans, which began at some distance from the gate. Typically, the barbican consisted of two high, thick walls running parallel outward from the gate, thus forcing the enemy to squeeze into the narrow passage between the walls, exposing himself to the arrows of the archers of the gate tower and the upper platform of the barbican hidden behind the battlements. Sometimes, to make access to the gate even more dangerous, the barbican was installed at an angle to it, which forced attackers to go to the gate on the right, and parts of the body not covered by shields became targets for archers. The entrance and exit of the Barbican were usually very intricately decorated. At Goodrich Castle near Herfordshire, for example, the entrance was made in the form of a semicircular vault, and the two barbicans covering the gates of Conway Castle looked like small castle courtyards.

Rice. 16. Reconstruction of the gates and barbican of the Arc Castle in France. The Barbican is a complex structure with two drawbridges covering the main entrance.

The Gate Keep, built in the mid-14th century by Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick (grandfather of Earl Richard), is a good example of a compact watchtower and barbican combined into a superbly designed ensemble. The gate tower is built in the traditional plan of two towers connecting at the top over a narrow passage, it has three additional floors with tall crenellated turrets at each corner, rising above the battlements of the walls. Ahead, outside the castle, two battlements form another narrow passage leading to the castle; at the far end of these barbican walls, beyond them, there are two more towers - smaller copies of the gate tower. In front of them is a drawbridge over a water-filled moat. This means that the attackers, in order to break through to the gate, first had to use fire or sword to make their way through the raised drawbridge, which blocked the path to the first gate and the porticoes located behind them. Then they would have to fight their way through the narrow passage of the Barbican. After this, finally finding themselves in front of the gate itself, the attackers would be forced to cross the second ditch, break through the next raised bridge and porticoes. Having accomplished these feats, the enemy found himself in a narrow corridor, showered with arrows and doused with boiling water and hot oil from numerous mertiers and rifle slits in the side walls, and at the end of the enemy’s path the following porticoes awaited. But the most interesting thing about the design of this gate tower was the truly scientific way in which the battlements, arranged in steps, covered each other. First came the walls and turrets of the barbican, behind them and above them rose the walls and roof of the gate tower, over which the corner turrets of the gate tower dominated, the first pair was located below the second, from each subsequent shooting platform it was possible to cover the one located in front below. The turrets of the gate fortification were connected by transitional hanging arched stone bridges, so the defenders did not have to go down to the roof to move from one turret to another.

Today, when you enter the gate leading to the courtyard and main tower of a castle such as Warwick, Dover, Kenilworth or Corfe, you cross a large expanse of mown grass in the courtyard. But everything here was different in those days when the castle was used for its intended purpose! The entire space of the courtyard was filled with buildings - most of them were wooden, but there were also stone houses among them. Along the walls of the courtyard there were numerous covered rooms - some stood next to the wall, some were built directly into its thickness; there were stables, kennels, cowsheds, all kinds of workshops - masons, carpenters, gunsmiths, blacksmiths (a gunsmith should not be confused with a blacksmith - the first was a highly qualified specialist), sheds for storing straw and hay, dwellings for a whole army of servants and hangers-on, open kitchens, dining rooms , stone rooms for hunting falcons, a chapel and a large hall - more spacious and spacious than in the main tower of the castle. This hall, located in the courtyard, was used during the days of peace. Instead of grass, there was tightly compacted earth or areas paved with cobblestones or even paving stones, or, in a very few castles, the courtyard was covered with a mess of impassable mud. Instead of tourists idly resting in the shadow of the ruins, people constantly walked here, busy with their daily work. Food preparation took place almost continuously, horses were fed, watered and trained all the time, cattle were driven into the yard for milking and driven out of the castle to pasture, gunsmiths and blacksmiths repaired armor for the owner and soldiers of the garrison, shoed horses, forged iron objects for the needs of the castle , carts and carts were being repaired - there was an incessant noise of continuous work.

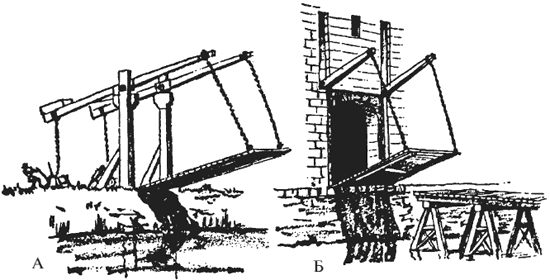

Rice. 17. The figure shows one of the methods for constructing a drawbridge.

A. An open drawbridge, such as the Barbican Bridge at Arc Castle. The bridge is attached by a chain to two powerful horizontal beams, each of which is hinged to the tops of pillars dug vertically into the ground. The chains attached to the edges of the bridge, with their other ends, were attached to the outer ends of the horizontal beams, and weights were attached to their opposite ends that balanced the weight of the bridge. These rear ends of the weighted horizontal bars were connected to winches by chains. Since the weights balanced the weight of the bridge, two people could easily lift it. B. This picture shows the drawbridge located in front of the castle gate itself. The principle of its operation is the same. The inner, weighted ends of the horizontal beams are located behind the walls of the castle; the beams themselves are passed through holes in the wall directly above the entrance. The outer ends protrude beyond the walls. When the bridge was raised, the horizontal beams were placed in special slots in the wall and sunk flush with the wall; in the same way, the bridge deck lay in a special recess in the wall, and its plane in the raised state merged with the outer surface of the wall. Some drawbridges were simpler - they were raised on chains attached to the outer edge of the bridge deck, passed through holes in the wall and wound on a winch gate. True, lifting such a bridge required great physical effort due to the lack of a counterweight.

