You write about the baron in the castle - if you please at least roughly imagine how the castle was heated, how it was ventilated, what was illuminated ...

From an interview with G.L. Oldie

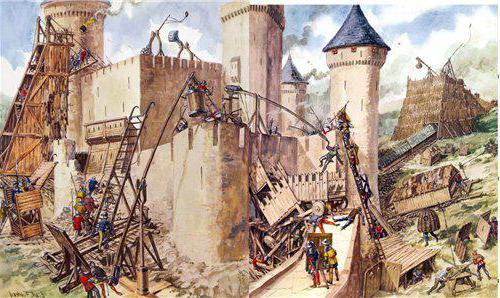

With the word “castle” in our imagination, an image of a majestic fortress arises - a visiting card of the fantasy genre. There is hardly any other architectural structure that would attract so much attention from historians, military experts, tourists, writers and lovers of “fairy-tale” fiction.

We play computer, board and role-playing games where we have to explore, build or capture impregnable castles. But do we know what these fortifications really are? What interesting stories are connected with them? What do the stone walls hide behind themselves - witnesses of whole eras, grandiose battles, knightly nobility and vile betrayal?

Surprisingly, the fact is that the fortified dwellings of the feudal lords in different parts of the world (Japan, Asia, Europe) were built on very similar principles and had many common design features. But in this article we will focus primarily on medieval European feudal fortresses, since they served as the basis for creating a mass artistic image of the “medieval castle” as a whole.

The birth of the fortress

The Middle Ages in Europe were a turbulent time. For any reason, the feudal lords arranged small wars among themselves — or rather, not even wars, but, to use modern terms, armed “showdowns”. If a neighbor got money, they had to be taken away. A lot of land and peasants? This is simply indecent, because God ordered to share. And if knightly honor is affected, then here without a small victorious war it was simply not enough.

Under such circumstances, the large landowner aristocrats had no choice but to strengthen their homes with the expectation that one day neighbors might come to visit them, whom you don’t feed with bread - let someone slaughter.

Initially, these fortifications were made of wood and did not resemble the castles known to us - except that a ditch was dug in front of the entrance and a wooden picket fence was set around the house.

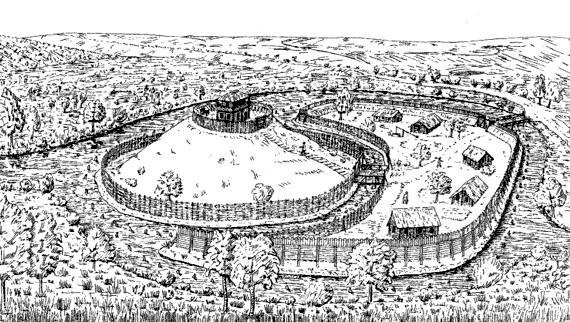

The courtyards of Hasterknaup and Elmendorv are the ancestors of castles.

However, progress did not stand still - with the development of military affairs, the feudal lords had to modernize their fortifications so that they could withstand a massive assault using stone cores and rams.

The European castle is rooted in antiquity. The earliest structures of this kind were copied by Roman military camps (tents surrounded by a palisade). It is believed that the tradition of building gigantic (by the standards of the time) stone structures began with the Normans, and classical castles appeared in the 12th century.

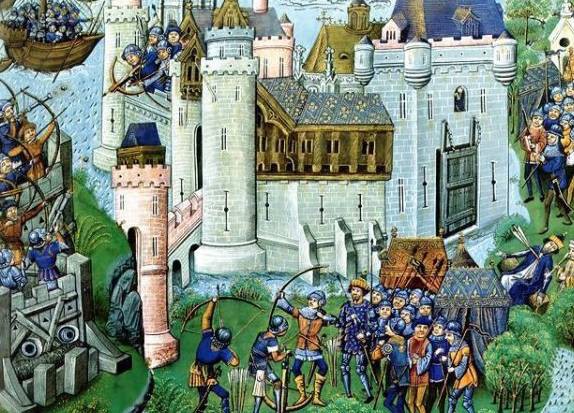

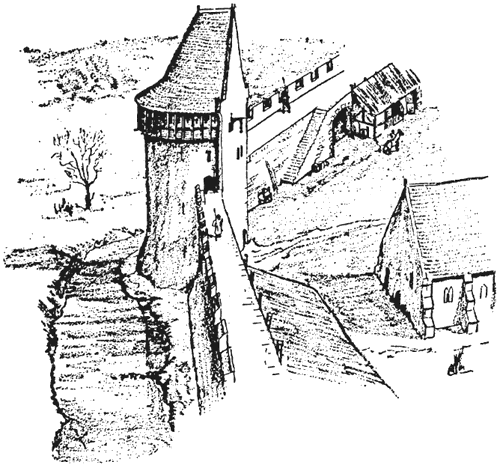

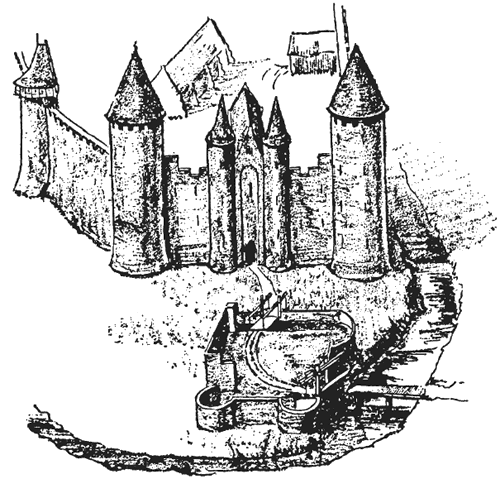

The besieged castle of Mortan (withstood the siege of 6 months).

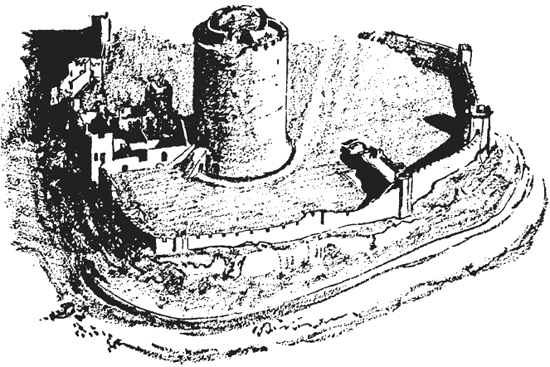

The castle had very simple requirements - it must be inaccessible to the enemy, provide surveillance of the area (including the nearest villages belonging to the owner of the castle), have its own source of water (in case of siege) and perform representative functions - that is, show the power and wealth of the feudal lord.

Bomari Castle, owned by Edward I.

Welcome

We keep our way to the castle, which stands on a ledge of a mountainside, on the edge of a fertile valley. The road goes through a small settlement - one of those that usually grew near the fortress wall. Simple people live here - mainly artisans, and warriors guarding the outer perimeter of protection (in particular, guarding our road). This is the so-called “castle people”.

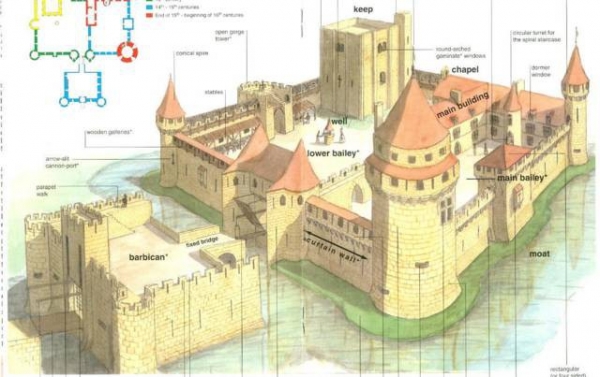

The scheme of castle structures. Note - two gate towers, the largest stands separately.

The road is laid in such a way that the aliens are always facing the castle with their right side, not covered by a shield. Directly in front of the fortress wall there is a bare plateau lying under a significant slope (the castle itself stands on an elevation - natural or bulk). The vegetation is low so that there is no shelter for the attackers.

The first barrier is a deep ditch, and in front of it is a shaft of excavated earth. The moat can be transverse (separates the castle wall from the plateau), or crescent, curved forward. If the landscape allows, the moat encircles the entire castle in a circle.

Sometimes ditches dug up inside the castle, making it difficult for the enemy to move through its territory.

The shape of the bottom of the ditches could be V-shaped and U-shaped (the latter is the most common). If the soil under the castle is rocky, then the ditches were either not made at all, or they were cut down to a shallow depth, preventing only the advancement of infantry (in the rock it is almost impossible to dig under the castle wall - therefore, the depth of the ditch was not critical).

The crest of the earthen rampart, lying directly in front of the moat (which makes it seem even deeper), often carried a palisade - a fence of wooden stakes dug into the ground, pointed and tightly fitted to each other.

