About the difference in styles in the calendar

The difference in style arises from the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar.

The Julian calendar (“old style”) is the calendar adopted in Europe and Russia before the transition to the Gregorian calendar. Introduced into the Roman Republic by Julius Caesar on January 1, 45 BC, or 708 from the founding of Rome.

The Gregorian calendar was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582. The Pope removed 10 days from this year (from October 4 to 14), and also introduced a rule according to which, in the future, 3 days will be removed from every 400 years of the Julian calendar to align with the tropical year.

According to the Julian calendar, every 4th year (the number of which is divisible by 4) is a leap year, i.e. contains 366 days, not 365, as usual. This calendar lags behind the solar calendar by 1 day in 128 years, i.e. by about 3 days in 400 years. This lag was taken into account in the Gregorian calendar (" a new style"). For this purpose, "hundredths" (ending in 00) years are made not to be leap years, unless their number is divisible by 400.

1200, 1600, 2000 were leap years and will be 2400 and 2800, and 1300, 1400, 1500, 1700, 1800, 1900, 2100, 2200, 2300, 2500, 2600 and 2700 are normal. Each leap year ending in 00 increases the difference between the new and old styles by 1 day. Therefore, in the 18th century the difference was 11 days, in the 19th century - 12 days, but in the 20th and 20th centuries XXI centuries the difference is the same - 13 days, since 2000 was a leap year. it will increase only in the XXII century - to 14 days, then in the XXIII - to 15, etc.

A common date conversion from the old style to the new takes into account whether the year was a leap year and uses the next day difference.

Difference in days between “old” and “new” styles

| Century | Years according to the "old style" | Difference | |

| from March 1 | until February 29 | ||

| I | 1 | 100 | -2 |

| II | 100 | 200 | -1 |

| III | 200 | 300 | 0 |

| IV | 300 | 400 | 1 |

| V | 400 | 500 | 1 |

| VI | 500 | 600 | 2 |

| VII | 600 | 700 | 3 |

| VIII | 700 | 800 | 4 |

| IX | 800 | 900 | 4 |

| X | 900 | 1000 | 5 |

| XI | 1000 | 1100 | 6 |

| XII | 1100 | 1200 | 7 |

| XIII | 1200 | 1300 | 7 |

| XIV | 1300 | 1400 | 8 |

| XV | 1400 | 1500 | 9 |

| XVI | 1500 | 1600 | 10 |

| XVII | 1600 | 1700 | 10 |

| XVIII | 1700 | 1800 | 11 |

| XIX | 1800 | 1900 | 12 |

| XX | 1900 | 2000 | 13 |

| XXI | 2000 | 2100 | 13 |

| XXII | 2100 | 2200 | 14 |

Historical dates after the 3rd century AD are converted into modern chronology by adding to the date the difference characteristic of a given century. For example, the Battle of Kulikovo, according to chronicles, took place on September 8, 1380, in the 14th century. Therefore, according to the Gregorian calendar, her anniversary should be celebrated on September 8 + 8 days, that is, September 16.

But not all historians agree with this.

"An interesting thing is happening.

Let's take a current example: A.S. Pushkin was born on May 26, 1799 according to the old style. Adding 11 days for the 18th century, we get June 6 according to the new style. Such a day was then in Western Europe, for example, in Paris. However, let’s imagine that Pushkin himself celebrates his birthday among friends and already in the 19th century - then it is still May 26 in Russia, but already June 7 in Paris. Nowadays, May 26 of the old style corresponds to June 8 of the new one, however, Pushkin’s 200th anniversary was still celebrated on June 6, although Pushkin himself never celebrated it on this day.

The meaning of the error is clear: Russian history until 1918 lived according to the Julian calendar, therefore its anniversaries should be celebrated according to this calendar, thus being consistent with the church year. Even better connection historical dates And church calendar visible from another example: Peter I was born on the day of remembrance of St. Isaac of Dalmatia (from where St. Isaac's Cathedral in St. Petersburg comes). Consequently, even now we must celebrate his birthday on this holiday, which falls on May 30 of the old / June 12 of the new style. But if we translate Peter’s birthday according to the above rule, “what day was it in Paris then,” we get June 9, which, naturally, is erroneous.

The same thing happens with the famous holiday of all students - Tatiana's Day - the day of the founding of Moscow University. According to the church calendar, it falls on January 12 of the old style / January 25 of the new style, which is how we now celebrate it, while the erroneous rule, adding 11 days for the 18th century, would require it to be celebrated on January 23.

So, the correct celebration of anniversaries should take place according to the Julian calendar (i.e. today, to convert them to the new style, 13 days should be added, regardless of the century). In general, the Gregorian calendar in relation to Russian history, in our opinion, is completely unnecessary, just as double dating of events is not necessary, unless the events are immediately related to Russian and European history: For example, battle of Borodino It is legitimate to date August 26 according to the Russian calendar and September 7 according to the European calendar, and these are the dates that appear in the documents of the Russian and French armies."

Andrey Yurievich Andreev, Candidate of Historical Sciences, Candidate of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, Associate Professor of the Faculty of History of Moscow State University.

In Russia, the Gregorian calendar was introduced in 1918. The Orthodox Church continues to use the Julian calendar. Therefore, the easiest way is to translate the dates of church events. Just add 13 days and that’s it.

Our calendar uses the generally accepted style translation system (different increments of days in different centuries) where possible. If the source does not indicate by what style the date is celebrated, then the date is given according to this source without changes.

Holidays often seem like something immutable - it seems as if our parents, grandparents and more distant ancestors have always celebrated New Year about the same and then the same as today. Older people, on the contrary, are sure that winter holidays were celebrated “correctly” in their times, but now they have “spoiled.” However, in reality everything is not so simple. The schedule of holidays changes constantly - not only over the centuries, but also throughout the life of one generation.

So, 15 years ago, Russians would have been very surprised if they had learned that we did not go to work for almost a week after the New Year. 70 years ago they would not have believed that even January 1 could be a non-working day. And 120 years ago, they would have asked why take the New Year so seriously if there is Christmas, and how rest during the holidays can be prescribed by labor law, and not by church traditions.

We remembered how and when the New Year was celebrated throughout the history of our country, whether it has always been a time of rest for everyone, and also asked whether any changes in the “winter holiday” schedule await us in the near future.

Information about the calendar of the ancient Slavs is quite contradictory. According to some sources, the beginning of the year was considered the winter solstice (December 21-22 according to the current calendar), according to others - the spring equinox (March 20). Most likely, calendars differed in different Slavic tribes and localities. After Rus' adopted Christianity at the end of the 10th century, the Julian calendar began to be officially used, in which time was counted “from the creation of the world” (this event was believed to have occurred in 5508 BC).

It was assumed that the world was created on March 1, accordingly, this particular date was considered the day of the beginning of the next year. But in 1492 the king Ivan III approved the decision of the Moscow Council to postpone the New Year to September 1. This decision was made to comply with Byzantine traditions. In Byzantium, the beginning of the year was counted from September 1, since it was on this day in 312 that the first Christian emperor of Rome Konstantin defeated his rival, the last pagan emperor of Rome Maxentia.