The huntsmen and grooms were also busy all the time, since there was a whole army of animals in the castle - dogs, falcons, hawks and horses, which had to be looked after and trained and trained in preparation for hunting. Every day, parties of deer or small game hunters - hares and rabbits - were sent from the castle, and sometimes expeditions of wild boar hunters were equipped. There were also people who liked to hunt birds with falcons. Hunting, driven or falconry, which was apparently the main component of the leisure of high society of the time, was a much more important part of everyday life than we tend to think. With such a rush of eaters living in the castle, all the game caught in the hunt went into the cauldron.

Despite the fact that the type of castle with a courtyard and a main tower was the main one in continental Europe and in England throughout the Middle Ages, one should not think that this type was the only one. The diversity stemmed from the fact that during the 13th century, castles began to undergo reconstruction and improvements in order to keep up with progress in siege art and innovations in methods of defending fortresses. For example, Richard the Lionheart was an excellent military engineer; It was he who introduced many new ideas into practice, rebuilding such previously built castles as Tower of London, and implementing all the innovations in the large castle of Les Andelys in Normandy, in its famous castle Chateau-Gaillard. The king boasted that he could hold this castle even if its walls were made of butter. In fact, this castle fell just a few years after its construction, unable to withstand the onslaught of the French king, but, as in most such cases, the gates were opened to the winner by traitors inside the castle.

In that century, many old castles were expanded and completed; new towers, gatehouses, bastions and barbicans were erected; Completely new elements also appeared. The old wooden fences on the walls were gradually replaced by stone hinged loopholes. These loopholes essentially reproduced in stone the shape of old wooden fences - open galleries. Such hinged loopholes are a characteristic feature of 13th-century castles.

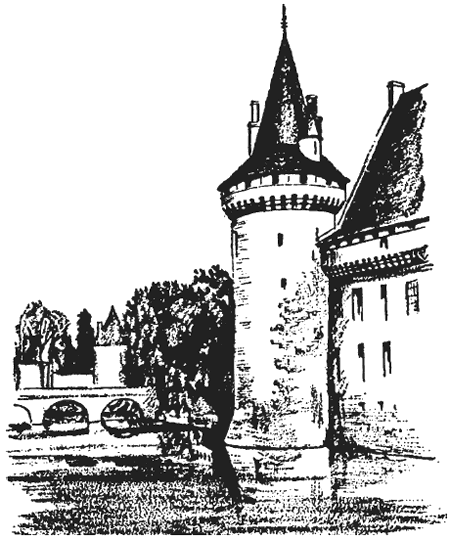

Rice. 18. One of the towers of the castle of Sully-sur-Loire; hinged loopholes are visible around the edge of the tower roof and along the upper edge of the wall. In this castle, the ancient roofs of the 14th century have been preserved unchanged to this day.

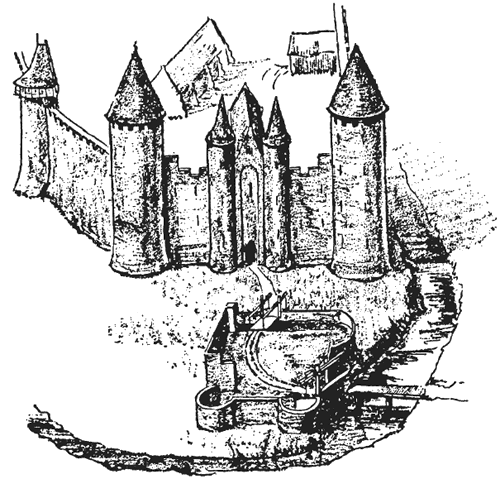

But at the end of this century, a completely new type of castle appeared in England, several of which were built in Wales. After Edward I seized power twice - in 1278 and 1282, this king, in order to retain what he had won, began to build new castles, just as King William I began to build for the same purpose two centuries earlier. But Edward’s buildings were strikingly different from their predecessors - castles built on bulk hills, surrounded by wooden palisades and earthen ramparts. In short, the new type of architecture lacked the main tower, but the walls and towers of the courtyard were significantly strengthened. At Conway and Caernarvon castles, the outer walls reached almost the same height as the previous main towers, and the flanking towers became simply prohibitively huge. Inside the walls were two more open courtyards, but they were smaller than the courtyards of the older, more extensive and open castles. Conway and Carnarvon were not built according to the correct plan, their architecture was adapted to the features of the terrain on which they were built, but the castles of Harlech and Beaumarie were built according to the same type of plan - these were quadrangular fortresses with very high strong walls and large cylindrical (drum) corners towers. In the castle courtyard there was another concentric wall with bastions. There is no space here to describe this type of castle architecture in detail, but at least the basic idea is now clear to you.

The same principle formed the basis for the construction of the last real castle in England - powerful high walls connecting the corner towers. At the end of the 14th century, new types of castles were built - such as Bodiam in Sussex, Nunney in Somerset, Bolton and Sheriff Hatton in Yorkshire, Lumley in Durgham and Queenborough on the Isle of Sheppey. The last castle was not quadrangular in plan, but round, with an internal concentric wall. This castle was razed to the ground by order of Parliament during Civil War in England, and not even a trace remains of him. About him appearance we know only from old drawings. The internal structure of these castles is not characterized by buildings scattered around the courtyard or attached to the walls; all rooms were built into the walls, they were turned into more orderly and comfortable places for work and living.