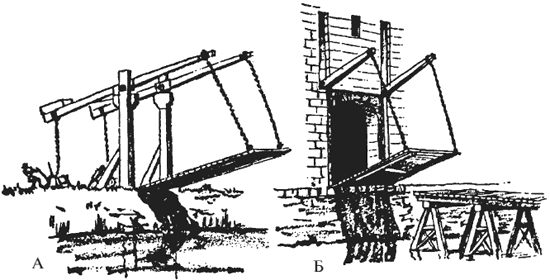

A bridge over the moat leads to the outer wall of the castle. Depending on the size of the moat and bridge, the latter supports one or more supports (huge logs). The outer part of the bridge is fixed, but its last segment (directly against the wall) is movable.

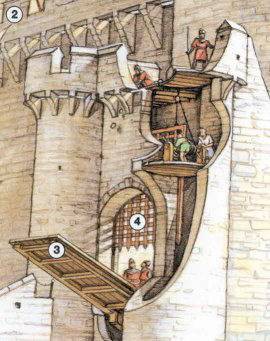

The scheme of entrance to the castle: 2 - gallery on the wall, 3 - drawbridge, 4 - lattice.

Counterweights on the gate lift.

The gates of the castle.

This drawbridge is designed so that in an upright position it closes the gate. The bridge is set in motion by mechanisms hidden in the building above them. Ropes or chains go from the bridge to the lifting machines into the wall openings. To facilitate the work of people servicing the bridge mechanism, the ropes were sometimes equipped with heavy counterweights, taking on part of the weight of this structure.

Of particular interest is the bridge, which worked on the principle of a swing (it is called “tipping” or “swinging”). One half of it was inside - lying on the ground under the gate, and the other stretching across the moat. When the inner part rose, blocking the entrance to the castle, the outer one (which the attackers sometimes managed to run into) fell down into the moat where the so-called “wolf pit” (sharp stakes dug into the ground) was arranged, invisible from the side, while the bridge is down.

To enter the castle with the gates closed, there was a side gate next to them, to which a separate lifting ladder is usually laid.

Gates - the most vulnerable part of the castle, were usually not done directly in its wall, but were arranged in the so-called “gate towers”. Most often, the gates were double-leaf, with the sash being knocked together from two layers of boards. To protect against arson from the outside, they were studded with iron. At the same time, in one of the wings there was a small narrow door, which could be entered only by bending. In addition to locks and iron bolts, the gates were closed by a transverse beam lying in the wall channel and sliding into the opposite wall. The crossbeam could also wind into hook-like slots on the walls. Its main goal was to protect the gate from being planted by attackers.

Behind the gate there was usually a lowering grate. Most often, it was wooden, with iron ends tied to iron. But there were also iron gratings made of steel tetrahedral rods. The lattice could fall from the gap in the arch of the portal of the gate, or be behind them (on the inside of the gate tower), falling along the grooves in the walls.

The grate hung on ropes or chains, which in case of danger could be cut off so that it quickly fell down, blocking the path of the invaders.

Inside the gate tower there were guard rooms. They kept watch on the upper platform of the tower, learned from the guests the purpose of their visit, opened the gates, and if necessary, could strike from the bow all those who passed under them. To do this, in the arch of the portal portal there were vertical loopholes, as well as “tar noses” - holes for pouring hot resin on the attackers.

Tar noses.

All to the wall!

The most important defensive element of the castle was the outer wall - high, thick, sometimes on an inclined base. Treated stones or bricks made up its outer surface. Inside, it consisted of rubble and slaked lime. The walls were laid on a deep foundation, under which it was very difficult to dig.

Often double walls were built in castles - a high external and a small internal one. Between them there was an empty place, which received the German name “Zwinger”. The attackers, overcoming the outer wall, could not take with them additional assault devices (bulky stairs, poles and other things that cannot be carried inside the fortress). Finding themselves in front of yet another wall in the zwinger, they became an easy target (there were small loopholes for the archers in the zwinger walls).

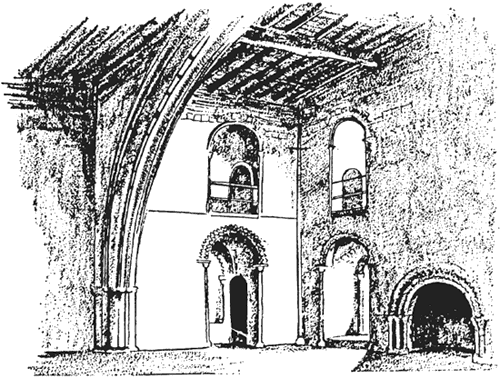

Zwinger at Laneck Castle.

Above the wall was a gallery for defense soldiers. From the outside of the castle they were protected by a solid parapet half of human growth, on which stone battlements were regularly located. Behind them one could stand at full height and, for example, load a crossbow. The shape of the teeth was extremely diverse - rectangular, rounded, in the form of a dovetail, decoratively decorated. In some castles, the galleries were covered (wooden canopy) to protect the soldiers from the weather.

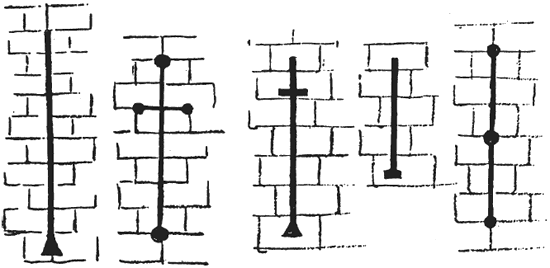

In addition to the battlements, which were convenient to hide behind, the castle walls were equipped with loopholes. Through them, attackers were fired. In view of the peculiarities of the use of throwing weapons (freedom of movement and a certain shooting position), loopholes for archers were long and narrow, and for crossbowmen short, with expansion on the sides.

A special type of loophole is ball. It was a wooden ball fixed in the wall, freely turning with a slot for firing.

Pedestrian gallery on the wall.

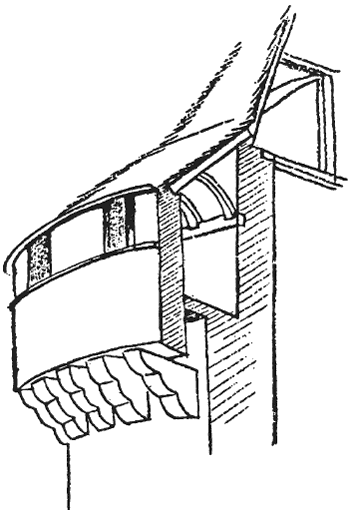

Balconies (the so-called “mashikuli”) were very rarely arranged in the walls - for example, when the wall was too narrow for several soldiers to freely pass, and, as a rule, performed only decorative functions.

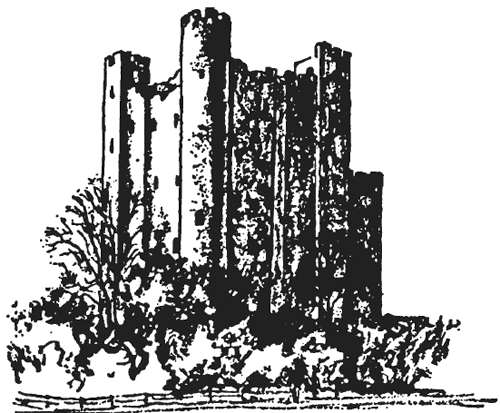

In the corners of the castle, small towers were built on the walls, most often flanking (that is, protruding outward), which allowed the defenders to fire along the walls in two directions. In the late Middle Ages, they began to adapt to storage facilities. The inner sides of such towers (facing the castle courtyard) were usually left open so that the enemy, breaking into the wall, could not gain a foothold inside them.

Flanking corner tower.

Castle inside

The internal structure of the locks was diverse. In addition to the mentioned zwingers, behind the main gate there could be a small rectangular courtyard with loopholes in the walls - a kind of “trap” for attackers. Sometimes the locks consisted of several “sections” separated by internal walls. But an indispensable attribute of the castle was a large courtyard (outbuildings, a well, rooms for servants) and the central tower, it is also a “donjon”.

Donjon in the castle of Vincennes.

The life and the location of the well directly depended on the life of all the inhabitants of the castle. He often had problems - after all, as already mentioned above, castles were built on elevations. Strong rocky soil also did not facilitate the task of supplying the fortress with water. There are known cases of laying castle wells to a depth of more than 100 meters (for example, the Kuffheuser castle in Thuringia or the Königstein fortress in Saxony had wells with a depth of more than 140 meters). Digging a well took from one year to five years. In some cases, it absorbed as much money as all the castle’s internal buildings cost.

Due to the fact that it was difficult to get water from deep wells, issues of personal hygiene and sanitation faded into the background. Instead of washing themselves, people preferred to take care of animals - first of all, expensive horses. It is not surprising that the townspeople and villagers wrinkled their noses in the presence of the inhabitants of the castles.

The location of the water source depended primarily on natural causes. But if there was a choice, then the well was dug out not in the square, but in a fortified room to provide it with water in case of shelter during the siege. If, due to the peculiarities of the occurrence of groundwater, a well was dug outside the castle wall, then a stone tower was built over it (if possible, with wooden passages to the castle).

When there was no way to dig a well, a cistern was built in the castle collecting rainwater from the roofs. Such water needed to be purified - it was filtered through gravel.