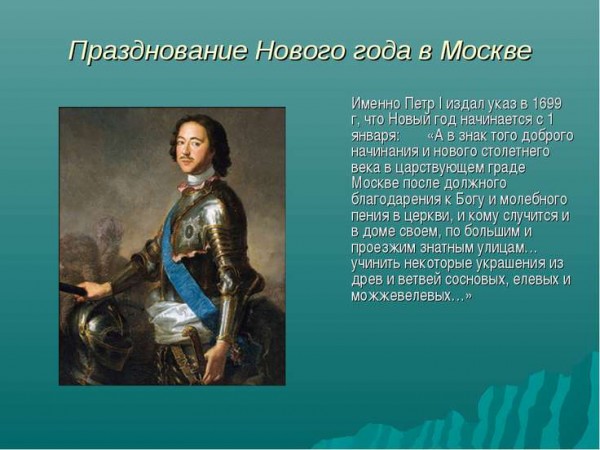

In 1699 (that is, in 7208 "from the creation of the world") future emperor, and at that time there was still a king Peter I issued a decree “On the writing henceforth of January from the 1st day of 1700 in all papers of the year from the Nativity of Christ, and not from the creation of the world.” Thanks to this, the Russian kingdom came closer to Western countries, where such chronology has been used since the 8th century. At the same time, Peter I did not introduce the Gregorian calendar, used in Catholic countries since 1582. The Russian Tsardom and then the Russian Empire continued to use the Julian calendar until the 20th century. Therefore, dates in Russia were 14 days behind Western ones.

It was believed that Jesus Christ was born on December 25, and the calendar was calculated “from his birth” - which means that the New Year should have been celebrated on this day. But for convenience, it was customary to count the beginning of the year from the nearest even date, January 1. On the initiative of Peter I, on this day in 1700, the New Year was celebrated on a national scale. Shortly after the issuance of the above-mentioned decree on the change of chronology, the king issued an additional decree dedicated to celebrations in honor of this event. On January 1, mass celebrations with fireworks (“fire fun”) were held on Red Square in Moscow. Residents of the capital were ordered on this day “to make some decorations from trees and branches of pine, spruce and juniper in front of the gates”, as well as “from small cannons, if anyone has them, and from several muskets, or other small guns, shoot three times and release several missiles."

However, later in Russia, as in other Christian countries, Christmas began to be considered a more important holiday. IN pre-revolutionary Russia this holiday was celebrated on December 25 according to the Julian calendar, that is, five days before the New Year. New Year's celebrations, therefore, were perceived only as an addition to the Christmas ones. The same thing happened in Catholic countries, where Christmas was celebrated (and still is celebrated) on December 25 according to the Gregorian calendar.

Ultimately, the idea of the birth of Jesus Christ merged in the minds of Russian people with archaic ideas about the birth of a young deity, symbolizing the onset of a new annual cycle. Many Slavic traditions have survived, becoming part of the Christmastide - the period from the Orthodox Christmas (December 25 according to the Julian calendar, January 7 according to the current Gregorian calendar) to the Epiphany (January 6 according to the Julian calendar, January 19 according to the Gregorian calendar). During this period, people practiced fortune telling, danced, and wore fancy dress. In many ways, this tradition is still alive.

As for non-working time and the New Year holidays, in pre-revolutionary times it was still impossible to talk about labor law in the version we are familiar with. Most The population of Russia consisted of peasants who were not hired workers. The landowners were interested in the results of their labor, not work time. Winter was a natural period of rest for peasants, so they did not have any difficulties with celebrating Christmas and Yuletide festivities - especially considering that church tradition directly prohibits work on Christian holidays.

The same applies to nobles, townspeople, merchants, artisans: they cannot be discussed in the categories of labor law; the relationship between employers and employees of those times is easier to describe in the categories military service(state and noble officials) or the patriarchal family (nobles and servants, artisans and apprentices).

Factory workers of the 19th century came more or less closer to the scheme of labor relations that we understand. It was during the settlement of relations between workers and factory owners that labor law began to emerge. However, it was too early to talk about guaranteed New Year or any other holidays. Even the length of the working day was not legally limited until 1897. Typically, workers worked 14-16 hours a day from Monday to Saturday. Theoretically, the factory owner could independently decide whether to allow them to rest on holidays. However, Christian traditions in the country were quite strong, so holidays on Christmas were, as a rule, allowed.

In 1897, the working day was limited for men to 11.5 hours (10 hours on Saturday), and for women and children - 10 hours on all working days, from Monday to Saturday (Law of June 2, 1897 "On the duration and distribution of work time in establishments of the factory industry"). As for holidays, the same law prohibited work on Sunday, Christmas, New Year and other “highly solemn holidays” (of which there were 14 a year). Moreover, on Christmas Eve, work had to end before noon. True, male workers could, by special agreement, work overtime, including on holidays, and many factory owners actively took advantage of this.

Almost immediately after October revolution Russia switched to the Gregorian calendar. January 26, 1918 Chairman of the Council people's commissars RSFSR Vladimir Lenin signed the decree "On the introduction of Russian Republic Western European calendar"According to the document, the next day after January 31, 1918 was prescribed to be counted not as February 1, but as February 14. The Russian Orthodox Church did not recognize this decision and still uses the Julian calendar. Therefore, Orthodox Christmas (December 25 according to the Julian calendar) began to be celebrated on 7 January However, the authorities no longer cared: after the revolution, the separation of church and state was announced.

As a result, great difficulties arose with the winter holidays. The celebration of Christmas was now contrary to the official atheist ideology. As for the New Year, after the change of the calendar it began to fall during the Nativity Fast. As you know, during the period of fasting, Christians must observe moderation in everything, that is, there can be no talk of any festivities. This created the preconditions for a clear division of society into two camps: someone continued to observe Christian traditions, celebrated Christmas and did not pay attention to the New Year - and someone accepted a new ideology, began to celebrate the New Year and not notice Christmas. Particularly persistent supporters of the Julian calendar continued to celebrate the so-called “old New Year,” which begins on January 14 in the Gregorian style. This tradition has taken root and has survived to this day - it is observed by many Russians, even those who have no idea about the calendar reform.

It is worth noting that the Soviet government also did not immediately reconcile with the New Year. Initially, all winter holiday traditions (such as decorating the Christmas tree) were attributed to Christmas. They were actively fought against as having a religious origin. Relevant slogans and poems were distributed in the media and on posters. Here is one of typical examples:

It'll be Christmas soon -

Ugly bourgeois holiday,

Connected from time immemorial

It's an ugly custom with him:

A capitalist will come to the forest,

Inert, true to prejudice,

He will cut down the Christmas tree with an axe,

Telling a cruel joke.

However, the traditions of a huge country cannot be broken in a short time. Especially when you consider that the Bolsheviks at that time had to solve much more important problems than the formation of an ideology regarding the winter holidays. Inevitably, confusion arose; in many places, Christmas continued to be celebrated quite officially. Vladimir Lenin himself sometimes visited Christmas trees for children, which, due to a misunderstanding, turned out to be reflected in the official chronicles. When the new government began to formulate labor legislation, Christmas, as one of the popular national holidays, was even declared a non-working day (Resolution of the Plenary Meeting of the Council of Trade Unions of January 2, 1919). However, already in 1929 this decision was canceled, and the celebration of Christmas was banned.

The official “rehabilitation” of the winter holiday tradition took place in 1935. In the issue dated December 28, the Pravda newspaper published a detailed letter from the First Secretary of the Kyiv Regional Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks) Pavel Postysheva, dedicated to justifying this tradition. Postyshev wrote: “In pre-revolutionary times, the bourgeoisie and bourgeois officials always arranged a Christmas tree for their children for the New Year. The children of the workers looked through the window with envy at the tree sparkling with multi-colored lights and the children of the rich having fun around it. Why do we have schools, orphanages, nurseries, children’s Are clubs and palaces of pioneers depriving the working children of the Soviet country of this wonderful pleasure?” As a result, the 1936 meeting was organized centrally throughout the country, and the advent of the next year, 1937, was celebrated with great pomp. In Moscow, two “main” Christmas trees were installed in Gorky Park and Manezhnaya Square, a Carnival Ball for excellent students was held at the House of Unions. The famous story was published in 1939 Arkady Gaidar"Chuk and Gek", ending with the joyful celebration of the New Year.