Rice. 19. It is shown how the hinged loopholes were constructed.

Later late XIV century, the architecture of the classic English castle falls into decay - the castle is replaced by a fortified manor house, for which home comfort and convenience are much more important than defense capability. Many castles built in the 15th century were quadrangular in plan, and most were surrounded by a moat; the only defensive structure left was the double tower covering the entrance. At the end of this century, the construction of such structures finally ceased, and the Englishman's castle turned into his ordinary home. In the 16th century, the great era of English estate building began.

This remark, of course, does not apply to continental castles; on the continent, socio-political conditions were completely different. This is especially true in Germany, where civil wars continued until the end of the 16th century, and castles were still in great demand. In England, the need for such fortified buildings remained only in the Welsh Alps and on the Scottish border. In the Welsh Alps, old castles were used for their intended purpose even in the 15th century; indeed, a completely new castle was built at this time near Raglan in Monmouthshire. It was very similar to the castles of Edward I, and was built around 1400 by Sir William of Thomas, known as the Blue Knight of Gwent, and his son Sir William Herbert, who later became Earl of Pembroke. One feature strikingly distinguished this castle from the castles of Edwardian times - a free-standing tower with a hexagonal plan, surrounded by its own moat and rampart with bastions. This is a separate castle located in front of the main castle. This building went down in history as the “yellow tower of Gwent”. This is a late example of new construction in a region where military clashes could be expected; on the northern borders, wars were fought almost constantly and without interruption. The raids of the Scots, who stole cattle, and the retaliatory punitive raids of the British did not stop. In such conditions, it was necessary to turn every estate, every village farm into a fortified castle. As a result, so-called saws, small quadrangular fortresses. Typically, such a fortress was a strong, dull, simple, but strong tower with a small courtyard, which was more like an ordinary village courtyard, and not at all a castle courtyard, surrounded by a high, flat, battlemented wall. Most of these saws were indeed ordinary farms, and when robbers appeared in the distance, the owner, his family and workers locked themselves in the tower, and herded the cattle into the yard. If the Scots took the trouble to besiege the fortress and break into the courtyard, then the people found refuge in the tower - they drove the cattle into the basement, and they themselves climbed to the top floor. But the Scots rarely engaged in sieges. They were always in a hurry to swoop in, grab everything that was in bad shape, and go home.

Rice. 20. Bird's eye view of Harleck Castle. This is one of the large castles built in the era of King Edward I. Characteristic The buildings are large, powerful cylindrical towers connected into a quadrangle by massive high walls. The entire castle thus became, to some extent, one large main tower, and the enlarged gate watchtower became the dominant part of the entire structure. In front of the main gate there is another tower, much smaller in size. There is also long bridge, spanning the moat, as well as a drawbridge (which has now, of course, been replaced by a stationary one). The drawbridge was located at a slight angle to the inner end of the approach road. The outer edge of the ditch is surrounded by a wall - a counter-scarp, and the other wall crowns the steep, rocky inner bank of the ditch. The castle is built on a high stone cliff, and the only place from which it could be attacked is exactly what is visible in the picture. One can imagine how difficult it was to overcome the counter-scarp, then the ditch, then climb the steep bank to the high walls, then - under continuous fire - break through the main wall and only after all approach even higher walls and towers. All residential and utility rooms of Garlek Castle were located behind the main gate, inside the castle.

The great era of castle construction almost completely coincides in time with the era of chivalry - from the 11th to the 15th centuries. Wars, even internecine and private ones, began to be distinguished by greater deceit and less courtliness, compared to the wars of earlier days, becoming the lot of hired professionals. The advent of cannons made even the strongest and most powerful castles vulnerable. It is curious, however, that two hundred years after the last castle was built in England, and many of them were abandoned and destroyed during the Civil War of 1642-1649, castles began to be used for their intended purpose again. Some of them withstood long sieges, fired from cannons that became much more powerful than those used in the 15th century, and not one of these castles was ever taken by storm.

Notes:

Counter-scarp is the slope of a ditch for long-term or temporary fortification.

When large landowners appeared in Europe, they began to build fortified estates for themselves. The house, outbuildings, barns and stables were surrounded by high wooden walls. A wide ditch was usually dug in front of them, into which water was diverted from a nearby reservoir. This is how the first castles appeared. But they were fragile, since the wood began to rot over time. Therefore, the walls and buildings had to be constantly updated. In addition, such buildings could easily be set on fire.

The first real ones knight's castles made of stone, which are well known in our time, began to be built at the end of the 9th and beginning of the 10th centuries. In total, 15 thousand such structures were built in Europe. They were especially fond of similar buildings in England. In these lands, a construction boom began during the time of William the Conqueror in the second half of the 11th century. The stone structures rose at a distance of 30 km from each other. This proximity was very convenient in case of attack. Cavalry detachments from other castles could quickly arrive at the defenders.

In the 10th-11th centuries, defensive stone structures consisted of a high multi-tiered tower. It was called donjon and was home to the knight and his family. It also housed food, servants, and armed guards. A prison was set up in which prisoners were kept. They dug a deep well in the basement. It was filled with groundwater. Therefore, the inhabitants of the donjon were not afraid of being left without water in the event of a long siege.

From the second half of the 11th century, the dungeons began to be surrounded by stone walls. Since that time, the defensive capabilities of the castle have increased significantly. The enemies first had to overcome high, strong walls, and then also take possession of a multi-tiered tower. And from it it was very convenient to pour hot tar on the heads of the invaders, shoot arrows and throw large stones.