The military garrison of castles in peacetime was minimal. So in 1425, two co-owners of the Reichelsberg castle in the Nizhne-Franconian Aube entered into an agreement that each of them exposes one armed servant, and two gatekeepers and two guards are paid together.

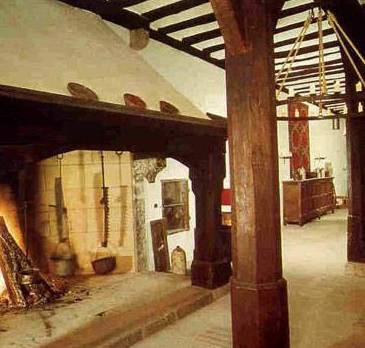

The castle also had a number of buildings providing an autonomous life of its inhabitants in conditions of complete isolation (blockade): a bakery, a steam bath, a kitchen, etc.

Kitchen in the castle of Marxburg.

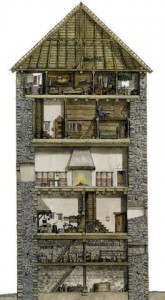

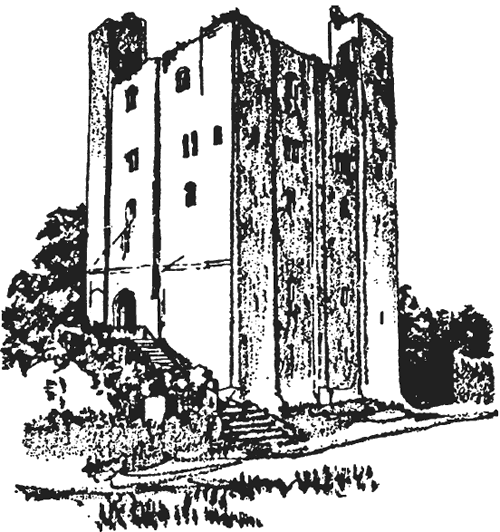

The tower was the tallest building in the entire castle. It provided the opportunity to observe the surroundings and served as the last refuge. When enemies broke through all lines of defense, the castle’s population took refuge in the dungeon and withstood a long siege.

The exceptional thickness of the walls of this tower made its destruction virtually impossible (in any case, it would take a huge amount of time). The entrance to the tower was very narrow. It was located in the courtyard at a considerable (6-12 meters) height. The wooden staircase leading inward could easily be destroyed and thus blocked the way for the attackers.

Entrance to the dungeon.

Inside the tower, there was sometimes a very high shaft running from top to bottom. She served as either a prison or a warehouse. Entrance into it was possible only through an opening in the arch of the upper floor - “Angstloch” (German - a frightening hole). Depending on the purpose of the mine, the winch lowered prisoners or provisions there.

If there were no prison premises in the castle, then the captives were placed in large wooden boxes made of thick boards, too small to stand up to their full height. These boxes could be installed in any premises of the castle.

Of course, they were taken prisoner, first of all, to obtain a ransom or to use the prisoner in the political game. Therefore, VIP-persons were provided in the highest class - for their maintenance, protected chambers in the tower stood out. That is how Frederick the Beautiful “wound his term” in the castle of Trausnits on Pfaimde and Richard the Lionheart in Trifels.

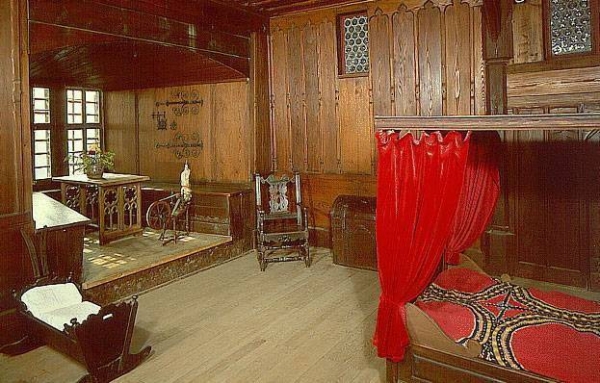

Chamber in the castle of Marxburg.

Abenberg castle tower (12th century) in section.

At the base of the tower were a basement, which could also be used as a dungeon, and a kitchen with a pantry. The main hall (dining room, common room) occupied an entire floor and was heated by a huge fireplace (it spread heat only a few meters, so that iron baskets with coals were placed further down the hall). Above were the chambers of the feudal lord's family, heated by small stoves.

At the very top of the tower there was an open (less often - covered, but if necessary, roof could be dropped) platform, where it was possible to install a catapult or other throwing weapon for shelling the enemy. The standard (banner) of the owner of the castle was hoisted there.

Sometimes the dungeon did not serve as a living room. It could well be used only for military purposes (observation posts on the tower, dungeon, storage of provisions). In such cases, the feudal lord’s family lived in the “palace”, the castle’s living quarters, which was separate from the tower. The palaces were built of stone and had several floors in height.

It should be noted that the living conditions in the castles were far from the most pleasant. Only the largest palaces had a large knight's hall for celebrations. It was very cold in the donjon and the palace. Fireplace heating came to the rescue, but the walls were still covered with thick tapestries and carpets - not for decoration, but to preserve heat.

The windows passed very little sunlight (the fortification character of the castle architecture affected), far from all of them were glazed. Toilets were arranged in the form of a bay window in the wall. They were unheated, so visiting the nursery in winter left people with a unique feeling.

Castle toilet.

Concluding our “tour” of the castle, it is impossible not to mention the fact that there was definitely a room for worship in it (temple, chapel). Among the indispensable inhabitants of the castle was a chaplain or priest, who, in addition to his main duties, played the role of a clerk and teacher. In the most modest fortresses, the role of the temple was played by a wall niche where a small altar stood.

Large temples had two floors. The common people prayed below, and the gentlemen gathered in a warm (sometimes glazed) choir on the second tier. The decoration of such premises was rather modest - an altar, benches and wall paintings. Sometimes the temple served as a tomb for the family living in the castle. Less commonly, it was used as a refuge (along with a dungeon).

Many underground tales tell about underground passages in castles. The moves, of course, were. But only very few of them led from the castle somewhere to the neighboring forest and could be used as a way to escape. Long moves, as a rule, were not at all. Most often there were short tunnels between individual buildings, either from the donjon to the complex of caves under the castle (additional shelter, warehouse or treasury).

Hello dear reader!

Still, medieval architects in Europe were geniuses - they built castles, luxurious buildings, which were also extremely practical. Castles, unlike modern mansions, not only demonstrated the wealth of their owners, but also served as powerful fortresses that could hold the defense for several years, and at the same time life in them did not stop.

Medieval castles

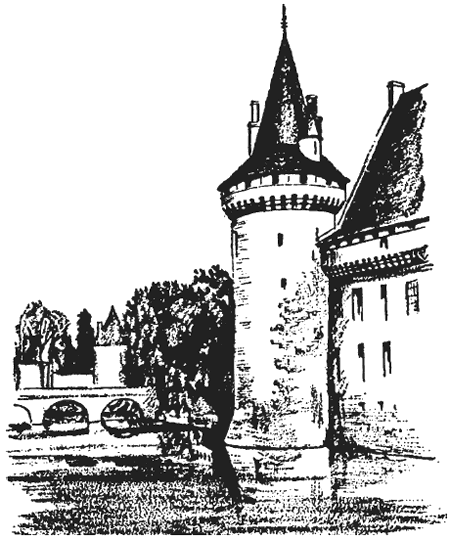

Even the fact that many castles, having survived wars, natural disasters and the carelessness of the owners, are still intact, suggests that they have not yet come up with more reliable homes. And they are insanely beautiful and seemed to have appeared in our world from the pages of fairy tales and legends. Their high spiers remind of the times when the hearts of beautiful women fought, and the air was saturated with chivalry and courage.

In order for you to feel the romantic mood, I collected in this material the 20 most famous castles that have still remained on Earth. They will certainly want to visit them and, possibly, stay alive.

Reichsburg Castle, Germany

The millennium castle was originally the residence of the King of Germany Conrad III, and then the King of France Louis XIV. The fortress was burned by the French in 1689 and would have sunk into oblivion, but a German businessman acquired its remains in 1868 and spent most of its wealth on rebuilding the castle.

Mont Saint Michel, France

The impregnable castle of Mont Saint-Michel, surrounded on all sides by the sea, is one of the most popular sights of France after Paris. Built in 709, it still looks stunning.

Hochosterwitz Castle, Austria

The medieval castle of Hochosterwitz was built in the distant 9th century. Its towers are now vigilantly monitoring the surrounding area, proudly towering above it at an altitude of 160 m. And in sunny weather you can admire them even at a distance of 30 km

Bled Castle, Slovenia

The castle is located on a hundred-meter-high cliff menacingly hanging over Lake Bled. In addition to the magnificent view from the castle windows, this place has a rich history - here was the residence of the Serbian queen of the dynasty, and later of Marshal Josip Broz Tito

Hohenzollern Castle, Germany

This castle is located on the top of the Hohenzollern mountain with a height of 2800 meters above sea level. During its heyday, the castle in this fortress was considered the residence of the Prussian emperors.