So the New Year became an official Soviet holiday. Naturally, no one remembered Christmas anymore at the state level. Old propaganda stories and pictures about Lenin on the Christmas tree were firmly associated with the New Year and only with it. Little by little, the holiday became overgrown with Soviet paraphernalia: the Christmas tree was decorated with a red star in combination with toys in the form of pioneers, tractor drivers and the “queen of the fields”, corn. At New Year's parties, children were told about the greatness of the USSR.

However, at the same time such archaic pagan characters as Father Frost and the Snow Maiden gained wide fame. Unlike the image of Jesus Christ, pagan myths were considered already extinct and therefore harmless for atheistic ideology. In 1953, at the Christmas tree in the House of Unions, Father Frost and the Snow Maiden sang:

Let's stand in a friendly circle around the Christmas tree

And we will sing with the whole country:

"Hail, our great Stalin!

Hail, our dear Stalin!"

It is worth noting that the first attempts to create the image of Father Frost, bringing gifts to children for the winter holidays, were made back in the 19th century. Having become familiar with Western traditions, Russians tried to come up with a character similar to Santa Claus (St. Nicholas) or “Grandfather Christmas.” However, this tradition did not take root well: the pagan spirit of winter and cold, Frost, was still predominantly an evil character. And only in Soviet years the kind Santa Claus has become a universally recognized symbol of the New Year.

December 31 and January 1 for a long time remained normal working days. New Year was considered primarily a children's holiday, so the authorities did not see the point in freeing adults from work. Only on December 23, 1947, the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR “On declaring January 1 a non-working day” was issued. It is curious that by the same decree, Victory Day on May 9 (considered a day off since 1945) was declared a working day. Some historians argue that in this way Joseph Stalin tried to downplay the significance of the Victory and “put in their place” veterans who, thanks to their life experience could pose a serious danger to the authorities. One way or another, May 9 was declared a day off again only in 1965, when the post of General Secretary of the CPSU Central Committee was held by Leonid Brezhnev(Decree of the Presidium of the USSR Supreme Council of April 25, 1965).

Moreover, January 1 in 1965 remained a non-working day. Over the past years, the attitude towards the New Year has changed: now it was not so much a time for matinees and Christmas trees for children's groups, but rather a family celebration. It was then that the late Soviet new year traditions, familiar to most modern Russians: champagne, Olivier salad, the song “A Christmas tree was born in the forest” (written by the poetess Raisa Kudasheva and composer Leonid Bekman in 1903-1905), the film “The Irony of Fate” (1975), postcards with Santa Claus and fairy-tale animals. Unlike May 1, May 9 and November 7, the New Year was little politicized. Although, of course, some attempts were made to link the national holiday with state ideology. In particular, since 1941, radio addresses of representatives of the supreme power to the people were occasionally voiced, and in 1971, Leonid Brezhnev introduced the tradition of New Year's televised addresses by the head of state, which is still alive today.

In general, the authorities did not try to change the family nature of the holiday. Soviet New Year's films, as a rule, were dedicated to love, friendship, informal industrial relations and other topics important to privacy, and not for the state. The holiday remained children's in the sense that even adults were allowed to be children at this time, fool around, play snowballs, build a snowman, and turn their attention not to “great achievements”, but to “philistine” worries like the festive table and gifts. It turns out that in the middle of the 20th century, adult citizens of the USSR did not “take away” the holiday from children, but joined it.

From 1947 until the collapse of the USSR in 1991, only January 1 was invariably a non-working day. In 1993, January 2 was also declared a holiday (RSFSR Law of September 25, 1992 ""). At the same time, January 7 became a day off. Despite the fact that on December 12, 1993, it was adopted that consolidated the secular nature of the state, the new Russian government recognized Christmas as an official holiday. In this way, she paid tribute to the fashion for the revival of Christian traditions, and also showed solidarity with Western countries, where Christmas was still considered a more important holiday than the New Year. It is curious that November 7 (which continued to be called the Day of the Great October Revolution) retained its holiday status. socialist revolution). While reviving pre-revolutionary traditions, the authorities have not yet decided to abandon communist traditions.

The same regulatory act fixed the transfer holidays: Now, if a holiday fell on a Saturday or Sunday, the following Monday was considered a non-working day. Thanks to this, Russians were no longer upset if a holiday coincided with a weekend: the number of non-working days compared to a regular week still increased.

In the 1980-1990s, New Year traditions began to penetrate into Russia. foreign countries. Firstly, the whole country became famous for the American Santa Claus in a sleigh with reindeer, emerging from the fireplace to the sounds of the Jingle Bells song and putting gifts in stockings. Secondly, it has become fashionable to associate each year with one or another animal, as is customary in China (although the Chinese themselves celebrate the New Year later, in January-February - a new date is set every year). In the early 1990s, an old Father Frost made of papier-mâché or plastic and Soviet comedies were signs of a “wrong” New Year, and a bright new Santa, Hollywood films and honoring the animal symbol were attributes of a successful holiday.

But over time, as anti-American sentiment grew, Santa Claus regained his position. In the 2000s, Santa Claus gradually began to turn into almost a negative character. Now many Russians consider it a symbol of a “consumerist and soulless” holiday, and true fun is symbolized by Father Frost. At the same time, Chinese animals retained their positions. Starting in November, Russians begin to wonder who will patronize them next year - a horse, a sheep, a monkey or another of the 12 animals?

For the first time after the collapse of the USSR, supporters of the revival of pre-revolutionary traditions hoped that the celebration of the New Year would lose popularity, and Christmas would again take its place. They pointed out that Orthodox Christmas is still celebrated according to the Julian calendar, which means that January 1 falls during the period of Lent. However, it was not possible to change the main winter holiday. Most Russians now widely celebrate the New Year, but only religious people seriously celebrate Christmas. Only certain elements of the Christian holiday have been revived in popular culture - for example, Christmas tree angel toys and indoor decorations in the form of a manger with the baby Jesus. Of the religious celebrations, Easter has gained more popularity than Christmas. Even the expression “Easter Christian” has appeared - a person who calls himself a believer, but attends church only once a year on this holiday.

Serious changes to the list of official holidays were made by Federal Law of December 29, 2004 No. 201-FZ "". Firstly, the New Year was now prescribed to be celebrated for five whole days, from January 1 to January 5. Christmas also remained a non-working day, that is, in fact, January 6 was the only working day in the week-long series of winter holidays. Secondly, instead of November 7, November 4 was declared non-working, which was ordered to be considered “Day of national unity". May 2 became a working day (before that, in honor of Spring and Labor Day, two days were non-working: May 1 and 2). Also, December 12 was declared a working day. Constitution Day.

In 2012, the New Year holiday schedule changed again (). From now on, the holiday lasts from January 1 to January 8. However, in reality this does not mean an extension, but a reduction in the holidays. The fact is that at the same time it was decided to postpone the weekends coinciding with the New Year holidays, not to the next working day, but to join them with any of the other holidays at the discretion of the Government of the Russian Federation. Now, due to the “extra” New Year’s weekend, the May holidays are lengthening.

This decision was made due to the fact that the too long New Year holidays caused dissatisfaction among a considerable part of the population. Someone claimed that his loved ones drank too much alcohol in 10 days. Someone complained about the cancellation of the May 2nd holiday. Previously, taking into account the postponement of weekends, the May holidays became a fairly long rest period, and summer residents used it for sowing work. Now, the owners of the gardens argued, the holidays were taken away from them and given to those who like to “just laze around” on New Year’s Day. It was also suggested that the new holiday schedule is designed for those who can fly away to warm countries in winter. At the same time, low-income citizens lost the opportunity to bask in the May sun for an extra couple of days.