The most active construction of reliable stone structures unfolded in 1150-1250. It was during these 100 years that it was built greatest number locks Kings and rich nobles built magnificent structures. Small nobles erected small but reliable stone fortresses.

At the beginning of the 13th century, towers began to be made not square, but round.. This design was more resistant against throwing machines and rams. In the 90s of the 13th century, one central tower was abandoned. Instead, they began to make many towers, and surrounded them with 2 or even 3 rows of walls. Much more attention was paid to strengthening the gates.

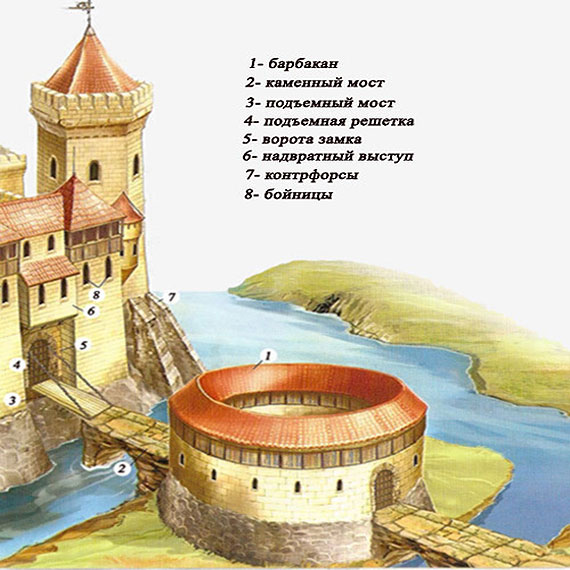

Previously, knightly castles were protected only by heavy doors and a rising bridge over a moat. Now a powerful metal grille has been installed behind the gate. She could go down and up, and was called gers. Its tactical advantage was that it could be used to shoot arrows at attackers through it. This innovation was supplemented barbican. It was a round tower located in front of the gate.

Therefore, the enemies first had to take possession of it, then overcome the drawbridge, break the metal grating of the castle, and only after that, overcoming the fierce resistance of the defenders, penetrate into the interior of the castle. And on top of the walls, the builders made stone galleries with special openings to the outside. Through them, the besieged fired bows and poured hot tar on their enemies.

Medieval knight's castle and its defensive elements

In these practically impregnable stone fortresses, everything was subject to maximum security. But they cared much less about internal comfort. There were few windows, and they were all narrow. Instead of glass, mica or the intestines of cows, bulls, and buffaloes were used. Therefore, even on a bright sunny day there was twilight in the rooms. There were a great many different staircases, corridors and passages. They created drafts. And this had a negative impact on the health of residents.

The rooms had fireplaces, and the smoke escaped through chimneys. But it was very difficult to heat rooms made of stone. Therefore, people have always suffered from lack of heat. The floors were also stone. They were covered with hay and straw on top. Furniture included wooden beds, benches, wardrobes, tables and chests. Hunting trophies in the form of stuffed animals and weapons hung on the walls. And this is how noble families lived with their servants and guards.

Attitudes towards comfort and convenience began to change in early XIV century. Knights' castles began to be built from brick. Accordingly, they became much warmer. Builders stopped making narrow window openings. They expanded significantly, and multi-colored glass replaced mica. The walls and floors were covered with carpets. Carved wooden furniture and porcelain dishes imported from the east appeared. That is, the fortresses turned into quite tolerable places to live.

At the same time, the locks retained such important functions as storage for products. They had basements and cellars. Grain, smoked meats, dried fruits and vegetables were stored in them. There were stocks of wine and fish in wooden barrels. Honey was stored in clay jugs filled with wax. Lard was salted in stone containers.

The halls and corridors were illuminated by oil lamps or torches. Candles made of wax or tallow were used in residential areas. A separate tower was intended for hay. It was kept for horses, of which there were a lot at that time. Each fortress had its own bakery. Bread was baked daily for the masters and their servants.

Ordinary people settled around these majestic buildings. In case of enemy attack, people hid behind strong walls. They also sheltered their livestock and property. Therefore, gradually, first villages and then small towns began to appear around the knights’ castles. Markets and fairs were held right under the walls. The owner of the fortress did not object to this at all, since such events promised him a good profit.

TO XVI century many knights' castles were completely surrounded by residential buildings. As a result of this, they lost their military defensive significance. At this time powerful artillery began to appear. It negated the importance of strong and high walls. And gradually the once impregnable fortresses turned only into places of residence for rich people. They were also used for prisons and warehouses. Nowadays, the former majestic buildings have become history and are of interest only to tourists and historians..

MAIN ELEMENTS OF A MEDIEVAL CASTLE

As mentioned above, medieval castles and each of their components were built according to certain rules. The following main structural elements of the castle can be distinguished:

Courtyard

Fortress wall

Let's look at them in more detail.

Most of the towers were erected on natural hills. If there were no such hills in the area, then the builders resorted to constructing a hill. As a rule, the height of the hill was 5 meters, but there were heights of more than 10 meters, although there were exceptions - for example, the height of the hill on which one of the Norfolk castles was placed near Thetford reached hundreds of feet (about 30 meters).

The shape of the castle territory varied - some were oblong, some were square, and there were courtyards in the shape of a figure eight. Variations were highly variable depending on the size of the host condition and site configuration.