Barciense Castle, Spain

Barsiense Castle in the Spanish province of Toledo was built in the 15th century by a local count. For 100 years, the castle served as a powerful artillery fortress, and today these empty walls attract only photographers and tourists.

Neuschwanstein Castle, Germany

The romantic castle of the Bavarian king Ludwig II was built in the middle of the XIX century, and at that time its architecture was considered very extravagant. Be that as it may, it was its walls that inspired the creators of Sleeping Beauty Castle at Disneyland

Methoni Castle, Greece

From the 14th century, the Venetian castle-fortress Methoni has been the center of battles and the last outpost of Europeans in these lands in battles against the Turks that they dreamed of capturing Pelopones. Today, only ruins remained from the fortress.

Hohenschwangau Castle, Germany

This castle was built by the Knights of Schwangau in the XII century and was the residence of many rulers, including the famous King Ludwig II, who hosted the composer Richard Wagner in these walls

Chillon Castle, Switzerland

This medieval bastille from a bird's eye view resembles a warship. The rich history and characteristic appearance of the castle served as an inspiration for many famous writers. In the XVI century the castle was used as a state prison, which George Byron described in his poem "Prisoner of Chillon".

Eilean Donan Castle, Scotland

The castle, located on a rocky island in the Loch Duych fjord, is one of Scotland's most romantic castles, famous for its heather honey and legends. Many films were shot here, but the most important thing is that the castle is open to visitors and everyone can touch the stones of its history.

Bodiam Castle, England

Since its founding in the XIV century, Bodiam Castle has survived many owners, each of whom liked to fight. Therefore, when Lord Curzon acquired it in 1917, only ruins remained of the castle. Fortunately, its walls were quickly restored, and now the castle stands as good as new.

Guaita Castle, San Marino

Since the 11th century, the castle has been located on top of the impregnable Monte Titano mountain and, together with two other towers, protects the oldest state in the world, San Marino.

Swallow's Nest, Crimea

At first, a small wooden house was located on the cliff of Cape Ai-Todor. And the Swallow's Nest got its present look thanks to the oil industrialist Baron Steingel, who liked to rest in Crimea. He decided to build a romantic castle that resembles medieval buildings on the banks of the Rhine River

Stalker Castle, Scotland

Stalker Castle, which means "Falconer", was built in 1320 and belonged to the MakDugalov clan. Since that time, its walls have experienced a huge amount of strife and war, which affected the state of the castle. In 1965, the owner of the castle was Colonel D.R. Stuart of Allvard, who restored the building with his own wife, family members and friends

Bran Castle, Romania

Bran Castle is the pearl of Transylvania, the mysterious fort museum where the famous legend of Count Dracula, the vampire, murderer and governor Vlad Tepes, was born. According to legend, he spent the night here during the periods of his campaigns, and the forest surrounding Bran Castle was the favorite hunting ground of Tepes.

Vyborg Castle, Russia

The Vyborg castle was founded by the Swedes in 1293, during one of the crusades on Karelian land. He remained Scandinavian until 1710, when the troops of Peter I drove the Swedes away for a long time. Since that time, the castle managed to visit both the warehouse and the barracks, and even the prison for the Decembrists. And nowadays there is a museum.

Castle Cough, Ireland

Cashel Castle was the residence of the kings of Ireland several hundred years before the Norman invasion. Here in the 5th century AD e. St. Patrick lived and preached. The walls of the castle witnessed the bloody suppression of the revolution by the troops of Oliver Cromwell, who here burned the soldiers alive. Since then, the castle has become a symbol of the cruelty of the British, real courage and steadfastness of the spirit of the Irish.

Kilhurn Castle, Scotland

Very beautiful and even a little creepy ruins of the castle of Kilhurn are located on the banks of the picturesque Lake Av. The history of this castle, unlike most of the castles of Scotland, proceeded quite calmly - there lived numerous counts who succeeded each other. In 1769, the building suffered from a lightning strike, and was soon finally abandoned, which remains to this day.

Lichtenstein Castle, Germany

Built in the 12th century, this castle was destroyed several times. It was finally restored in 1884 and since then the castle has become the filming location for many films, including the film “Three Musketeers”.

Castles of feudal lords still attract admiring glances. It is hard to believe that life flowed in these sometimes fabulous constructions: people organized life, raised children, took care of subjects. Many castles of the feudal lords of the Middle Ages are protected by the states in which they are located, because their arrangement and architecture are unique. However, all these structures have a number of common features, because their functions were the same and proceeded from the lifestyle and state essence of the feudal lord.

The feudal lords: who they are

Before talking about what the feudal castle looked like, we will consider what kind of class it was in medieval society. European states were then monarchies, but the king, who was at the top of power, did little to decide. Power was concentrated in the hands of the so-called lords - they were the feudal lords. Moreover, within this system there was also a hierarchy, the so-called Knights stood on its lower tier. The feudal lords, who are one step higher, were called vassals, and the vassal-senor relations were preserved exclusively for the nearby levels of the stairs.

Each seigneur had his own territory, on which the feudal lord’s castle was located, a description of which we will definitely give below. Also here lived subordinates (vassals) and peasants. Thus, it was a kind of state in the state. That is why in a situation, called that very weakened the country.

Relations between the feudal lords were not always good-neighborly, there were frequent cases of hostility between them, attempts to conquer territories. The possession of the feudal lord was to be well fortified and protected from attack. Actually its functions we will consider in the next part.

The main functions of the castle

The very definition of “castle” implies an architectural structure that combines economic and defensive tasks.

Proceeding from this, the feudal lord's castle performed the following functions:

1. Military. The construction was not just to protect the inhabitants (the owner himself and his family), but also the servants, colleagues, vassals. In addition, it was here that the headquarters of military operations was stationed.

2. Administrative. The castles of the feudal lords were a kind of centers from where the land was administered.

3. Political. State issues were also resolved in the seigneur’s possessions, hence orders were given to local managers.

4. Cultural. The atmosphere prevailing in the castle allowed the subjects to get an idea of \u200b\u200bthe latest fashion trends - whether it be clothes, trends in art or music. In this matter, the vassals have always focused on their lord.

5. Household. The castle was a center for peasants and artisans. This concerned both administrative matters and trade.

The feudal castle, described in this article, and the fortress will be wrong. There are fundamental differences between them. Fortresses were called upon to protect not only the owner of the territory, but also all residents without exception, while the castle was exclusively for the feudal lord living in it, his family and the closest vassals.

A fortress is a fortification of a certain piece of land, and a castle is a defensive structure with developed infrastructure, where each element performs a specific function.

Prototypes of feudal castles

The first structures of this kind appeared in Assyria, then Ancient Rome adopted this tradition. Well, after the feudal lords of Europe - mainly Great Britain, France and Spain - they began building their castles. Often it was possible to see such buildings in Palestine, because then, in the XII century, the Crusades were in full swing, respectively, the conquered lands had to be held and defended by the construction of special structures.

The trend of castle building disappears along with feudal fragmentation when European states become centralized. Indeed, now it was possible not to be afraid of the attacks of a neighbor encroaching on someone else's.

Special, protective, functionality is gradually giving way to an aesthetic component.

External Description

Before disassembling the structural elements, let’s imagine what the feudal lord’s castle looked like in general. The first thing that caught my eye was a moat encircling the entire territory on which the monumental structure stood. Next was a wall with small turrets to repel the enemy.

Only one entrance led to the castle - a drawbridge, then an iron grate. Above all other buildings towered the main tower, or dungeon. The necessary infrastructure was also located in the courtyard outside the gates: workshops, a forge and a mill.

It should be said that the place for the building was carefully chosen, it had to be a hill, a hill or a mountain. Well, if you were able to choose the territory to which at least on one side there was a natural body of water - a river or a lake. Many note how raptors' nests and castles look like (photo for an example below) - both of them were famous for their impregnability.

Castle Hill

We will understand the structural elements of the structure in more detail. The hill for the castle was a hill of the correct form. As a rule, the surface was square. The height of the hill was on average from five to ten meters, there were structures and above this mark.

Particular attention was paid to the breed from which the bridgehead for the castle was made. As a rule, clay was used; peat and limestone rocks were also used. They took material from the ditch, which was dug around the hill for greater protection.

Flooring on the hillsides made of brushwood or planks were also popular. There was also a staircase.

Moat

In order to slow down the attack of a potential enemy for some time, as well as to make it difficult to transport siege weapons, a deep moat with water was needed that encircled the hill on which the castles were located. The photo shows how this system functioned.

It was necessary to fill the moat with water - this guaranteed that the enemy would not undermine the castle. Water was most often supplied from a natural reservoir located nearby. The moat had to be cleaned regularly of garbage, otherwise it was shallow and could not fully perform its protective functions.

Also, there were cases when logs or stakes were mounted in the bottom, which prevented the crossing. For the owner of the castle, his family, citizens and guests, a draw bridge was provided, which led directly to the gate.

Goal

In addition to its direct function, the gate performed a number of others. The castles of the feudal lords had a very secure entrance, which during the siege was not so easy to capture.