The new edition of the Labor Code of the Russian Federation was supposed to satisfy both New Year lovers and supporters May holidays. The winter holidays have hardly decreased, but the spring holidays have increased by a couple of days.

However, the voices of dissatisfaction are still not silent. Some citizens think that the long New Year holidays are, in principle, too great a luxury. And in general, Russians, in their opinion, rest too much. At the beginning of December 2014, the State Council of the Republic of Tatarstan introduced a bill to the State Duma canceling the transfer of holidays that coincided with weekends. The authors of the document indicate that over the years 1992-2014, the number of non-working holidays increased from nine to 14. Taking into account transfers, their number increases to almost two dozen per year. The State Council of Tatarstan believes that this has a negative impact on production and the economy.

Critics of this position claim that where work cannot be objectively interrupted, it is not interrupted. Shops do not close, continuous cycle enterprises do not stop, entrepreneurs do not postpone important meetings and negotiations, paid clinics and service establishments continue to operate. For many companies involved in the entertainment and tourism industry, winter holidays, on the contrary, are an emergency period.

In fact, the only area where vacations actually usually last more than a week without any reservations is government agencies (not counting emergency services). If a Russian needs to obtain any certificate at the beginning of January, he may face great difficulties. According to critics, it is necessary to develop a bill that would oblige officials to organize shifts on holidays (and possibly on regular weekends: after all, it is difficult for most Russians to take time off from work to visit a government agency). At the same time, you should not take away the holidays from ordinary citizens, who cannot always count on proper rest.

Another fresh bill introduced to the State Duma in November by a group of deputies raises another popular topic. Many citizens are unhappy that December 31 is a working day. After all, traditionally this date is associated with the New Year. It is on this day that it is customary to gather a table, invite guests, communicate and have fun until the morning. For many, January 1 is no longer a holiday, but a rest after the holiday. Russians complain that on December 31 they have to get up early in the morning (although they would like to get some sleep before a sleepless night), go to work (although no one there thinks about the work process), come home in the evening and frantically, hastily prepare to receive guests. The deputies proposed to include December 31 as a non-working day, and make January 8 a working day. Thus, the holidays will not be lengthened, but simply shifted.

Whatever initiatives are developed, the holiday schedule for 2015 has already been approved (Resolution of the Government of the Russian Federation of August 27, 2014 No. 860 ""). Non-working days January 3 and 4 (Saturday and Sunday) will be moved to January 9 and May 4. As a result, Russians will have a holiday from January 1 to 11, from May 1 to 4, and from May 9 to 11. Also closed will be February 21-23, March 7-9, June 12-14 and November 4, which falls on Wednesday.

There are less than two weeks left before the start of the all-Russian “winter holidays”. Probably, on New Year's Eve it would be best to forget about the background of the holiday and about possible future changes, and just have a good rest. In the end, the main thing never changes: the year begins anew, as if from scratch.

Since by this time the difference between the old and new styles was 13 days, the decree ordered that after January 31, 1918, not February 1, but February 14. The same decree prescribed, until July 1, 1918, after the date of each day according to the new style, to write in brackets the number according to the old style: February 14 (1), February 15 (2), etc.

From the history of chronology in Russia.

The ancient Slavs, like many other peoples, initially based their calendar on the period of changing lunar phases. But already by the time of the adoption of Christianity, i.e. by the end of the 10th century. n. e., Ancient Rus' I used the lunisolar calendar.

Calendar of the ancient Slavs. It was not possible to definitively establish what the calendar of the ancient Slavs was. It is only known that initially time was counted by seasons. Probably, the 12-month lunar calendar was also used at the same time. In later times, the Slavs switched to a lunisolar calendar, in which an additional 13th month was inserted seven times every 19 years.

The most ancient monuments of Russian writing show that the months had purely Slavic names, the origin of which was closely related to natural phenomena. Moreover, the same months, depending on the climate of the places in which different tribes lived, received different names. So, January was called where the section (the time of deforestation), where the prosinets (after the winter clouds the blue sky appeared), where the jelly (since it became icy, cold), etc.; February—cut, snowy or severe (severe frosts); March - berezozol (there are several interpretations here: the birch begins to bloom; they took sap from birches; they burned the birch for coal), dry (the poorest in precipitation in the ancient Kievan Rus, in some places the earth was already dry, the sap (a reminder of birch sap); April - pollen (blooming of gardens), birch (beginning of birch flowering), duben, kviten, etc.; May - grass (grass turns green), summer, pollen; June - Cherven (cherries turn red), Izok (grasshoppers chirp - “Izoki”), Mlechen; July - lipets (linden blossoms), cherven (in the north, where phenological phenomena are delayed), serpen (from the word “sickle”, indicating the time of harvest); August - sickle, stubble, roar (from the verb “to roar” - the roar of deer, or from the word “glow” - cold dawns, and possibly from “pasori” - aurora); September - veresen (heather blossoms); ruen (from the Slavic root word meaning tree, giving yellow paint); October - leaf fall, “pazdernik” or “kastrychnik” (pazdernik - hemp buds, the name for the south of Russia); November - gruden (from the word “heap” - frozen rut on the road), leaf fall (in the south of Russia); December - jelly, chest, prosinets.

The year began on March 1, and around this time agricultural work began.

Many ancient names of months later moved into the series Slavic languages and largely held in some modern languages, in particular in Ukrainian, Belarusian and Polish.

![]()

At the end of the 10th century. Ancient Rus' adopted Christianity. At the same time, the calendar used by the Romans came to us - the Julian calendar (based on solar year), with Roman names of months and a seven-day week. It counted years from the “creation of the world,” which allegedly occurred 5508 years before our chronology. This date - one of the many variants of eras from the “creation of the world” - was adopted in the 7th century. in Greece and has been used by the Orthodox Church for a long time.

For many centuries, the beginning of the year was considered March 1, but in 1492, in accordance with church tradition, the beginning of the year was officially moved to September 1 and was celebrated this way for more than two hundred years. However, a few months after Muscovites celebrated their next New Year on September 1, 7208, they had to repeat the celebration. This happened because on December 19, 7208, a personal decree of Peter I was signed and promulgated on the reform of the calendar in Russia, according to which a new beginning of the year was introduced - from January 1 and a new era - the Christian chronology (from the “Nativity of Christ”).

Peter's decree was called: "On the writing henceforth of Genvar from the 1st day of 1700 in all papers of the year from the Nativity of Christ, and not from the creation of the world." Therefore, the decree prescribed that the day after December 31, 7208 from the “creation of the world” should be considered January 1, 1700 from the “Nativity of Christ.” In order for the reform to be adopted without complications, the decree ended with a prudent clause: “And if anyone wants to write both those years, from the creation of the world and from the Nativity of Christ, freely in a row.”

Celebrating the first civil New Year in Moscow. The day after the announcement of Peter I’s decree on calendar reform on Red Square in Moscow, i.e. December 20, 7208, a new decree of the tsar was announced - “On the celebration of the New Year.” Considering that January 1, 1700 is not only the beginning of a new year, but also the beginning of a new century (Here a significant mistake was made in the decree: 1700 is last year XVII century, and not the first year of the XVIII century. The new century began on January 1, 1701. An error that is sometimes repeated today, the decree ordered that this event be celebrated with especially solemnity. It gave detailed instructions on how to organize a holiday in Moscow. On New Year's Eve, Peter I himself lit the first rocket on Red Square, giving the signal for the opening of the holiday. The streets were illuminated. The ringing of bells and cannon fire began, and the sounds of trumpets and timpani were heard. The Tsar congratulated the population of the capital on the New Year, and the festivities continued all night. Multi-colored rockets took off from the courtyards into the dark winter sky, and “along the large streets, where there is space,” lights burned—bonfires and tar barrels attached to poles.