After the site for construction was chosen, the first step was to dug it in with a ditch. The excavated earth was thrown onto the inner bank of the ditch, resulting in a rampart or embankment called a scarp. The opposite bank of the ditch was called, accordingly, the counter-scarp. If possible, a ditch was dug around a natural hill or other elevation. But, as a rule, the hill had to be filled in, which required a huge amount of earthwork.

The hill consisted of earth mixed with limestone, peat, gravel, brushwood, and the surface was covered with clay or wooden flooring.

The first fence of the castle was protected by all sorts of defensive structures designed to stop too rapid an attack by the enemy: hedges, slingshots (placed between pillars driven into the ground), earthen embankments, hedges, various protruding structures, for example, a traditional barbican that protected access to drawbridge. At the foot of the wall there was a ditch, they tried to make it as deep as possible (sometimes more than 10 m deep, as in Trematon and Lassa) and wider (10 m in Loches, 12 in Dourdan, 15 in Tremworth, 22 m - in Kusi). Typically, moats were dug around castles as part of a defensive system. They made it difficult to access the fortress walls, including siege weapons such as a battering ram or a siege tower. Sometimes the moat was even filled with water. In shape, it more often resembled the letter V than U. If a ditch was dug directly under the wall, a fence, a lower rampart, was erected above it to protect the patrol path outside the fortress. This piece of land was called a palisade.

An important property of a water-filled ditch is the prevention of undermining. Often rivers and other natural bodies of water were connected to ditches to fill them with water. The ditches needed to be periodically cleared of debris to prevent shallowing. Sometimes stakes were placed at the bottom of ditches, making it difficult to overcome by swimming. Access to the fortress was usually organized through drawbridges

Depending on the width of the ditch, it is supported by one or more supports. While the outer part of the bridge is fixed, the last section is movable. This is the so-called drawbridge. It is designed so that its plate can rotate around an axis fixed at the base of the gate, breaking the bridge and closing the gate. To set the drawbridge in motion, devices are used both on the gate itself and on its inside. The bridge is raised manually, using ropes or chains running through blocks in slots in the wall. To make work easier, counterweights can be used. The chain can go through blocks to the gate located in the room above the gate. This gate can be horizontal and rotated by a handle, or vertical and driven by horizontal beams threaded through it. Another way to lift the bridge is with a lever. Swinging beams are threaded through the slots in the wall, the outer end of which is connected by chains to the front end of the bridge plate, and counterweights are attached to the rear end inside the gate. This design facilitates rapid lifting of the bridge. Finally, the bridge plate can be designed according to the rocker principle.

The outer part of the plate, rotating around an axis at the base of the goal, closes the passage, and the inner part, on which the attackers may already be, goes down into the so-called. a wolf pit, invisible while the bridge is down. Such a bridge is called a tilting or swinging bridge.

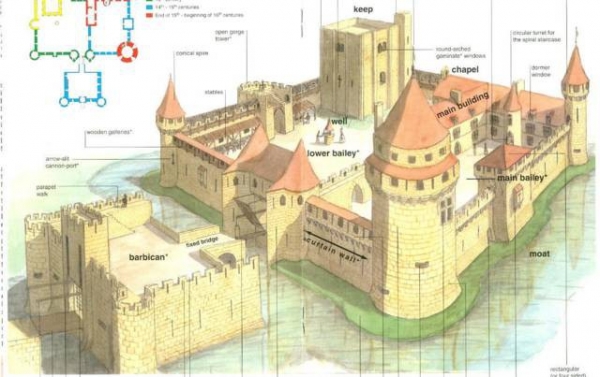

In Fig. 1. A diagram of the entrance to the castle is presented.

The fence itself consisted of thick solid walls - curtains - part of the fortress wall between two bastions and various side structures, collectively called

Fig.1. Castle entrance diagram

towers. The fortress wall rose directly above the moat, its bases went deep into the ground, and the bottom was made as flat as possible to prevent possible undermining by the attackers, as well as so that shells dropped from a height would ricochet off it. The shape of the fence depended on its location, but its perimeter was always significant.

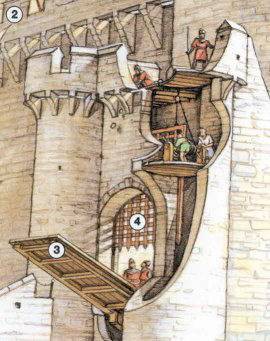

The fortified castle did not at all resemble an individual dwelling. The height of the curtains ranged from 6 to 10 m, thickness - from 1.5 to 3 m. However, in some fortresses, for example, in Chateau-Gaillard, the thickness of the walls in some places exceeds 4.5 m. Towers are usually round, less often square or polygonal , were built, as a rule, on the floor above the curtains. Their diameter (from 6 to 20 m) depended on the location: the most powerful were in the corners and near the entrance gates. The towers were built hollow, inside they were divided into floors by floors made of wooden planks with a hole in the center or on the side through which a rope passed, used to lift shells to the upper platform in case of defending the fortress. The stairs were hidden by partitions in the walls. Thus, each floor was a room where the soldiers were located; it was possible to light a fire in a fireplace built into the thickness of the wall. The only openings in the tower are the archery loopholes, long and narrow openings that widened into the room (Fig. 2).

Fig.2. Loophole - hole for archery

In France, for example, the height of such loopholes is usually 1 m, and the width is 30 cm on the outside and 1.3 m on the inside. Such a structure made it difficult for enemy arrows to penetrate, but the defenders had the opportunity to shoot in different directions.