The gates were equipped with a special heavy-weight grille, having the form of a wooden frame with thick iron rods. If necessary, she descended to delay the enemy.

In addition to the guards standing at the entrance, on both sides of the gate there were two towers on the fortress wall for a better view (the entrance area was the so-called “blind zone.” There were not only sentries, but also archers on duty.

Perhaps the most vulnerable part of the gate was the gate - an acute need for its protection arose at night, because the entrance to the castle was closed at night. Thus, it was possible to track everyone who visits the territory at "inopportune" times.

Courtyard

Having passed the control of the guards at the entrance, the visitor got into the courtyard, where one could observe real life in the castle of the feudal lord. Here were all the main outbuildings and work was in full swing: warriors trained, blacksmiths forged weapons, artisans made the necessary household items, servants performed their duties. There was also a well with drinking water.

The area of \u200b\u200bthe courtyard was not large, which made it possible to monitor everything that was happening on the territory of the seigneur's possession.

Donjon

The element that always catches your eye when you look at the castle is the dungeon. This is the highest tower, the heart of any dwelling of the feudal lord. It was located in the most inaccessible place, and the thickness of its walls was such that it was very difficult to destroy this structure. This tower provided the opportunity to observe the surroundings and served as the last refuge. When enemies broke through all lines of defense, the castle’s population took refuge in the dungeon and withstood a long siege. At the same time, the dungeon was not only a defensive structure: the feudal lord and his family lived here at the highest level. Below are servants and warriors. Often inside this building was a well.

The lowest floor is a huge hall where magnificent feasts took place. At the oak table, which was bursting with all kinds of dishes, the feudal lord and himself were seated.

The internal architecture is interesting: spiral staircases were hidden between the walls, along which it was possible to move between levels.  Moreover, each of the floors was independent of the previous and subsequent. This provided additional security.

Moreover, each of the floors was independent of the previous and subsequent. This provided additional security.

The donjon had stockpiles of weapons, food and drink in case of siege. The products were kept on the highest floor so that the feudal lord's family was provided and did not starve.

Now consider another question: how comfortable were the feudal lords? Unfortunately, this quality suffered. Analyzing the story of the feudal lord’s castle, heard from the mouth of an eyewitness (a traveler who visited one of these sights), we can conclude that it was very cold there. No matter how the servants tried to flood the premises, nothing worked, the halls were too huge. It was also noted the lack of a cozy home and the uniformity of the “chopped” rooms.

Wall

Almost the most important part of the castle, which was owned by a medieval feudal lord, was the fortress wall. She surrounded the hill on which the main building stood. Special requirements were put forward against the walls: impressive height (so that the stairs were not enough for a siege) and strength, because not only human resources, but also special devices were often used for the assault. The average parameters of such structures: 12 m in height and 3 m in thickness. Impressive, isn't it?

The observation towers crowned the wall in each of its corners, in which sentries and archers were on duty. In the area of \u200b\u200bthe castle bridge there were also special places on the wall so that the besieged could effectively repel the attack of the attackers.

In addition, along the entire perimeter of the wall, along its very top, there was a gallery for defense soldiers.

Life in the castle

How did life proceed in a medieval castle? The second person after the feudal lord was the manager, who kept records of the peasants and artisans subordinate to the owner who worked on the estate. This person took into account how much production was produced and brought, how much the vassals paid for the use of land. Often the manager worked in tandem with the clerk. Sometimes they provided for a separate room in the castle.

The staff of the servants included immediate servants helping the owner and mistress, there was also a cook with assistant cooks, a stoker - a person responsible for heating the room, a blacksmith and a saddler. The number of servants was directly proportional to the size of the castle and the status of the feudal lord.

The large room was hard enough to heat. The stone walls cooled significantly at night, in addition, they absorbed moisture greatly. Therefore, the rooms were always damp and cold. Of course, the stokers tried their best to keep warm, but this was not always possible. Particularly wealthy feudal lords could afford the decoration of the walls with wood or carpets, tapestries. To save as much heat as possible, the windows were made small.

For heating, limestone stoves were used, which were located in the kitchen, from where the heat spread to nearby rooms. With the invention of pipes, it became possible to heat other rooms of the castle. Tiled stoves created special comfort for the feudal lords. A special material (burnt clay) made it possible to heat large areas and retained heat better.

What did they eat in the castle

An interesting diet of castle residents. Here, social inequality is best traced. Most of the menu was meat dishes. And it was perfect beef and pork.

No less important place on the feudal table was occupied by agricultural products: bread, wine, beer, porridge. The tendency was as follows: the more noble the feudal lord - the brighter the bread on his table. It's no secret that this depends on the quality of the flour. The percentage of grain products was maximum, and meat, fish, fruits, berries and vegetables were only a pleasant addition.

A special feature of cooking in the Middle Ages was the abundant use of seasonings. And here, more than the peasantry could afford to know. For example, African or Far Eastern spices, which at a cost (for a small capacity) were not inferior to cattle.

Since the seas and rivers provided a great overview for tracking and attacking foreign invaders.

The water supply made it possible to preserve the ditches and ditches, which were an indispensable part of the castle's defense system. Castles also functioned as administrative centers, and bodies of water helped facilitate tax collection, as rivers and seas were important trade waterways.

Castles were also built on high hills or in cliffs of rocks, which were difficult to attack.

Stages of the construction of the castle

At the beginning of the construction of the castle, ditches were dug in the ground around the location of the future building. Their contents folded inside. It turned out to be a mound or a hill called “mott”. On it later the castle was erected.

Then the walls of the castle were built. Often builders erected two rows of walls. The outer wall was lower than the inner. On it were towers for the defenders of the castle, drawbridge and airlock. Towers were built on the inner wall of the castle, which were used for living. The basement rooms of the towers were intended for storing food in the event of a siege. The area that was surrounded by the inner wall was called the Bailey. On the site was the tower where the feudal lord lived. Castles could be supplemented with annexes.

What locks were made of

The material from which the locks were made depended on the geology of the area. The first castles were built of wood, but later stone was used as a building material. In the construction used sand, limestone, granite.

All construction work was done manually.

Castle walls rarely consisted entirely of hard stone. Outside the wall, a lining was made of processed stones, and stones of an uneven shape and different sizes were laid out on its inner side. These two layers were combined using a lime mortar. The solution was prepared right at the site of the future construction, and with it stones were also whitened.

At the construction site, wooden forests were erected. At the same time, horizontal beams stuck into the holes made in the walls. Boards were laid above them across. On the walls of castles of the Middle Ages you can see square indentations. These are marks from scaffolding. At the end of construction, construction niches were filled with limestone, but over time it fell off.

The windows in the locks were narrow openings. On the castle tower, small openings were made so that the defenders could shoot arrows.

What did the locks cost?

If it was a royal residence, then specialists from all over the country were hired for the construction. So the king of medieval Wales, Edward the First, built his ring castles. Masons cut the stones into blocks of the correct shape and size, using a hammer, chisel and measuring tools. This work required high skill.

Stone castles were an expensive pleasure. King Edward almost ruined the state treasury, spending 100,000 pounds on their construction. About 3,000 workers were involved in the construction of one castle.

The construction of castles took three to ten years. Some of them were built in the war zone, and more time was required to complete the work. Most castles built by Edward One still stand.

At all times, people had to protect themselves and their property from the encroachments of their neighbors, and therefore the art of fortification, that is, the construction of fortifications, is very ancient. In Europe and Asia, one can see everywhere the fortresses built in antiquity and in the Middle Ages, as well as in the New and even Modern times. It might seem that the castle is just one of all the other fortifications, but in reality it is very different from the fortifications and fortresses that were built in previous and subsequent times. The large Celtic “dunes” of the Iron Age and the “campuses” of the ancient Romans, erected on the hills of Ireland and Scotland, were fortifications, the walls of which in case of war shelter the population and armies with all their property and cattle. The “burgs” of Saxon England and the Teutonic countries of continental Europe served the same purpose. Ethelfred, daughter of King Alfred the Great, built the Worcester burg for the "refuge of the whole people." The modern English words “borough” and “burg” come from this ancient Saxon word “burn” (Pittsburgh, Williamsburg, Edinburgh), as well as the names Rochester, Manchester, Lancaster come from the Latin word “castra”, which means “fortified camp” . These fortresses can in no way be likened to a castle; the castle was the private castle and home of the Lord and his family. In European society during the late Middle Ages (1000-1500), in a period that can rightfully be called the era of castles or the era of chivalry, the rulers of the country were lords. Naturally, the word "lord" is used only in England, and it comes from the Anglo-Saxon word hlaford. Hlaf - this is "bread", and the whole word means "distributing bread." That is, this word was used to refer to the good father-intercessor, and not a soldier with iron fists. In France, such a lord was called seigneur,in Spain senor,in Italy signormoreover, all these names are derived from the Latin word seniorwhich means "elder", in Germany and the Teutonic countries the lord was called Herr, Heeror Her.