The houses of the residents of the wooden capital were decorated with needles “from trees and branches of pine, spruce and juniper.” For a whole week the houses were decorated, and as night fell the lights were lit. Shooting “from small cannons and from muskets or other small weapons,” as well as launching “missiles,” were entrusted to people “who do not count gold.” And “poor people” were asked to “put at least a tree or branch on each of their gates or over their temple.” Since that time, our country has established the custom of celebrating New Year's Day on January 1 every year.

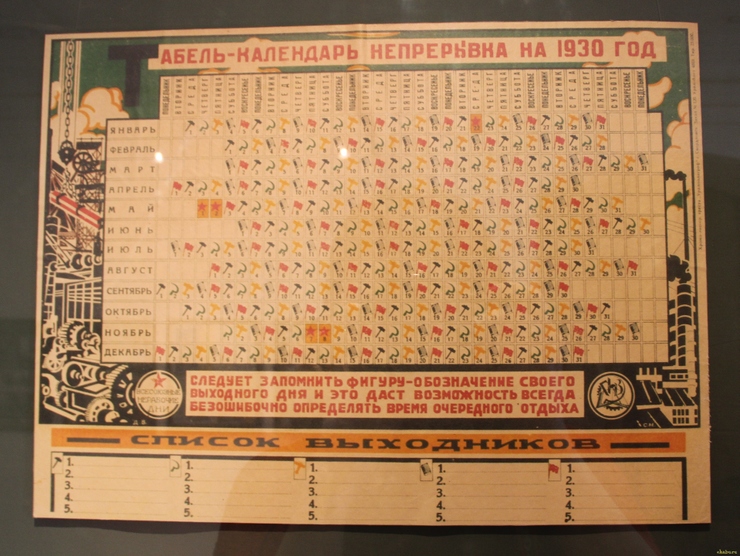

After 1918, there were still calendar reforms in the USSR. In the period from 1929 to 1940, calendar reforms were carried out in our country three times, caused by production needs. Thus, on August 26, 1929, the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR adopted a resolution “On the transition to continuous production in enterprises and institutions of the USSR,” which recognized the need to begin a systematic and consistent transfer of enterprises and institutions to continuous production starting from the 1929-1930 business year. In the fall of 1929, a gradual transition to “continuity” began, which ended in the spring of 1930 after the publication of a resolution of a special government commission under the Council of Labor and Defense. This decree introduced a unified production timesheet and calendar. The calendar year had 360 days, i.e. 72 five-day periods. It was decided to consider the remaining 5 days as holidays. Unlike the ancient Egyptian calendar, they were not located all together at the end of the year, but were timed to coincide with the Soviet memorable days and revolutionary holidays: January 22, May 1 and 2, and November 7 and 8.

The workers of each enterprise and institution were divided into 5 groups, and each group was given a day of rest on every five-day week for the whole year. This meant that after four working days there was a day of rest. After the introduction of the “uninterrupted” period, there was no longer a need for a seven-day week, since weekends could fall not only on different days of the month, but also on different days of the week.

However, this calendar did not last long. Already on November 21, 1931, the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR adopted a resolution “On the intermittent production week in institutions,” which allowed the People's Commissariats and other institutions to switch to a six-day intermittent production week. For them, permanent days off were established on the following dates of the month: 6, 12, 18, 24 and 30. At the end of February, the day off fell on the last day of the month or was postponed to March 1. In those months that contained 31 days, the last day of the month was considered the same month and was paid specially. The decree on the transition to an intermittent six-day week came into force on December 1, 1931.

Both the five-day and six-day periods completely disrupted the traditional seven-day week with a general day off on Sunday. The six-day week was used for about nine years. Only June 26, 1940 Presidium Supreme Council The USSR issued a decree “On the transition to an eight-hour working day, to a seven-day working week and on the prohibition of unauthorized departure of workers and employees from enterprises and institutions,” In development of this decree, on June 27, 1940, the Council of People’s Commissars of the USSR adopted a resolution in which it established that “in excess Sundays non-working days are also:

January 22, May 1 and 2, November 7 and 8, December 5. The same decree abolished the six special days of rest and non-working days that existed in rural areas on March 12 (Day of the Overthrow of the Autocracy) and March 18 (Paris Commune Day).

On March 7, 1967, the Central Committee of the CPSU, the Council of Ministers of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Council of Trade Unions adopted a resolution “On the transfer of workers and employees of enterprises, institutions and organizations to a five-day work week with two days off,” but this reform did not in any way affect the structure of the modern calendar."

But the most interesting thing is that passions do not subside. The next revolution is happening in our new time. Sergey Baburin, Victor Alksnis, Irina Savelyeva and Alexander Fomenko contributed to State Duma a bill on the transition of Russia from January 1, 2008 to the Julian calendar. In the explanatory note, the deputies noted that “there is no world calendar” and proposed establishing a transition period from December 31, 2007, when, for 13 days, chronology would be carried out simultaneously according to two calendars at once. Only four deputies took part in the voting. Three are against, one is for. There were no abstentions. The rest of the elected representatives ignored the vote.

On January 24 (February 6), 1918, the Council of People's Commissars, “in order to establish in Russia the same calculation of time with almost all cultural peoples,” adopted a decree “On the introduction of the Western European calendar in the Russian Republic.”

In pre-revolutionary Russia, chronology was carried out on the basis of the Julian calendar, adopted under Julius Caesar in 45 BC. e. and was in effect in all Christian countries until October 1582, when the transition to the Gregorian calendar began in Europe. The latter turned out to be more attractive from an astronomical point of view, since its discrepancy with the tropical year of one day accumulates not over 128 years, as in the Julian, but over 3200 years.

The issue of introducing the Gregorian calendar in Russia has been discussed several times, starting from the 30s of the 19th century. Since the Julian calendar is based on the Easter circle, and the Gregorian calendar is tied to the astronomical day of the vernal equinox, domestic experts each time preferred the first, as the most consistent with the interests of the Christian state. But in official documents related to international activities, and also in some periodicals it was customary to indicate the date according to two traditions at once.

After the October Revolution, the Soviet government took a number of measures aimed at separating church and state and secularizing the life of society. Therefore, when deciding on the transition to a new calendar system, the interests of the church were no longer taken into account; state expediency came to the fore.

Since by the time the decree was adopted the difference between the Julian and Gregorian calendars was 13 days, it was decided that after January 31, 1918, not February 1, but February 14, should be counted.

Until July 1, 1918, the decree prescribed that after the number in the new (Gregorian) style, the number in the old (Julian) style should be indicated in brackets. Subsequently, this practice was preserved, but they began to place the date in brackets according to the new style.

When recalculating dates from the old to the new style, 10 days are added to the number according to the old style if the event occurred in the period from October 5, 1582 to February 29, 1700, 11 days for the period from March 1, 1700 to February 29, 1800 , 12 days for the period from March 1, 1800 to February 29, 1900, 13 days for the period from March 1, 1900 to February 29, 2100, etc.

According to established tradition, events that occurred before the advent of the Gregorian calendar in 1582 are usually dated according to the Julian calendar, although they can also be recalculated taking into account the increasing difference over the centuries.