The most important defensive element of the castle was the outer wall - high, thick, sometimes on an inclined base. Processed stones or bricks made up its outer surface. Inside it consisted of rubble stone and slaked lime. The walls were placed on a deep foundation, under which it was very difficult to dig.

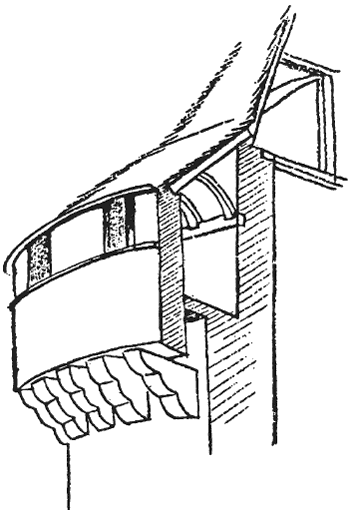

At the top of the fortress wall there was a so-called sentinel path, protected from the outside by a jagged parapet. It served for observation, communication between towers and defense of the fortress. A large wooden board was sometimes attached to the battlements between two embrasures, held on a horizontal axis, behind which crossbowmen took cover to load their weapons. During the wars, the patrol route was supplemented with something like a folding wooden gallery of the required shape, mounted in front of the parapet. Holes were made in the floor so that the defenders could shoot from above if the attackers took cover at the foot of the wall. Beginning with late XII centuries, especially in the southern regions of France, these wooden galleries, not very durable and easily flammable, began to be replaced with real stone ledges, built along with the parapet. These are the so-called machicolations, galleries with hinged loopholes (Fig. 3). They performed the same function as before, but their advantage was greater strength and the fact that they made it possible to throw cannonballs down, which then ricocheted off the gentle slope of the wall.

Fig.3. Tower with machicolations of the Marienberg fortress.

Sometimes several secret doors were made in the fortress wall for the passage of infantrymen, but only one large gate was always built, which was invariably fortified with special care, since it was on them that the main blow of the attackers fell.

The earliest way to protect a gate was to place it between two rectangular towers. A good example of this type of protection is the construction of gates in the 11th century Exeter Castle, which has survived to this day. In the 13th century, the square gate towers gave way to the main gate tower, which was a merger of the two previous ones with additional floors built above them. These are the gate towers of Richmond and Ludlow Castles. In the 12th century, the more common way to protect the gate was to build two towers on either side of the entrance to the castle, and only in the 13th century did gate towers appear in their completed form. The two flanking towers now join into one above the gate, becoming a massive and powerful fortification and one of the most important parts of the castle. The gate and entrance now turn into a long and narrow passage, blocked at each end with porticoes. These were doors that slid vertically along gutters carved in stone, made in the form of large gratings made of thick timber; the lower ends of the vertical beams were pointed and bound with iron, so the lower edge of the portico was a series of pointed iron stakes. These lattice gates were opened and closed using thick ropes and a winch located in a special chamber in the wall above the passage. Later, the entrance was protected with the help of "mertières", deadly holes drilled into the vaulted ceiling of the passage. Through these holes, objects and substances usual in such a situation - arrows, stones, boiling water and hot oil - rained down and poured on anyone who tried to force their way through to the gate. However, another explanation seems more plausible - water was poured through the holes if the enemy tried to set fire to the wooden gates, since the best way to penetrate the castle was to fill the passage with straw, logs, thoroughly soak the mixture with flammable oil and set it on fire; they killed two birds with one stone - they burned the lattice gates and fried the castle defenders in the gate rooms. In the walls of the passage there were small rooms equipped with rifle slits, through which the defenders of the castle could use their bows to shoot at close range the dense mass of attackers who were trying to break into the castle. In Fig.4. Various types of shooting slits are presented.

In the upper floors of the gate tower there were rooms for soldiers and often even living quarters. In special chambers there were gates, with the help of which the drawbridge was lowered and raised on chains. Since the gate was the place that was most often attacked by the enemy besieging the castle, they were sometimes provided with another means of additional protection - the so-called barbicans, which began at some distance from the gate. Typically, the barbican consisted of two high, thick walls running parallel outward from the gate, thus forcing the enemy to squeeze into the narrow passage between the walls, exposing himself to the arrows of the archers of the gate tower and the upper platform of the barbican hidden behind the battlements. Sometimes, to make access to the gate even more dangerous, the barbican was installed at an angle to it, which forced attackers to go to the gate on the right, and parts of the body not covered by shields became targets for archers. The entrance and exit of the Barbican were usually very intricately decorated.

Fig.4. Types of shooting slits.

Each more or less serious castle had at least two more rows of defensive structures (ditches, hedges, curtains, towers, parapets, gates and bridges), smaller in size, but built on the same principle. A fairly significant distance was left between them, so each castle looked like a small fortified city. Freteval can again be cited as an example. Its fences have a round shape, the diameter of the first is 140 m, the second is 70 m, the third is 30 m. The last fence, called the “shirt,” was erected very close to the donjon in order to block access to it.

The space between the first two fences constituted the lower courtyard. There was a real village there: the houses of peasants who worked on the master's fields, workshops and dwellings of artisans (blacksmiths, carpenters, masons, carvers, carriage makers), a threshing floor and stable, a bakery, a community mill and press, a well, a fountain, sometimes a pond with live fish, washroom, traders' counters. Such a village was a typical settlement of that time with chaotically located streets and houses. Later, such settlements began to go beyond the castle and settle in its surroundings on the other side of the moat. Their inhabitants, as well as the rest of the inhabitants of the seigneury, took refuge behind the fortress walls only in case of serious danger.