The English language has always been distinguished by great originality in word formation, as we have already seen in the example of the word knight.The interpretation of the sovereign seigneur as a gentleman distributing bread was generally true for Saxon England. It must have been difficult and bitter for the Saxons to call this name the new powerful Norman lords who had begun to rule England since 1066. Exactly these lordsthe first large castles were built in England, and until the fourteenth century the Lords and their knightly retinue spoke exclusively in Norman-French. Until the thirteenth century they considered themselves French; most of them owned lands and castles in Normandy and Brittany, and the names of the new rulers themselves came from the names of French cities and villages. For example, Baliol - from Balley, Sachevrel - from Sot de Chevrei, as well as the names Beauchamp, Beaumont, Bure, Lesi, Claire and others.

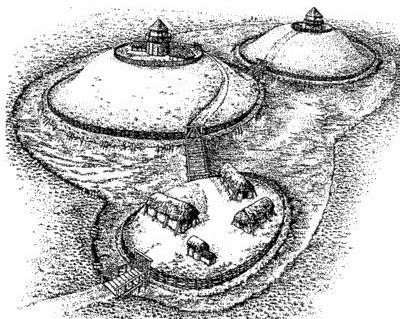

The castles that are so familiar to us today are not very similar to the castles that the Norman barons built for themselves, both in their own country and in England, since they were usually built of wood, not stone. There are several early stone castles (the large tower of the Tower of London is one of the surviving and almost unchanged examples of such architecture) built at the end of the 11th century, but the great era of the construction of stone castles began only around 1150. The fortifications of the early castles were earthen ramparts, the appearance of which has changed little in the two hundred years that have passed since the construction of such fortifications on the continent began. The world's first castles were built in the Frankish kingdom to protect against Viking raids. Castles of this type were earthworks — an oblong or rounded moat and an earthen rampart that surrounded a relatively small area, in the center or on the edge of which there was a high bulk hill. On top of the earthen rampart was crowned with a wooden picket fence. The same palisade was placed on the top of the hill. A wooden house was built inside the fence. Apart from the bulk hill, such buildings are very reminiscent of the houses of the pioneers of the American Wild West.

At first, this type of castle dominated. The main structure, ascended to an artificial hill, was later encircled by a moat and an earthen rampart with a picket fence. Inside the square, bounded by a rampart, was the courtyard of the castle. The main building, or the citadel, stood on top of an artificial, fairly high hill on four powerful corner posts, due to which it was raised above the ground. The following is a description of one of these castles, given in the biography of Bishop John of Teruenne, written about the year of the year: “Bishop John, traveling around his parish, often stayed in Merchem. Near the church there was a fortification, which with good reason can be called a castle. It was built according to the custom of the country by the former lord of this area many years ago. Here, where noble people spend most of their lives in wars, they have to defend their homes. To do this, pour a hill of land as high as possible, and surround it with a moat as wide and deep as possible. The top of the hill is surrounded by a very strong wall of hewn logs, placing small turrets around the hedge circumference - as much as the means allow. Inside the hedge they put a house or a large building, from where you can watch what is happening nearby. You can enter the fortress only through the bridge, which starts from the counter-escarp ditch, supported by two or even three supports. This bridge rises to the top of the hill. " Further, the biographer tells how once, when the bishop and his servants climbed the bridge, he collapsed, and people from a height of thirty-five feet (11 meters) fell into a deep ditch.

The height of the bulk hill was usually 30 to 40 feet (9-12 meters), although there were exceptions - for example, the height of the hill on which one of the Norfolk castles near Thetford was set reached hundreds of feet (about 30 meters). The top of the hill was made flat and the upper palisade surrounded the courtyard with an area of \u200b\u200b50-60 square yards. The vastness of the yard varied from one and a half to 3 acres (less than 2 hectares), but rarely was very large. The shape of the castle territory was different - some had an oblong shape, some had a square shape, there were courtyards in the form of a figure eight. Variations were very diverse depending on the magnitude of the state of the host and the configuration of the site. After the site for construction was selected, its first thing was dug in the moat. The excavated earth was thrown onto the inner bank of the moat, resulting in a rampart, an embankment called a scarp.The opposite bank of the moat was called, respectively, counterescarp. If this was possible, a ditch was dug up around a natural hill or other elevation. But as a rule, the hill had to be poured, which required a huge amount of earthwork.

Fig. 8. Reconstruction of the XI century castle with a mound and a courtyard. The courtyard, which in this case is a separate enclosed area, is surrounded by a palisade of thick logs and surrounded by a moat on all sides. The hill, or embankment, is surrounded by its own separate moat, and on the top of the hill around the tall wooden tower is another palisade. The citadel is connected to the courtyard through a long suspension bridge, the entrance to which is protected by two small towers. The upper part of the bridge is lifting. If the attacking enemy captured the yard, then the defenders of the castle could retreat along the bridge behind the palisade on the top of the bulk hill. The lifting part of the suspension bridge was very light, and those who retreated could simply drop it down and lock themselves behind the upper picket fence.

Such were the castles commonly erected in England after 1066. One of the tapestries, woven a bit later than the event depicted on it, shows how the people of Duke Wilhelm - or, more likely, the Saxon slaves gathered in the district - are building a mound of the castle in Hastings. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle for 1067 tells how "the Normans build castles throughout the country and oppress the poor people." The Doomsday Book has a record of houses that had to be demolished in order to build castles - for example, 116 houses were demolished in Lincoln and 113 in Norwich. It was such easily built fortifications that the Normans needed at that time in order to consolidate the victory and subjugate the hostile English, who could quickly gather strength and rebel. It is interesting to note that when a hundred years later the Anglo-Normans, led by Henry II, tried to conquer Ireland, they built exactly the same castles on the occupied lands, although in England and on the continent large stone castles have already replaced the old wood-earth fortifications with bulk hills and palisades.

Some of these stone castles were completely new and built in new places, while others were rebuilt old castles. Sometimes the main tower was replaced by a stone tower, leaving the wooden palisade surrounding the castle courtyard intact, in other cases, a stone wall was built around the castle courtyard, leaving the wooden tower untouched on the top of the bulk hill untouched. For example, in York, an old wooden tower stood two hundred years after a stone wall was erected around the courtyard, and only Henry III between 1245 and 1272 replaced the wooden main tower with a stone tower that has survived to this day. In some cases, new stone main towers were built on the tops of old hills, but this only happened when the old castle was built on a natural elevation. An artificial hill, poured just a hundred years ago, could not withstand the heavy weight of a stone building. In some cases, when the man-made hill was not enough donkey at the time of construction, the tower was erected around the hill, including it in a larger foundation, as, for example, in Kenilworth. In other cases, they did not build a new tower on the top of the hill, but instead replaced the old palisade with stone walls. Residential buildings, farm buildings, etc. were erected inside these walls. Such structures are now called fencing(shell keeps) - A typical example is the Round Tower of Windsor Castle. The same are well preserved in Restormell, Tamworth, Cardiff, Arundel and Carisbrooke. The outer walls of the courtyard supported the slopes of the hill, preventing them from creeping, and connected from all sides with the walls of the upper fence.

For England, the main buildings of castles in the form of towers are more characteristic. In the Middle Ages this building, this main part of the citadel was called a donjon or just a tower. The first word in English has changed its meaning, because nowadays, hearing the word “dungeon”, you do not imagine the main tower of the castle citadel, but a gloomy prison. And of course, the Tower of London Castle has retained its former historical name.

The main tower was the core, the most fortified part of the castle citadel. On the ground floor there were storage facilities for most of the food supplies, as well as an arsenal where weapons and military equipment were stored. Above there were premises for guards, kitchens and living quarters for the soldiers of the castle garrison, and on the upper floor the lord himself, his family and his retinue lived. The military role of the castle was purely defensive, since in this impregnable nest, behind incredibly strong and thick walls, even a small garrison could hold out as long as the supplies of food and water allowed. As we will see later, there were times when the main towers of the citadel were attacked by the enemy or damaged so that they became unsuitable for defense, but this rarely happened; usually locks were seized either as a result of treason, or the garrison surrendered, unable to bear the hunger. Problems with water supply rarely occurred, since there was always a source of water in the castle - one such source can still be seen today in the Tower of London.

Fig. 9. Pembroke castle; shows a large cylindrical dungeon built in 1200 by William Marshall.

Fencing was quite common, probably because it was the easiest way to rebuild the existing castle with a courtyard and a mound, but still the most typical feature of a medieval, and especially English, castle is a large quadrangular tower. It was the most massive building that was part of the castle buildings. The walls were distinguished by gigantic thickness and were installed on a powerful base capable of withstanding the blows of picks, drills and stenobite guns besieging. The height of the walls from the base to the toothed top averaged 70-80 feet (20-25 meters). Flat buttresses, called pilasters, supported the walls along their entire length and in the corners; at each corner, such a pilaster was crowned with a turret on top. The entrance was always located on the second floor, high above the ground. An external staircase led to the entrance, located at right angles to the door and covered by a pylon tower installed directly outside the wall. For obvious reasons, the windows were very small. On the first floor there were none at all, on the second they were tiny and only on the next floors did they become a little larger. These distinguishing features - a walk-in tower, an external staircase and small windows - can be clearly seen in Rochester Castle and Headingham Castle in Essex.