Lit.: Decree on introductionWestern Europeancalendar // Decrees Soviet power. T. 1. M., 1957; The same [Electronic resource]. URL:

The October Revolution of 1917 and the seizure of power by the Bolsheviks influenced all aspects of the public life of the former Russian Empire. The foundations of Russian society were mercilessly broken, banks were nationalized, landowners' lands were confiscated, the church was separated from the state. The problems of keeping track of time did not go unnoticed. Calendar reform has been brewing for a long time, since mid-19th century. In pre-revolutionary Russia, the Julian calendar was used in civil and church life, and in most Western countries - the Gregorian calendar. Domestic scientists P. M. Saladilov, N. V. Stepanov, D. I. Mendeleev have repeatedly proposed various options for changing the chronology system. The objective of the reform was to eliminate the 12-day and then 13-day difference that arose due to different ways Leap year calculations. These proposals encountered a negative reaction from the Russian Orthodox Church and a number of senior officials who defended the opinion that the introduction of a new calendar would be a betrayal of the canons of Orthodoxy.

The Bolsheviks raised the issue of calendar reform already in November 1917. In less than two months, the projects were prepared, and on January 24, 1918, the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, Lenin, signed the decree “On the introduction of the Western European calendar in the Russian Republic”1. The document ordered the introduction of the Gregorian calendar into civil use instead of the existing Julian calendar in order to establish the same chronology system with the majority of world powers. To equalize the daily count, after January 31, 1918, it was necessary to count not the 1st, but the 14th of February.

The change in the chronology style caused a negative reaction from the Church. At the Local Council held in 1917-1918, the introduction of the Gregorian calendar became the subject of heated discussion2. It was decided to consider the issue of adopting a new calendar at a general meeting of two departments - on worship and the legal status of the Church in the state. It took place on January 29, 1918. The presiding Metropolitan Arseny (A.G. Stadnitsky) demanded a speedy solution to the problem - by the next day. In his opinion, both departments should have developed a reasoned position on such a fundamental issue for the Church. The urgency was dictated by the introduction of the new style two days later, on February 1st.

At the meeting they unanimously decided to preserve the Julian style of chronology in church use. One of the council delegates, professor of theology at the Moscow Theological Academy S.S. Glagolev, was instructed to prepare a project on the calendar issue, which he announced at the council meeting on January 303. It stated that:

1) the introduction of a new style in civil life should not prevent believers from adhering to the Julian calendar; 2) The Church must preserve the old style, because the introduction of a new calendar into church use would entail the elimination of the Feast of the Presentation in 1918; 3) the issue of changing the style should be the subject of discussion and be decided by an Ecumenical Council with the participation of all Christians; 4) the rules on celebrating Easter cannot be applied to the Gregorian calendar, since in some years, according to the new style, it was celebrated earlier than the Jewish Passover; 5) it was emphasized that a new, corrected calendar is necessary for everything Christendom, but the significance of the Gregorian calendar in this capacity was denied.

Glagolev's position expressed the official point of view of the Orthodox Church. According to the decision of one of the first Ecumenical Councils in Nicaea, it was established that the Christian Easter should be celebrated later than the Jewish one. The Russian Orthodox Church has consistently followed this rule for many years and has repeatedly accused Catholic Church in violation of it. However, due to the change political situation in the country the Church was forced to soften its tough position. In 1918, the possibility of carrying out a calendar and closely related Easter reform was not denied. At the same time, the possibility of holding it was directly made dependent on the convening of the Ecumenical Council and, therefore, was postponed indefinitely. According to Glagolev, before this, secular authorities had no right to prevent believers from using the Julian calendar for internal calculations. This statement was directly related to the negative attitude of the leadership of the Orthodox Church towards interference in its affairs by the Soviet government. After a brief discussion, the conclusion was approved by the Council4.

Soon for in-depth study On the calendar issue, a special commission was formed5. It included delegates of the Council of the Russian Orthodox Church, Bishop Pachomius of Chernigov (P. P. Kedrov), professors S. S. Glagolev, I. I. Sokolov, I. A. Karabinov, B. A. Turaev, P. N. Zhukovich . Glagolev and Sokolov agreed that the Gregorian calendar is harmful, and the Julian calendar meets scientific requirements. However, this did not mean that it was necessary to preserve the old style in Russia. In particular, Glagolev proposed canceling the 31st

months, then in two years the old style would coincide with the new6. They also proposed another option for correcting the Gregorian calendar - through the abolition of one day of any 31st day and the elimination of one leap year every 128 years. At the same time, it was recognized that such a change could only be made by decision international conference. The researcher admitted that it would be more correct to move the old style by the indicated method not by 13, but by 14 days. From his point of view, the astronomical calculations he carried out proved that this project was more accurate. However, despite such radical proposals, the scientist believed that in the near future the Church should preserve the old style7.

The members of the commission adopted a resolution which noted the impossibility independent decision ROC on the issue of introducing the Gregorian calendar. Patriarch Tikhon was asked to draw up a special letter addressed to the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople in order to clarify the points of view on the calendar problem of all autocephalous Orthodox churches.

Due to the outbreak of the Civil War, meetings of the commission were no longer held. Its activities were limited to the compilation and attempt to publish the church calendar for 19198.

In subsequent years, the Russian Orthodox Church continued to adhere to the old style. One of the reasons for this was the negative attitude of the clergy towards the Soviet regime. A noteworthy statement was made by one of the delegates of the Local Council, M. A. Semyonov: “I would believe that one should not pay any attention to the decrees of the Bolsheviks and not react to them in any way. I know that many people do this.”9

In the first months of Soviet power, the church did not consider it possible to recognize its legitimacy. This state of affairs could not suit the leadership of the Bolshevik Party. After the final victory in Civil War it begins a policy of terror against individual clergy and the Church as a whole. For its final subordination to the OGPU, a renovationist movement was organized and a special anti-religious commission was created. Not the least role in this process was played by the fact of recognition of the Gregorian calendar. In the wake of persecution, Patriarch Tikhon was forced to sign documents that ordered that the day following October 1, 1923 be counted as October 1410. At the same time, it was pointed out that the introduction of the new calendar does not affect the dogmas and sacred canons of the Orthodox Church and is in strict accordance with the data of astronomical science. It was especially emphasized that the decree was not the introduction of the Gregorian calendar, but only a correction of the old Easter11. This decision was made under pressure from the OGPU. However, the dissatisfaction of many believers and ministers of the Church prompted the Patriarch to reverse his decision on November 8, citing the fact that “the convenient time for switching to a new style has already passed”12.

The reaction of the authorities followed immediately: the office of the patriarch was sealed, copies of the message were confiscated, and the texts of the previous decree were posted on the streets of Moscow without permission. Tikhon made an official statement to the USSR Central Executive Committee, in which he admitted that reform “is possible in a natural and painless form.” The Patriarch opposed the interference of civil authorities in its implementation, “because outside interference does not bring it closer, but distances it, does not facilitate, but complicates its implementation”13. The main reasons for reluctance and opposition to the introduction of a new style were formulated. As Tikhon argued, the Russian people were distinguished by their conservatism towards change. The slightest changes lead to confusion. The church year is closely connected with folk life and economic year peasant, since holidays determine the beginning of field work. The calendar reform was compromised by the renovationist movement because they refused to observe many church canons."

The Soviet government, despite all its efforts, failed to force the Church to change its calendar. The result was a duality that formed additional problems in determining church holidays.

This situation remained until the end of the 1920s. Having established himself in power, Stalin proclaimed a course towards the industrialization of the USSR. According to the country's leadership, the new calendar had to correspond to the production cycle.