Between the second and third fences there was an upper courtyard with many buildings: a chapel, housing for soldiers, stables, kennels, dovecotes and a falcon yard, a pantry with food supplies, kitchens, and a pond.

Behind the “shirt,” that is, the last fence, stood the donjon. It was usually built not in the center of the castle, but in its most inaccessible part; it simultaneously served as both the dwelling of the feudal lord and the military center of the fortress. Donjon (French donjon) is the main tower of a medieval castle, one of the symbols of the European Middle Ages.

It was the most massive structure that was part of the castle buildings. The walls were gigantic in thickness and were installed on a powerful foundation capable of withstanding the blows of pickaxes, drills and battering guns of the besiegers.

It surpassed all other buildings in height, often exceeding 25 m: 27 m in Etampes, 28 m in Gisors, 30 m in Udun, Dourdan and Freteval, 31 m in Chateaudun, 35 m in Tonquedec, 40 in Losches, 45 m - in Provins. It could be square (Tower of London), rectangular (Loches), hexagonal (Tournoel Castle), octagonal (Gisors), four-lobed (Etampes), but more often round ones are found with a diameter of 15 to 20 m and a wall thickness of 3 to 4 m.

Flat buttresses, called pilasters, supported the walls along their entire length and at the corners; at each corner such a pilaster was crowned with a turret on top. The entrance was always located on the second floor, high above the ground. An external staircase led to the entrance, located at right angles to the door and covered by a bridge tower installed outside directly against the wall. For obvious reasons, the windows were very small. On the first floor there were none at all, on the second they were tiny and only on the next floors they became a little larger. These distinctive features - the bridge tower, the outer staircase and small windows - can be clearly seen at Rochester Castle and at Hedingham Castle in Essex.

The shapes of donjons are very diverse: in Great Britain, quadrangular towers were popular, but there were also round, octagonal, regular and irregular polygonal donjons, as well as combinations of several of these shapes. The change in the shape of the dungeons is associated with the development of architecture and siege technology. A tower that is round or polygonal in plan is better able to withstand the impact of projectiles. Sometimes when constructing a keep, builders followed the terrain of the area, for example by placing a tower on an irregularly shaped rock. This type towers appeared in the 11th century. in Europe, more precisely in Normandy (France). Initially it was a rectangular tower, adapted for defense, but at the same time being the residence of the feudal lord.

In the XII-XIII centuries. The feudal lord moved into the castle, and the donjon turned into a separate structure, significantly reduced in size, but stretched vertically. The tower was now located separately outside the perimeter of the fortress walls, in a place most inaccessible to the enemy, sometimes even separated by a ditch from the rest of the fortifications. It performed defensive and patrol functions (at the very top there was always a combat and patrol platform, covered with battlements). It was considered as the last refuge in defense from the enemy (for this purpose there were weapons and food warehouses inside), and only after the capture of the donjon was the castle considered conquered.

By the 16th century the active use of cannons turned the dungeons, towering above the rest of the buildings, into too convenient targets.

The donjon was divided inside into floors by wooden floors(Fig. 5).

Fig.5. Abenberg Castle tower (12th century) in section.

For defensive purposes, its only door was at the level of the second floor, that is, at a height of at least 5 m above the ground. One got inside via stairs, scaffolding or a bridge connected to a parapet. However, all these structures were very simple: after all, they had to be removed very quickly in the event of an attack. It was on the second floor that there was a large hall, sometimes with a vaulted ceiling, - the center of the lord's life. Here he dined, entertained, received guests and vassals, and even administered justice in winter. On the floor above were the rooms of the castle owner and his wife; They climbed there along a narrow stone staircase in the wall. On the fourth and fifth floors there are common rooms for children, servants and subjects. The guests also slept there. The top of the donjon resembled the top of a fortress wall with its crenellated parapet and sentinel path, as well as additional wooden or stone galleries. To this was added a watchtower to monitor the surrounding area.

The first floor, that is, the floor under the large hall, did not have a single opening leading out. However, it was neither a prison nor a stone bag, as archaeologists of the last century assumed. Usually there was a storeroom where firewood, wine, grain and weapons were stored.

In some dungeons, in the lower room, in addition, there was a well or an entrance to a dungeon dug under the castle and leading to an open field, which, however, was quite rare. By the way, the dungeon, as a rule, served to store food supplies for a year, and not at all to facilitate a secret escape, romantic or forced by R.I. Lapin. Article "Donjon". Encyclopedic Fund of Russia. Access address: http://www.russika.ru/.

The interior of the donjon is also of particular interest within the framework of the work.

DONJON INTERIOR

The interior of the lord's home can be characterized by three features: simplicity, modest decoration, and a small amount of furniture.

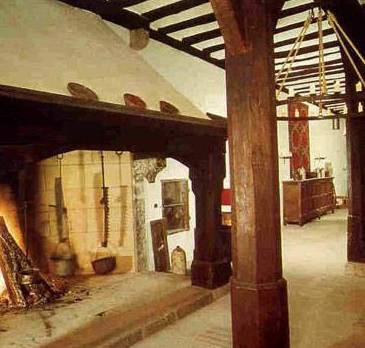

No matter how high the main hall was (from 7 to 12 meters) and spacious (from 50 to 150 meters), the hall always remained one room. Sometimes it was divided into several rooms by some kind of draperies, but always only for a while and due to certain circumstances. Trapezoidal window openings separated in this manner and deep niches in the wall served as small living rooms. Large windows, rather high than wide, with a semicircular top, were arranged in the thickness of the wall, similar to tower loopholes for archery.