The walls were made of rough stones or gravel lined with ashlar inside and out. These stones were worked well, although in rarer cases the external cladding was also made of uncut stones, for example, in the White Tower of London. In Dover, the castle built by Henry II in 1170, the walls are 21-24 feet (6-7 meters) thick; in Rochester, their thickness reaches 12 feet (3.7 meters) at the base, gradually decreasing to the roof to 10 feet (3 meters). The upper, non-endangered parts of the walls were usually slightly thinner - their thickness decreased on each next floor, allowing a little gain in space, reduce the weight of the building and save building material. In the towers of such large castles as London, Rochester, Colchester, Headingham and Dover, the internal volume of the building was divided in half by a thick transverse wall that went through the entire structure from top to bottom. The upper parts of this wall were lightened by numerous arches. Such transverse walls increased the strength of the building and facilitated the laying of floors and roofing, as they reduced the spans that had to be blocked. In addition, the transverse walls were advantageous in a purely military sense. For example, in Rochester in 1215, when King John besieged the castle, his sappers led a dig under the northwest corner of the main tower, and it collapsed, but the defenders of the castle moved to the other half, separated by a transverse wall, and held out for some time.

The more massive and higher main towers were divided into a basement and three upper floors; in the smaller castles on the basement two floors were erected, although there are, of course, exceptions. For example, in Korf Castle - very high - there were only two upper floors, just like in Guildford, but in Norham Castle there were four upper floors. In some castles, such as Kenilworth, Rising, and Middleham — all of them looked elongated in plan and not particularly high — there was only a basement and one upper floor.

Fig. 10. The main tower of the Rochester Castle, Kent. Built in 1165 by King Henry II, this castle, besieged in 1214 by King John, was taken after a dig was brought under the north-western corner tower. The modern round turret was completed to replace the collapsed Henry III (the original text says that this happened in 1200, which is impossible, since Henry was born in 1207. - Per.). On the right in the figure, a bridge tower is visible.

Each floor was one large room, divided in two, if the castle had a transverse wall. The basement was used as a pantry: there they stored provisions for the garrison and fodder for horses, food for servants, as well as weapons and various military equipment, among other things, necessary for ensuring the vital functions of the castle in peacetime and wartime, - stones and wood for repair, paints, lubricants, leathers, ropes, bales of fabrics and linens, and probably reserves of quicklime and combustible oil that were poured onto the heads of the besiegers. Often the upper floor was divided by wooden walls into smaller rooms, and in some castles, such as Dover or Hedgingam, the main room - the hall of the second floor - was made double-light; the hall turned out to be a very high arch, and galleries ran along the walls. (The main tower of the castle in Norwich, where the museum is now located, is designed in this way and allows you to understand how it looked in real life.) Fireplaces were installed in the larger main towers on the upper floors, many of which were preserved to this day.

Fig. 11. The main building of the Headingham Castle in Essex, built in 1100. On the left side of the figure, a staircase leading to the front door is visible. Initially, as in Rochester, this staircase was covered by a tower.

Stairs leading to all floors of the main building were arranged in its corners, they led from the basement to the turrets and went onto the roof. The stairs were twisted clockwise. This direction was not chosen by chance, since the defenders of the castle had to fight on the stairs if the enemy broke into the castle. In this case, the defenders had the advantage: of course, they tried to push the enemy down, while the left hand with the shield rested on the central pole of the stairs, and for the right hand, which acted as a weapon, there was enough space even on a narrow staircase. The attackers were forced, overcoming the resistance, to make their way up, while their weapons constantly ran into the central pillar. Try to imagine this situation, being on a spiral staircase, and you will understand what I mean.

Fig. 12. The main hall of the Headingham Castle in Essex. The arch, which stretches from left to right in the figure, represents the upper part of the transverse wall, dividing the volume of the castle into two halves. The transverse wall, which is very thick in the basement, turns into an arch in the upper floor, which helps to lighten the weight of the building and make the main hall more spacious.

In the upper floors of the main building, many small rooms were arranged directly in the wall. These were private rooms, rooms in which the lord of the castle, his family and guests slept; latrines were also located in the thickness of the walls. Toilets are very elaborate; medieval notions of sanitation and hygiene are not as primitive as we tend to think. The latrines of medieval castles are more comfortable than the needles that are still found in rural areas, and besides, they were easier to keep clean. Toilets were small rooms that protruded beyond the outer wall. The chairs were made of wood, they were above the hole that opened out. All, so to speak, waste, like on trains, spilled directly onto the street. Lavatories in those days were evasively called wardrobes (translated from French, “wardrobe” literally means “take care of the dress”). In Elizabethan times, the euphemism for the word restroom was the word “jake”, just as we in America call the restroom “john”, and the English use the word “lu” for the same purpose.

The source or spring was extremely important for the survival of the inhabitants and defenders of the castle. Sometimes, as it was in the Tower, the source was in the basement, but more often it was brought to the living quarters - it was more reliable and convenient. Another detail of the castle, which at that time was considered absolutely necessary, was the house church or chapel, which was located in the tower in case the defenders were cut off from the yard, if it was captured by the enemy. An excellent example of the chapel is located in the main tower of the White Tower of London, but still more often the chapels were located in the upper part of the porch that covered the front door.

At the end of the 12th century, important changes were planned in the architecture of the main tower of the castle. Rectangular in terms of the tower, despite the fact that they were very massive, had one significant drawback - sharp corners. The enemy, while remaining virtually invisible and inaccessible (you could shoot only from the turret located at the top of the corner), could methodically remove stones from the wall, destroying the castle. In order to end this inconvenience and reduce the risk, they began to build round towers, such as the main tower of the Pembroke Castle, built in 1200 by William Marshall. Some towers had an intermediate, transitional view, so to speak, a compromise between the old rectangular structure and the new cylindrical. These were polygonal towers with oblique oblique corners. Examples include Orford Castle Towers in Suffolk and Konisboro in Yorkshire, the first was built by King Henry II between 1165 and 1173, and the second by Count Gamlin de Weyrenne in the 90s of the 12th century.

The stone walls that replaced the old palisades around the castle courtyards were built on the basis of the same military engineering considerations as the main towers. The walls were built as high and as thick as possible. The lower part was usually wider than the upper one to provide strength to the most vulnerable part of the wall, as well as to make the wall surface sloping so that stones and other throwing weapons dropped from above would bounce off the bottom, ricochet and hit the besieging enemy more strongly. The wall was notched, that is, it was crowned with structural elements, which we now call loopholes located between the battlements. Such a wall with loopholes was arranged as follows: on the top of the wall stretched a fairly wide passage or platform, which in Latin was called alatorium,from which the English word came allure- wall balustrade. On the outside, the balustrade was protected by an additional wall from 7 to 8 feet high (about 2.5 meters), interrupted at equal distances by transverse slit-like openings and openings. These openings were called embrasures, and the sections of the parapet between them - merlonsor cogs. The apertures allowed the defenders of the castle to shoot at the attackers or drop various projectile shells at them. True, for this, the defenders had to show themselves to the enemy for some time before again hiding behind the prong. To reduce the risk of injury, narrow slots were often made in the teeth, through which the defenders could shoot from bows, while being in the shelter. These slots were located vertically in the wall or in the tooth, had a width of no more than 2-3 inches (5-8 centimeters) from the outside, and from the inside were wider so that the arrow was more convenient to manipulate the weapon. Such rifle slots had a height of up to 6 feet (2 meters) and were provided with an additional transverse slit just above half the height of the slit. These transverse slots were designed so that the shooter could throw arrows in the lateral directions at an angle of up to forty-five degrees to the wall. There were many designs of such slots, but in fact they were all the same. One can imagine how difficult it was for an archer or arbalester to get an arrow into such a narrow gap; but if you visit a castle and stand at a rifle slit, then make sure how clearly the battlefield is visible, what a great view the defenders had and how convenient it was to shoot through these slots with a bow or crossbow.

Fig. 13. Reconstruction of the flank tower and the walls of the castle courtyard of the XIII century. The tower has a cylindrical shape on the outside and flat inside. On the inner side of the tower it is seen that a small lift is sticking out of the wall, with the help of which ammunition was delivered to the defenders who were behind the fence inside the platform on the tower. The high roof is made of thick wooden rafters, tiled, flat stones or slate. The crown of the tower under the roof is surrounded by a wooden fence. One can imagine that the attackers, having overcome the moat filled with water, fell under the fire of archers who were in the tower at its top and behind the gallery fence. A pedestrian area at the top of the wall is shown, as well as buildings adjacent to the wall in the courtyard of the castle.