Another important requirement was its “deliverance” from a religious basis. In particular, it was supposed to change the era of chronology, replacing it with a more “progressive” one. In April 1929, this issue began to be discussed in the press15. Initially, the talk was only about reforming the recreation system for Soviet workers. It was proposed to cancel all existing holidays and switch to a six-day week. It was planned to move the revolutionary holidays to the next day of rest, also using the evenings of working days. It was especially emphasized that the six-day week did not break the calendar system, since it left the same months and numbers of the year unchanged, with the exception of the “discarded extra day.” The introduction of the changed calendar was planned from January 1, 193016.

This proposal began a wide discussion of calendar reform. Soviet functionaries published propaganda articles calling for its speedy implementation. In particular, an employee of the USSR State Planning Committee L. M. Sabsovich considered changing the calendar one of the conditions for the speedy transition to a continuous production year17. He was supported by employee of the People's Commissariat of Labor B.V. Babin-Koren, who considered his main advantage new system chronology “maximum rigidity”18. In his opinion, this was expressed in a solid combination of working days and days off.

The editors of the Izvestia newspaper raised the issue of changing the calendar for discussion among readers. It evoked a lively response from them. Most proposals boiled down to the introduction of a five-day or six-day continuous week with one day off in the USSR19.

A. Pevtsov proposed his own project. His calendar consisted of ten days with two days off20. The year was divided into ten days (decades) and hundred days (tectads) and consisted of 36 decades and one additional half-decade (5 or 6 days). Pevtsov spoke in favor of abolishing months and motivated this with the following argument: since the number 36 was divisible by 2, 3,4, b, 9,12,18, then it is possible, if necessary, to divide the year into halves, thirds, quarters, etc. This might be necessary in Everyday life, when compiling reports, counting seasons. The names of the days of the week changed: the first day of the decade is Freedom Day; the second is Labor Day; third - Party Day; fourth - Defense Day; fifth - Victory Day; sixth - Day of Enlightenment; seventh - Union Day; eighth - Trade Union Day; ninth - Youth Day; tenth - Day of Remembrance. The first and sixth days were days of rest.

Similar projects were sent to the editorial offices of other newspapers. However, proposals to replace the names of months and days of the week with serial numbers did not meet with support everywhere. In particular, the editors of the Trade and Industrial Gazette considered them unacceptable and inappropriate21.

A special project was submitted for consideration to the USSR Academy of Sciences by the son of the great chemist I. D. Mendeleev22. He proposed dividing the year into 12 months of 30 days each. The week consisted of six days. Its introduction was determined by the ability to determine the fractional part of the year the same number weeks in a month; when calculating a month into 5 weeks, each of its numbers fell on the same days of the week. Each month had the same number of working days. An important advantage of the new calendar system, from the author’s point of view, was the presence of equal number of months between dates that had the same number of days and weeks: from February 5 to May 5 and from July 5 to October 5 there were 3 months, 15 weeks, 90 days. Five or six additional days were non-working days. They were assigned designations of events that were celebrated that day. After February, the Day of the Overthrow of the Autocracy was inserted, after April - May Day, after June - Constitution Day of the USSR, after August - Youth Day, after October - October Revolution Day. In a leap year, an additional day was inserted after December and was called Lenin's Memorial Day. The names of months and days remained unchanged. One day per week was abolished. Its name should have been clarified later.

In the fall of 1929, the issue of calendar reform was discussed at the very high level. One of the tasks of the government commission for the introduction of continuous production in the USSR was “the approval and publication of a new timesheet-calendar, necessary for a five-day and continuous production”23. One of the reports of the USSR People’s Commissariat of Labor emphasized that “changes in the working conditions of enterprises, the everyday habits of workers and employees require a corresponding adaptation of the calendar”24. It was specifically stated that the complexity of the issue lay in the need to compare it with the astronomical year and Western countries. Therefore, the adoption of a new calendar system needed careful consideration. On October 21, 1929, the Government Commission under the Council of Labor and Defense (SLO), chaired by V.V. Kuibyshev, instructed the People's Commissariat of Labor of the USSR to work on the issue of reforming the calendar in relation to the continuous production week25.

On December 28, a subcommittee on calendar reform was formed, headed by the People's Commissar of Education of the RSFSR A. S. Bubnov. Its work should have been completed no later than January 20, 193026. The commission held two meetings. The first was attended by astronomers S. N. Blazhko, N. I. Idelson, directors of the Moscow Planetarium K. N. Shistovsky and Pulkovo Observatory A. A. Ivanov and others. Three drafts of the new calendar were studied.

The first of them assumed the establishment of a solid calendar scale and determined the civil duration of the year at 360 days, with each month including 30 days. The remaining five days were revolutionary holidays and were excluded from the numbering, but remained in their original places.

The second option determined the length of the year to be 365 days. The days of revolutionary holidays were included in the general numbering of the days of the year. The project violated the principle of a fixed scale, but retained the duration of the working part of each month at 30 days. However, the physical duration of several months (April, November) was extended to 32 days.

The third option proposed replacing the existing seven-day week with a five-day week, leaving all calendar dates in their original places. He allowed only the establishment of a sliding scale for the distribution of rest days by number of months.

The meeting participants recognized the admissibility of the changes proposed in the projects. However, wishes were expressed related to establishing the same duration of the civil and tropical years and “possibly preserving the unity of the calendar dates of the new and Gregorian calendars”27. As a result, the majority spoke in favor of the first version of the calendar, proposing to establish in it new names for the days of the week that corresponded to the revolutionary calendar.

Representatives of the Supreme Economic Council M.Ya. Lapirov-Skoblo, the USSR State Planning Committee - G.I. Smirnov, the Astronomical Institute - N.I. Idelson, the director of the Pulkovo Observatory A.A. Ivanov and others were invited to the second meeting. The meeting, in addition to the projects mentioned above, accepted two new options for consideration - calendar French Revolution and the draft of the State Planning Committee of the RSFSR, developed by decision of the government commission under the Council of People's Commissars of the RSFSR dated October 15, 192928. The main provisions of the latest calendar were as follows. The length of the year is 365 days in simple and 366 in leap year, added once every four years. The chronology was established from the day of the October Revolution. The beginning of the social and economic years coincided and began on November 1. Their duration was 360 working days and 5 or 6 holidays. Each year was divided into 4 quarters of 90 days each, a quarter - into 3 equal months of 30 working days, a month - into 3 decades of 10 days or 6 weeks of 5 days each. The names of the months remained the same, but the names of the days changed. The first is Commune Day, the second is Marx Day, the third is Engels Day, the fourth is Lenin Day, the fifth is Stalin Day. Another innovation was leaving the days of the week without a name, using only serial numbers.

The majority of the commission members were in favor of the first option, proposed earlier. At the same time, wishes were expressed to introduce amendments to it arising from the draft of the State Planning Committee of the RSFSR. It was decided to combine both options in such a way as to eliminate the need to postpone the celebration of revolutionary days to new dates29.

On January 26, 1930, at a meeting of the government commission at the service station on the transfer of enterprises and institutions to a continuous production week, Bubnov’s report on the work done was heard. As a result, a resolution was issued approving the first version of the draft calendar with some additions. The new civil Soviet calendar was established with the constant coincidence of the numbers of months on the same day. The length of the year was 360 ordinary days and 5 or 6 holidays, which had the names of the first and second days of the Proletarian Revolution, the first and second days of the International and the day of memory of Lenin. These days were designated by the number of the previous day of the month with the addition of the letter A or B. The year was divided into 12 months of 30 working days in each month with the addition of the corresponding letter days. Each month was divided into 6 weeks of 5 days each. The names of months and days were retained, only Saturday and Sunday were abolished. The beginning civil year was considered the first day of the Proletarian Revolution.