No matter how high it was (from 7 to 12 meters) and spacious (from 50 to 150 meters), the hall always remained one room. Sometimes it was divided into several rooms by some kind of draperies, but always only for a while and due to certain circumstances. Trapezoidal window openings separated in this manner and deep niches in the wall served as small living rooms. Large windows, rather high than wide, with a semicircular top, were arranged in the thickness of the wall, similar to tower loopholes for archery. There was a stone bench in front of the windows, which was used for talking or looking out the window. Windows were rarely glazed (glass is an expensive material, used mainly for church stained glass windows); more often they were covered with a small lattice made of wicker rod or metal, or covered with glued fabric or an oiled sheet of parchment nailed to the frame.

A folding wooden sash was attached to the window, usually internal rather than external; Usually it was not closed unless one slept in the large hall.

Despite the fact that the windows were few and quite narrow, they still let in sufficient quantity light to illuminate the hall on summer days. In the evening or winter, sunlight was replaced not only by the fireplace fire, but also by tar torches, tallow candles or oil lamps, which were attached to the walls and ceiling. Thus, internal lighting always turned out to be a source of heat and smoke, but this was still not enough to overcome dampness - the real scourge of a medieval home. Wax candles, like glass, were intended only for the richest homes and churches.

The floor in the hall was made of wooden planks, clay or, less commonly, stone slabs, however, no matter what it was, it was never left uncovered. In winter it was covered with straw, either finely chopped or woven into rough mats. In spring and summer - reeds, branches and flowers (lilies, gladioli, irises). Fragrant herbs and fragrant plants, such as mint and verbena, were placed along the walls. Woolen carpets and bedspreads made from embroidered fabrics were generally used for seating only in bedrooms. In the large hall, everyone usually sat on the floor, laying down skins and furs.

The ceiling, which is also the floor of the upper floor, often remained untreated, but in the 13th century they began to try to decorate it with beams and caissons, creating geometric patterns, heraldic friezes or ornate patterns with images of animals. Sometimes the walls were painted in the same way, but more often they were simply painted in a specific color (preference was given to red and yellow ocher) or covered with a pattern that imitated the appearance of cut stone or a chessboard. Frescoes depicting allegorical and historical scenes, borrowed from legends, the Bible or literary works, are already appearing in princely houses. It is known, for example, that King Henry III of England loved to sleep in a room whose walls were decorated with episodes from the life of Alexander the Great, a hero who aroused special admiration in the Middle Ages. However, such luxury remained available only to the sovereign. An ordinary vassal, an inhabitant of a wooden dungeon, had to be content with a rough, bare wall, ennobled only by his own spear and shield.

Instead of wall paintings, tapestries with geometric, floral or historical motifs were used. However, more often these are not real tapestries (which were usually brought from the East), but mostly embroidery on thick fabric, like the so-called “Queen Matilda carpet” kept in Bayeux.

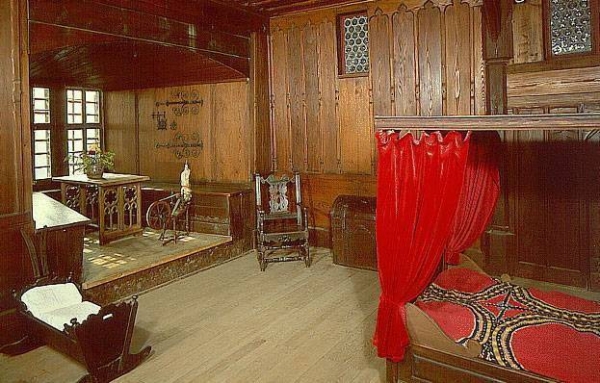

Tapestries made it possible to hide a door or window or to divide a large room into several rooms - “bedrooms”.

This word quite often did not mean the room where they slept, but the totality of all the tapestries, embroidered cloths and various fabrics intended for interior decoration. When going on a trip, tapestries were always taken with them, because they constituted the main element of decorating an aristocratic home, capable of giving it individuality.

In the 13th century, only wooden furniture existed. It was constantly moved (The word “furniture” comes from the word mobile (French) - movable. (Note per.)), since, with the exception of the bed, the rest of the furniture did not have a single purpose. Thus, the chest, the main type of furniture, served simultaneously as a wardrobe, table and seat. To perform the latter function, it could have a back and even handles. However, the chest is only an additional seat. Mostly they sat on common benches, sometimes divided into separate seats, on small wooden benches, on small stools without a back. The chair was intended for the owner of the house or an honored guest. Squires and women sat on armfuls of straw, sometimes covered with embroidered cloth, or simply on the floor, like servants and lackeys. Several boards placed on trestles made up a table; during meals it was placed in the center of the hall. It turned out to be long, narrow and somewhat taller than modern tables. The diners sat on one side, leaving the other free for serving dishes.

There was little furniture: besides chests, into which dishes, household utensils, clothes, money and letters were stuffed at random, sometimes there was a wardrobe or sideboard, less often - a sideboard, where the richest placed precious dishes or jewelry. Often such furniture was replaced by niches in the wall, hung with drapery or closed with doors. Clothes were usually not folded, but rolled and scented. Letters written on parchment were also rolled up before placing them in a linen bag, which served as a kind of safe, where, in addition, one or more leather wallets were kept.