Of course, there are a lot of shortcomings in the wall surrounding the castle, since if the attackers got to its foot, they became inaccessible to the defenders. Anyone who dares to lean out of the embrasure will be shot dead immediately, while one who would remain under the protection of the battlements could not do any harm to the attackers. Therefore, the best solution was to dismember the wall and build along its perimeter at equal intervals guard towers or bastions that protruded forward, beyond the plane of the wall in the field, and through the shooting gaps in their walls, the defenders were able to shoot from loopholes in all directions, that is, shooting the enemy in the longitudinal direction, along the enfilade, as expressed in those days. At first, such towers were rectangular, but then they began to be erected in the form of half-cylinders protruding from the outside of the walls, while the inner side of the bastion was flat and did not protrude beyond the plane of the wall of the castle courtyard. The bastions rose above the upper edge of the wall, dividing the pedestrian parapet into sectors. The path continued through the tower, but if necessary, it could be blocked by a massive wooden door. Therefore, if some detachment of attackers managed to penetrate the wall, then it could be cut off in a limited area of \u200b\u200bthe wall and destroyed.

Fig. 14. Various types of shooting slots. In many castles in their various parts rifle slots of various shapes were located. Most of the slots had an additional transverse slot, which allowed the archer to shoot not only directly in front of him, but also in the lateral directions at an acute angle to the wall. However, such cracks were made that did not have a transverse part. The height of rifle slits ranged from 1.2 to 2.1 meters.

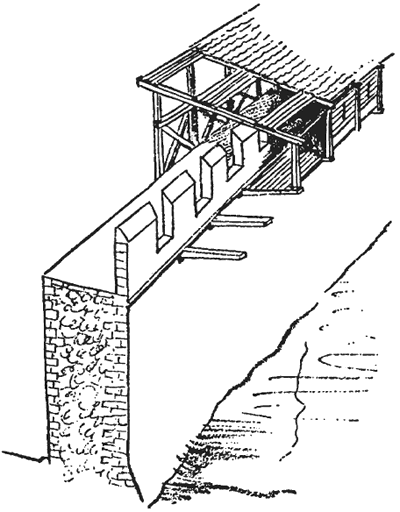

The castles that can be seen today in England usually have a flat top and are not covered with a roof. The upper edge of the walls is also flat, except for the teeth, but in those days when the castles were used for their intended purpose, the main towers and bastions often had a steep roof, which today can be seen in castles of continental Europe. We tend to forget, looking at such dilapidated castles as Usk in Dover or Konisboro, which could not resist the onslaught of inexorable time, with which they were covered with wooden roofs. Very often, the upper part - parapets and footpaths - of walls, bastions and even the main towers was crowned with long wooden covered galleries, called fences, or in English hoarding(from the Latin word hurdicia),or sail. These galleries protruded about 6 feet (about 2 meters) beyond the outer edge of the wall, holes were made in the floor of the galleries, allowing them to shoot through the attackers at the foot of the wall, throw stones at the attackers and pour boiling oil or boiling water on their heads. The disadvantage of such wooden galleries was their fragility - these structures could be destroyed with the help of siege machines or set on fire.

Fig. 15. The diagram shows how fences, or “jumpers,” were attached to the walls of the castle. They were probably only set up when the castle was threatened by a siege. In many walls of castle courtyards, you can still see square holes in the walls under the battlements. Beams were inserted into these holes, on which a fence with a covered gallery was placed.

The gate was the most vulnerable part of the wall surrounding the castle courtyard, and at first, close attention was paid to the gate defense. The earliest way to protect the gate was to place it between two rectangular towers. A good example of this type of protection is the device of the gate in the Exeter castle of the XI century that has survived to this day. In the XIII century, square gate towers give way to the main gate tower, which is a merger of two former with additional floors built on top of them. These are the gate towers in the castles of Richmond and Ludlow. In the XII century, the more common way to protect the gate was the construction of two towers on both sides of the entrance to the castle, and only in the XIII century appear gate towers in their finished form. The two flanking towers are now combined into one over the gate, becoming a massive and powerful fortification and one of the most important parts of the castle. The gate and entrance will now turn into a long and narrow passage blocked at each end porticules.These were flaps vertically sliding along the gutters cut in stone, made in the form of large gratings made of thick timber, the lower ends of the vertical bars were pointed and bound by iron, thus the lower edge porticulesit was a series of pointed iron stakes. Such lattice gates were opened and closed with thick ropes and a winch located in a special chamber in the wall above the passage. In the "bloody tower" of the Tower of London, you can still see porticowith operating hoist. Later, the entrance began to be protected with the help of the "mercury", deadly holes drilled in the vaulted ceiling of the passage. Through these openings, for everyone who tried to force their way to the gates, objects and substances that were usual in such a situation were streaming and pouring - arrows, stones, boiling water and hot oil. However, another explanation seems more plausible - water was poured through the holes if the enemy tried to set fire to the wooden gate, since the best way to get into the castle was to fill the passage with straw, logs, thoroughly soak the mixture with combustible oil and set fire to it; two birds with one stone were killed at once - the trellised gates were burned and the defenders of the castle were fried in the gate rooms. Within the walls of the aisle were small rooms equipped with rifle slits through which the defenders of the castle could strike from the bows a close mass of attackers who sought to break into the castle.

In the upper floors of the gate tower there were rooms for soldiers and often even living quarters. In special chambers there were gates, with the help of which the drawbridge was lowered and raised on chains. Since the gate was the place that was most often attacked by the enemy besieging the castle, they were sometimes provided with another means of additional protection - the so-called barbicans, which began at a certain distance from the gate. Usually the barbican consisted of two high thick walls running parallel to the outside of the gate, forcing the enemy, thus, squeezing into the narrow passage between the walls, substituting under the arrows of the archers of the gate tower and the upper platform of the barbican hidden behind the battlements. Sometimes, to make access to the gates even more dangerous, a barbican was installed at an angle to them, which forced the attackers to go to the gates on the right, and parts of the body that were not covered by shields turned out to be targets for archers. The entrance and exit of the barbican was usually quite fancifully decorated. In Goodrich Castle near Gerfordshire, for example, the entrance is in the form of a semicircular vault, and the two barbicans covering the gates of Conway Castle looked like small castle courtyards.

Fig. 16. Reconstruction of the gate and barbican of the castle of Arc in France. The Barbican is a complex structure with two drawbridges, covering the main entrance.

The gatehouse, built in the middle of the 14th century by Thomas Beauchamp, Earl of Warwick (grandfather of Count Richard), is a good example of a compact watchtower and a barbican connected in a beautifully designed ensemble. The gate tower is built in the traditional plan in the form of two towers, connecting above the narrow passage, it has three additional floors with tall battlements at each corner, towering above the battlements of the walls. In front, outside the castle, two battlements form another narrow passage leading to the castle; at the far end of these walls of the barbican, beyond their limits, there are two more towers - smaller copies of the gate tower. In front of them is a drawbridge over a moat filled with water. This means that the attackers, in order to break through to the gate, first had to make their way through the raised drawbridge with a sword or sword, blocking the path to the first gate and the portico located behind them. Then they would have to break through the narrow passage of the Barbican with battle. After that, finally facing the gates themselves, the attackers would be forced to force a second moat, break through the next raised bridge and porticules. Having accomplished these exploits, the enemy found himself in a narrow corridor, showered with arrows and doused with boiling water and hot oil from numerous mortars and rifle slots in the side walls, and at the end of the enemy’s path the following porticules waited. But the most interesting way in the construction of this gate tower was the truly scientific method by which the battlements located on the steps covered each other. At first there were walls and turrets of the Barbican, behind them and above them there were walls and the roof of the gate tower, over which the corner turrets of the gate tower dominated, the first pair was located below the second, from each subsequent shooting range it was possible to cover the underlying one. The towers of the gateway were connected by transitional hanging arched stone bridges, so the defenders did not have to go down to the roof to move from one turret to another.

Today, when you enter the gate leading to the courtyard and the main tower of a castle such as Warwick, Dover, Kenilworth or Corf, you cross a large area of \u200b\u200bmowed grass in the courtyard. But everything here was different in those days when the castle was used for its intended purpose! The entire space of the courtyard was filled with buildings - mostly wooden, but there were stone houses among them. Numerous covered premises were located against the walls of the courtyard - some stood next to the wall, some were arranged directly in its thickness; there were stables, kennels, cowsheds, all kinds of workshops - masons, carpenters, gunsmiths, blacksmiths (you should not confuse a gunsmith with a blacksmith - the first was a highly skilled specialist), sheds for storing straw and hay, the dwellings of an army of servants and engravers, open kitchens, dining rooms , stone rooms for hunting falcons, a chapel and a large hall - more extensive and roomy than in the main tower of the castle. This hall, located in the courtyard, was used during the days of peace. Instead of grass, there was densely packed land or paved with cobblestones or even paving stones, or, in very few castles, the yard was covered with a mash of impassable dirt. Instead of tourists idly resting in the shade of the ruins, people who were busy with their daily work constantly walked here. Cooking took place almost continuously, horses were fed, watered and trained all the time, cattle was driven into the yard for milking and driven out of the castle into the pasture, gunsmiths and blacksmiths repaired the armor for the owner and soldiers of the garrison, shoe horses, forged iron objects for the needs of the castle , repaired carts and carts - there was an incessant noise of continuous operation.

Fig. 17. The figure shows one way of constructing a drawbridge.