The new calendar was planned to be introduced no later than February 25, 1930. For the final discussion and agreement on the main provisions of the project, the State Planning Committee was ordered to convene an interdepartmental meeting within a decade. After this, the final draft should have been submitted for approval to the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR30.

A conference at the USSR State Planning Committee spoke in favor of a new calendar. However, in her opinion, the beginning of the year and the names of the months should have been left unchanged. As a result, by decision of the government commission of service stations, a unified production timesheet was introduced in the country31. Its main difference from the existing chronology system was the inclusion of 360 working days and 5 non-working days. The so-called revolutionary days (January 22, May 1 and 2, November 7 and 8) were not included in the calendar. The employees of each enterprise or institution were distributed by the administration into five groups of equal numbers. For each of its members, a day off was set on a certain day of each five-day week: workers of the first group - on the first day, of the second group - on the second, and so on. Meetings of public, trade union and administrative organizations were to be held on the first, third and fifth days of the five-day week; Periodic meetings - throughout the year and on certain days. It was specifically stipulated that the resolution was in force “until the calendar reform was carried out.” Thus, a unified production calendar was also introduced for a certain period. This meant that the innovations were the first step towards a general calendar reform. After a few months, this project was planned to be introduced as a new civil calendar.

Over the next few years, civil and industrial calendars were used in parallel. However, the calendar reform in the USSR in the late 1920s and early 1930s was never implemented. The combination of industrial and civil calendars created great confusion in determining working days and days off. The situation was further complicated by the simultaneous use various organizations and institutions dependent on each other, a fixed and sliding scale of days off. At the same time, a fixed scale was established for management employees. This circumstance created additional difficulties in the work of enterprises, institutions and educational institutions, since the weekends of superiors and subordinates often did not coincide. There have been cases of overlap in teaching hours among teachers at various higher education institutions. educational institutions.

Despite attempts to resolve the situation by establishing a sliding scale of days off in all enterprises, institutions and educational institutions, the situation in better side hasn't changed. In the material presented by the People's Commissariat of Labor of the RSFSR to the government commission on the introduction of continuous production in the USSR on August 23, 1930, it was noted that “the experience of using a sliding scale has shown that with the existing general civil Gregorian (as in the text - E.N.) this scale is difficult for the population to assimilate, complicates the preparation of schedules, etc.”32.

Gradually, under the influence of economic and social factors, the idea of introducing continuous production was recognized as impossible and unpromising. This led to a gradual abandonment of its implementation. In turn, the idea of calendar reform died out. As a result, on June 26, 1940, the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR adopted a resolution “On the transition to an eight-hour working day, to a seven-day working week and on the prohibition of the unauthorized departure of workers and employees from enterprises and institutions”33. It returned the usual combination of working days and weekends to the USSR and put an end to attempts to change the calendar. The five-day period still remains in the public consciousness thanks to Grigory Alexandrov’s film “Volga-Volga”: it is quite difficult for a modern viewer to figure out what it is.

During the first years of the existence of Soviet power, the calendar issue played a significant role in the socio-political life of the country. The failure of the plan to create a revolutionary calendar was explained by several factors. These included the discrepancy between the Soviet calendar system and the chronology of foreign countries. This caused confusion in international relations. This fact was recognized in Soviet literature. One of the ideologists of the new economic system, writer I. L. Kremlev-Sven, considered one of the most serious obstacles to the introduction of a new calendar “the possibility of disagreement with foreign countries”34. Another reason was the non-acceptance of the new calendar by the majority of the population of the USSR. This caused confusion in the definition of working days and weekends, vacation dates, gave rise to absenteeism and overall reduced the economic well-being of the country. Due to these circumstances, the Soviet government refused to change the chronology system, leaving the Gregorian calendar in civilian use.

Notes

1. Decrees of the Soviet government. T. 1. M. 1957. No. 272. P. 404-405.

2. Holy Council of the Orthodox Russian Church. Acts. Book VI. Vol. 2. M. 1918. pp. 132-133.

3. GARF. F. R-3431. D. 74. L. 86 vol.

4. Ibid. L. 39, 60 rev.

5. Ibid. D. 283. L. 354-355.

6. Ibid. L. 431.

7. Ibid. L. 432.

8. Ibid. L. 463 vol., 663.

9. Ibid. L. 86 rev; Holy Council of the Orthodox Russian Church. Acts. Book VI. Vol. 2. C 188.

10. Resolution of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon and the Small Council of Bishops on the transition to a new (Gregorian) style in liturgical practice dated 24.09 (7.10) // Acts of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon and later documents on the succession of supreme church authority 1917-1943. Part 1. M. 1994. P. 299.

11. Message of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon to the Orthodox people

on calendar reform in Russian Orthodox Church from 18.09 (1.10). 1923//Investigative case of Patriarch Tikhon. M. 2000. No. 186. P. 361.

12. Order (“resolution”) of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon on the abolition of the “new” (Gregorian) calendar style in liturgical practice dated October 26 (November 8), 1923 // Investigative case... No. 187. From 362-363.

13. Statement of His Holiness Patriarch Tikhon to the Central Executive Committee on the attitude of the Orthodox Russian Church to the calendar reform (transition to the Gregorian “new” style) from

17 (30) 09. 1924//Acts... 4.1. P. 337.

14. Ibid. P. 337.

15. Dubner P. M. Soviet calendar // Ogonyok. 1929. No. 40; Viktorov Yu. We need an initiative // Izvestia of the Central Election Commission USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets. 1929. No. 98. P. 5; Kaygorodov

A. We need to reform the week//Ibid. S. 5; Kremlev I. L. Continuous production and socialist construction. M.; L. 1929. P. 108-115.

16. Baranchikov P. Not holidays, but days of rest // News of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets. 1929. No. 86. P. 3.

17. Sabsovich L. M. It is more decisive to switch to a continuous production year // Trade and industrial newspaper. 1929. No. 173. P. 3.

18. Babin-Koren B.V. Standardization of the calendar grid // Trade and industrial newspaper. 1929. No. 223. P. 3.

19. Motives for the five-day week (review of reader letters) // News of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets. 1929. No. 199. P. 3; Friday//Ibid; 0 six-day week // Ibid. No. 203. P. 3.

20. Pevtsov A. For a decade with two days of rest // News of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets. 1929. No. 199. P. 3.

21. P. D. First steps of continuity. For the reform of the calendar//Commercial and industrial newspaper. 1929.

No. 249. P. 5.

22. Six-day project at the Academy of Sciences // News of the Central Executive Committee of the USSR and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets. 1929. No. 203. P. 3.

23. GARF. F. R-7059. On. 1. D. 7. L. 15.

24. Ibid. D. 2. L. 4.

25. Ibid. D. 4. L. 22, 25.

26. Ibid. L. 24 rev., 52 rev.

27. Ibid. L. 41.

28. Ibid. D. 6. L. 12.

29. Ibid. D. 4. L. 41.

30. Ibid. L. 28 rev.

31. Resolution of the government commission under the Council of Labor and Defense. “0 transfer of enterprises and institutions to a continuous production week” // Labor. 1930. No. 74. P. 4.

32. GARF. F. R-7059. On. 1. D. 2. L. 444, 505.

33. Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of June 26, 1940

“0 transition to an eight-hour working day, to a seven-day working week and the prohibition of unauthorized departure of workers and employees from enterprises and institutions” // Gazette of the Supreme Council of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. 1940. No. 20. P. 1.

34. Kremlev-Sven I. L. Two conversations about the continuous week. M. 1930. P. 27.